The Mouth as Archive

Teeth endure. Long after flesh gives way to soil and bone to dust, teeth can linger with secrets locked in their plaque. At the site of Nong Ratchawat in central Thailand, one Bronze Age woman carried a story in her mouth—one not visible to the eye, not etched in grave goods or burned into pottery, but sealed in the hardened calculus on her molars.

When researchers analyzed her dental plaque, they detected molecules associated with betel nut chewing: arecoline and arecaidine, alkaloids with potent psychoactive effects. Their presence in a 4,000-year-old burial marks the earliest direct evidence of betel nut use in Southeast Asia.

This discovery, published in Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology1 by Piyawit Moonkham and colleagues, offers not only a timestamp for a millennia-old practice but a methodology that might change how archaeologists understand ancient plant use.

“This is the earliest direct biomolecular evidence of betel nut use in Southeast Asia,” the authors write.

Nong Ratchawat and Its Quiet Burials

Nong Ratchawat isn’t a site typically associated with grand finds. Situated in Suphan Buri Province, it has yielded more than 150 burials since excavations began in 2003. Grave goods are modest: beads, ceramic vessels, the occasional stone tool. But what these burials lack in spectacle, they make up for in potential.

For this study, six individuals were sampled, but only one—Burial 11—told a molecular story. In three calculus samples taken from a single molar, researchers found chemical signatures of Areca catechu, the betel nut palm. These compounds did not leach in from the environment. They were chewed, metabolized, and slowly integrated into the mineralizing plaque over time.

The woman in Burial 11 may not have stood out in life or death. Her tomb contained a few stone beads, but nothing that suggested elevated social standing. Still, her dental chemistry suggests regular consumption of a psychoactive substance—one deeply embedded in Southeast Asian ritual and social life for millennia.

