At the Edge of the Pacific: A Genetic Time Capsule

In the tropical lowlands and offshore islands of Papua New Guinea (PNG), genetic echoes of ancient voyages still course through living communities. Now, researchers have retrieved and analyzed the ancient genomes of 42 individuals from these coastal regions and the nearby Bismarck Archipelago, offering a detailed view into 2,500 years of human interaction, mobility, and adaptation. The results paint a portrait of surprising continuity—and surprising delay—in one of the most culturally diverse regions on Earth.

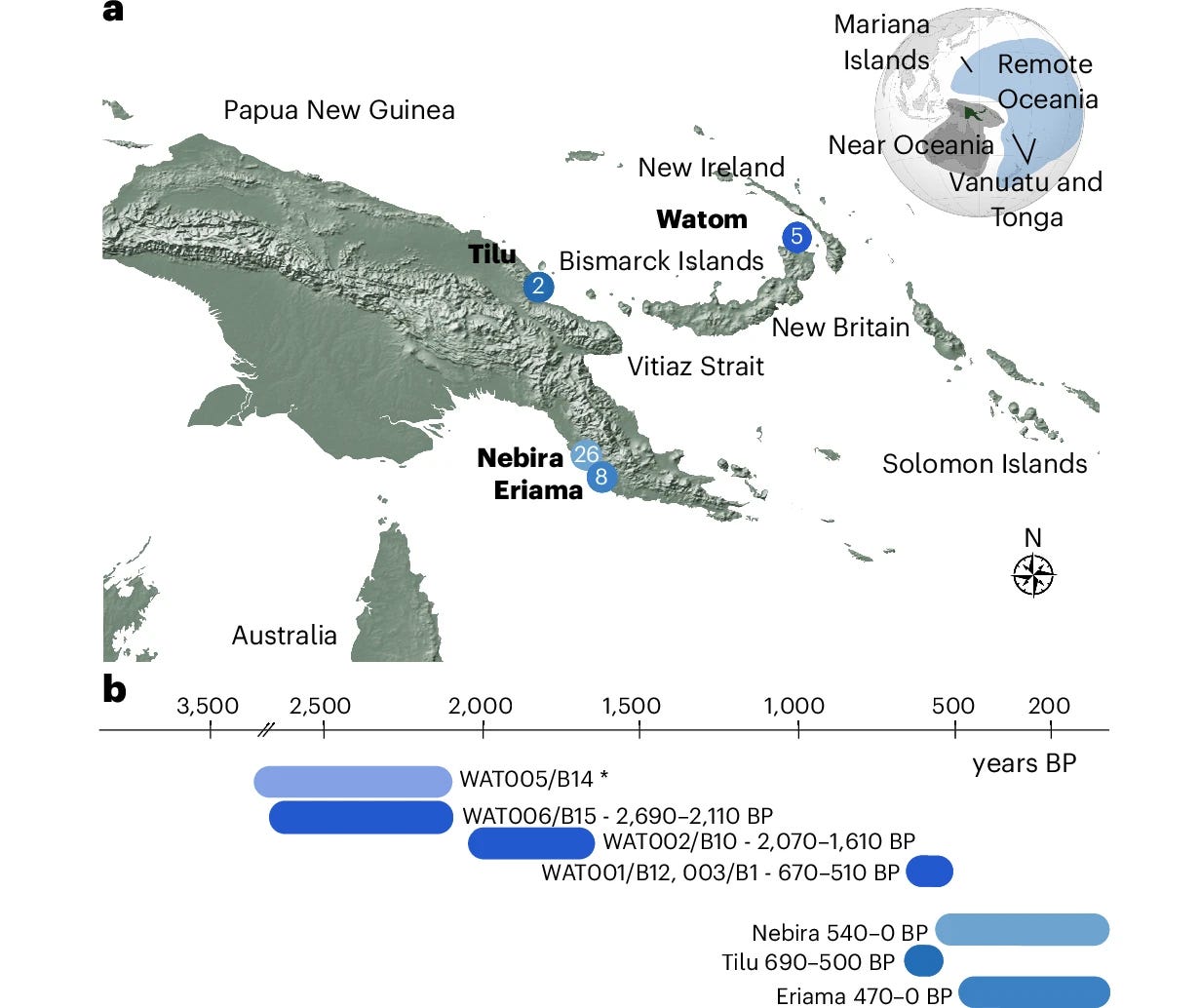

The study, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution1, draws on genome-wide data, radiocarbon dating, stable isotope analysis, and dental calculus to reconstruct a complex demographic and dietary past. At its core lies a central puzzle: how and when did incoming populations—particularly Austronesian-speaking peoples from East Asia—interact and intermix with the indigenous Papuan populations of Near Oceania?

Lapita Pottery, But Not Immediate Mixing

The Lapita cultural complex, with its distinctive dentate-stamped pottery and reputation for long-distance seafaring, arrived in the Bismarck Archipelago around 3,300 years ago. But the ancient DNA from Watom Island—an early Lapita site—reveals that genetic intermingling with Papuan groups didn’t happen right away.

"Two individuals from Watom dating to the middle to late Lapita period carried only Papuan-related ancestry," the study reports. "Their genomes lacked any signs of East Asian admixture despite their burial in a Lapita-associated site."

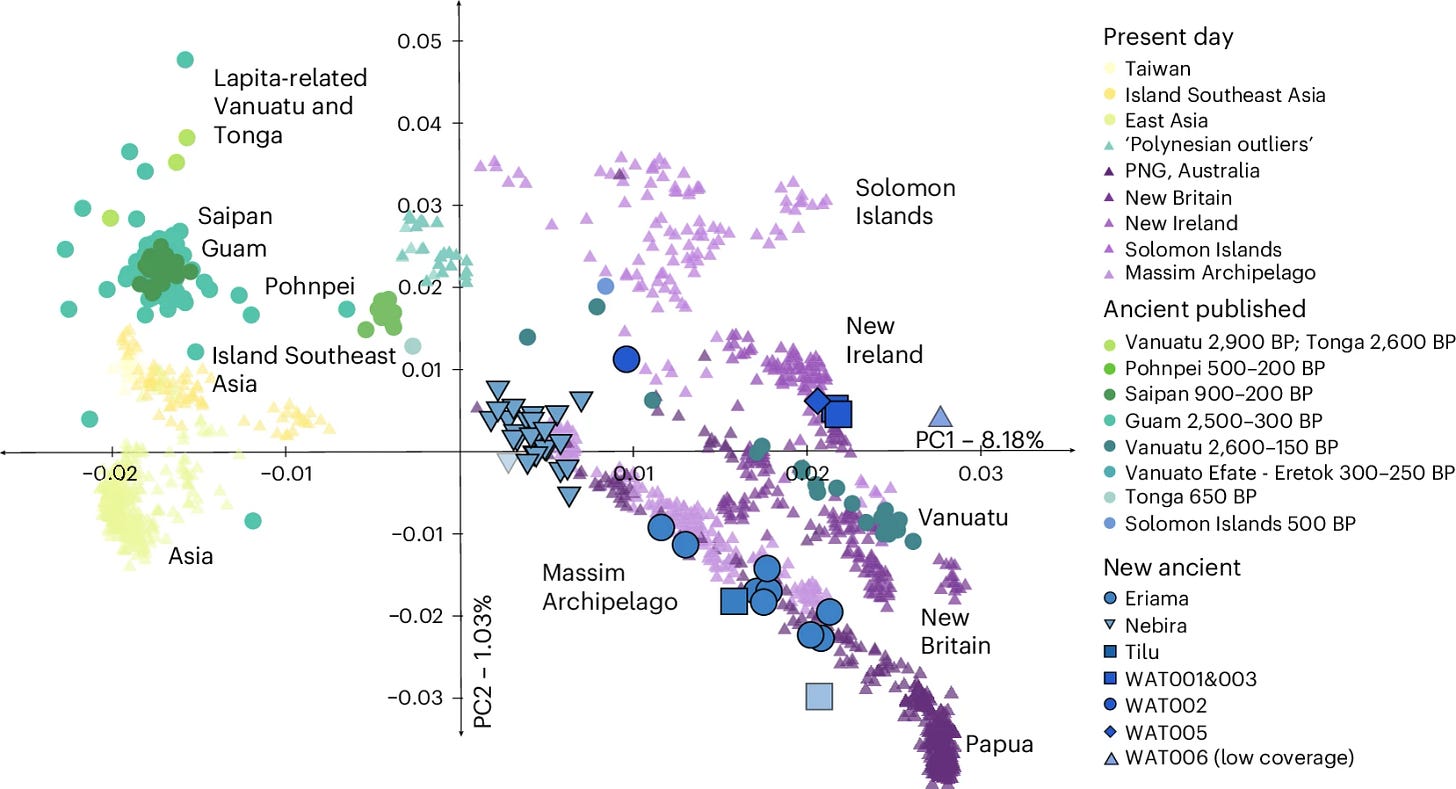

It wasn't until nearly 2,000 years ago that researchers found clear genetic evidence of mixing between East Asian and Papuan ancestries in the region. This admixture appears to have occurred centuries after the first Lapita settlers arrived. In one Watom individual dated to around 1,900 BP, roughly 40% of her ancestry came from East Asian-related populations.

This delayed genetic integration raises important questions. Why did these groups share cultural artifacts but not immediately intermarry? The evidence suggests extended periods of parallel occupation, perhaps even segregation, before more intimate forms of cultural integration began.

Coastal Communities, Divergent Histories

The story deepens on the south coast of mainland New Guinea, where the sites of Nebira and Eriama lie just a few kilometers apart. Yet the genomes of individuals from these sites tell strikingly different stories.

At Nebira, individuals carry a higher proportion of East Asian ancestry (45–60%) with admixture dates averaging around 1,500 years ago. Eriama’s individuals, on the other hand, show lower East Asian ancestry (~20%) and more recent mixing.

"Despite close proximity, these two communities appear to have diverged around 650 years ago," said the researchers. "This is evidenced not only by their genetic makeup but also their distinct burial practices and dietary signatures."

One group buried their dead in caves; the other in formal cemeteries. One consumed more marine foods; the other relied heavily on horticultural staples and wallaby meat. The fine-grained strontium isotope data even show that some individuals moved between inland and coastal zones during their lives.

Cultural Drift, Environmental Shocks

The divergence between communities also coincides with a poorly understood episode known to archaeologists as the "Papuan Hiccup" or "Ceramic Hiccup" — a period between 1,200 and 500 years ago characterized by the abandonment of coastal sites, interruptions in pottery production, and possibly climate instability linked to shifts in El Niño activity.

During this time, long-distance trade waned and settlement patterns shifted. Some groups relocated inland, others adopted more defensive, hilltop settlements. As one analysis notes, "the interruption of long-distance trade links might have led to abandonment of many long-term settlements and possibly sparked local conflict."

Despite these upheavals, genetic traces suggest continued interaction between neighboring groups. Individuals from Eriama and Nebira shared distant genetic ties, even as their social spheres diverged.

The Seafaring Past in Genomic Memory

Austronesian-speaking groups left a significant mark on the genetic landscape of coastal PNG. However, this influence was uneven, delayed, and mediated through complex local dynamics. While mitochondrial DNA reveals predominantly East Asian maternal ancestry, Y-chromosome data point to mostly Papuan paternal lineages—a pattern suggesting sex-biased admixture.

"We observe an excess of Austronesian-related ancestry on the X chromosome, ranging from 10 to 60 percentage points," the authors noted, "which likely reflects social structures in which Austronesian women married into Papuan communities."

Such patterns align with previous findings from Vanuatu, Wallacea, and Tonga, reinforcing a broader regional trend.Sailing Against the Wind: Who Reached the Marianas?

The researchers also addressed a separate but related question: how were the Mariana Islands first settled? Genomic comparisons suggest that these remote Pacific islands were most likely colonized from island Southeast Asia rather than from Near Oceania. One key line of evidence comes from a single individual on Watom Island whose genome split earlier than Lapita-associated genomes, matching ancient genomes from Guam and Saipan more closely.

This route would have required sailing against prevailing winds and currents—a feat of navigation that underlines the extraordinary maritime skill of the first Pacific voyagers.

Genetic Time Capsules in a Fragile Landscape

Despite its complexity, the genetic story told here is incomplete. Preservation in tropical PNG is notoriously poor, making these 42 ancient genomes all the more valuable. They hint at deep histories of encounter, resilience, and transformation in a place where oral traditions, language diversity, and archaeological richness converge.

The study's principal investigator summarized the stakes:

"These findings highlight that coastal Papua New Guinea was never a uniform frontier. It was, and remains, a mosaic of cultures shaped by seafaring, environmental flux, and enduring local traditions."

Related Research

Lipson, M., et al. (2018). "Ancient genomes document multiple waves of migration in Southeast Asian prehistory." Science, 361(6397), 92–95. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat3188

Skoglund, P., et al. (2016). "Genomic insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific." Nature, 538(7626), 510–513. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19844

Posth, C., et al. (2021). "Ancient DNA reveals multiple waves of migration in Micronesia." Nature Communications, 12(1), 4385. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24543-0

Nägele, K., Kinaston, R., Gaffney, D., Walworth, M., Rohrlach, A. B., Carlhoff, S., Huang, Y., Ringbauer, H., Bertolini, E., Tromp, M., Radzeviciute, R., Petchey, F., Anson, D., Petchey, P., Stirling, C., Reid, M., Barr, D., Shaw, B., Summerhayes, G., … Krause, J. (2025). The impact of human dispersals and local interactions on the genetic diversity of coastal Papua New Guinea over the past 2,500 years. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02710-x