Making the Invisible Traceable

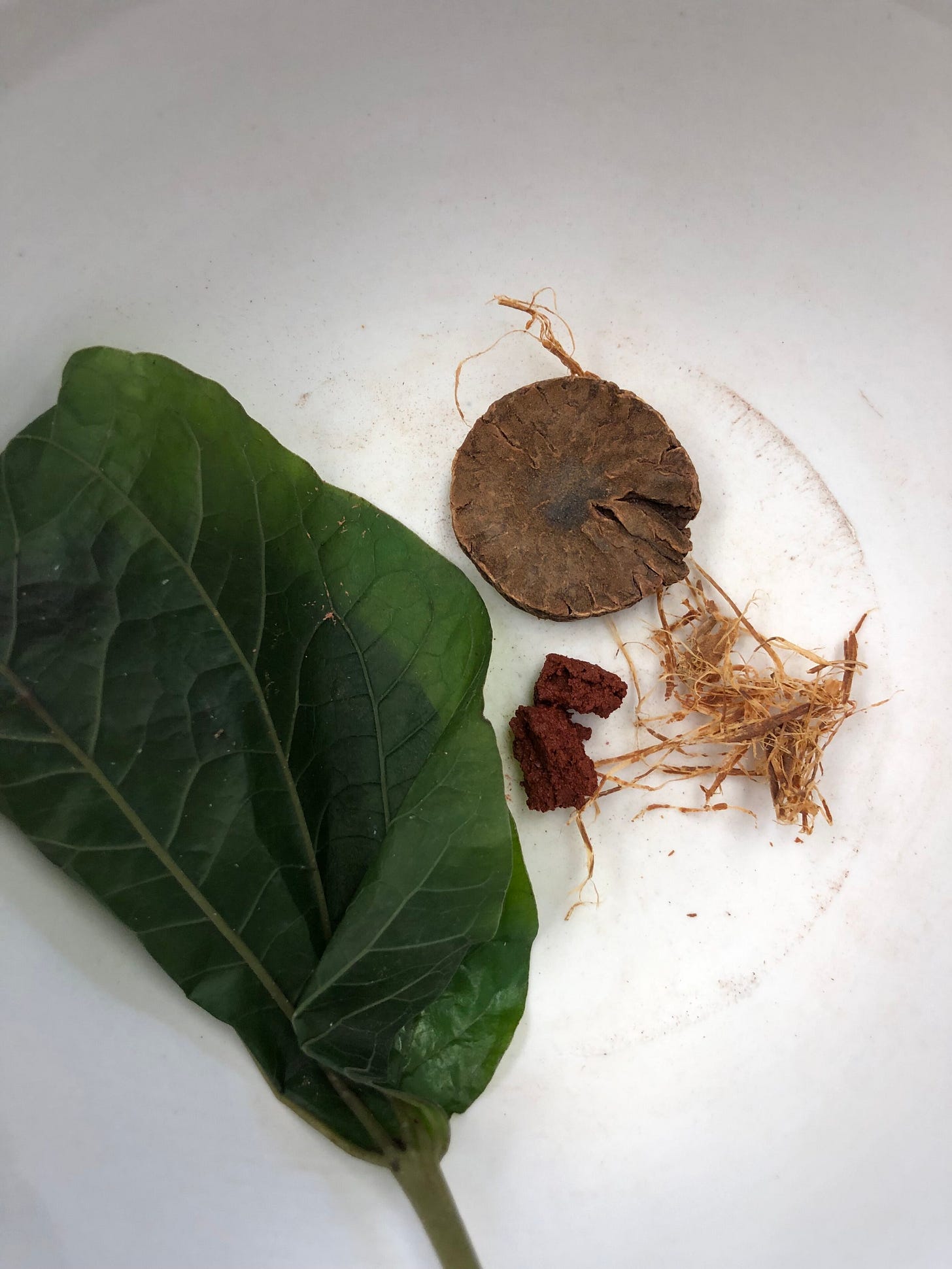

The team didn’t rely on guesswork. To validate their findings, they recreated Bronze Age chewing practices in the lab. Using dried betel nut, Piper betle leaves, pink limestone paste, Senegalia catechu bark, and human saliva, they produced traditional quids. These were analyzed to generate a reference dataset.

“We used dried betel nut, pink limestone paste, Piper leaves, and sometimes Senegalia catechu bark and tobacco. We ground the ingredients with human saliva to replicate authentic chewing conditions,” the authors explain.

This controlled experiment ensured that the chemical traces in ancient plaque could be meaningfully interpreted. The target compounds—arecoline and arecaidine—are alkaloids known to enhance alertness and induce euphoria. Their persistence in the fossilized mouth plaque confirms a practice that had, until now, remained invisible in the archaeological record.

Culture, Not Just Chemistry

Tooth staining is a hallmark of betel nut chewing today. It’s a visible badge of participation in a long-standing social ritual. Yet the woman in Burial 11 didn’t have stained teeth. That absence, researchers argue, shouldn’t be taken as absence of practice.

The lack of staining might result from different preparation methods, cleaning habits, or postmortem changes. The key insight is that visual inspection alone cannot reliably document psychoactive plant use in ancient populations.

“Dental calculus analysis can reveal behaviors that leave no traditional archaeological traces,” the study notes.

In this sense, plaque becomes a chemical diary—a personalized record of ingestion and habit. It offers evidence not just of diet or disease, but of mood, ritual, and the many ways people interacted with their botanical world.

Rethinking Intangible Heritage

The results invite broader reflection. For years, archaeobotanists have relied on macroremains: seeds, residues, charred fragments. These are crucial but limited. Practices like betel nut chewing often leave no such signature. Their tools biodegrade. Their byproducts vanish.

But teeth endure.

By refining methods for extracting and analyzing dental calculus, archaeologists can now revisit old burials with new questions. What was chewed, smoked, swallowed, or brewed? Who had access to intoxicants? Were they tied to gender, status, or community role?

“Understanding the cultural context of traditional plant use is a larger theme we want to amplify—psychoactive, medicinal, and ceremonial plants are often dismissed as drugs, but they represent millennia of cultural knowledge, spiritual practice, and community identity,” Moonkham emphasizes.

The Betel Trail Across Millennia

Betel chewing isn’t new to scholarship. It’s been documented across South and Southeast Asia, Oceania, and into the western Pacific. The cultural dimensions are vast: used to welcome guests, consecrate marriages, soothe nerves, or simply pass the time.

But direct archaeological evidence—especially chemical confirmation from ancient individuals—has been scarce.

This study shifts that landscape. It also opens new doors for understanding similar psychoactive traditions in contexts where residue is ephemeral. It asks scholars to rethink what can be preserved and how.

Further Reading and Related Studies

Tushingham, S., et al. (2018). Biomolecular archaeology of ancient plant use: New insights from dental calculus. Journal of Archaeological Science, 96, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2018.05.002

Dudgeon, J. V., & Tromp, M. (2014). Diet, microfossils and dental calculus: A new study of agricultural transition in prehistoric Guam. Journal of Archaeological Science, 49, 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.05.016

Radini, A., et al. (2019). Medieval women's early involvement in manuscript production suggested by lapis lazuli identification in dental calculus. Science Advances, 5(1), eaau7126. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau7126

Warinner, C., et al. (2015). Pathogens and host immunity in the ancient human oral cavity. Nature Genetics, 46, 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2906

Robinson, D., et al. (2023). Psychoactive plant use in prehistoric Oceania: Evidence from chemical residues and traditional knowledge. Antiquity, 97(392), 1155–1172. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2023.50

Moonkham, P., Tushingham, S., Zimmermann, M., Brownstein, K. J., Devanwaropakorn, C., Duangsakul, S., & Gang, D. R. (2025). Earliest direct evidence of bronze age betel nut use: biomolecular analysis of dental calculus from Nong Ratchawat, Thailand. Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, 4(1622935). https://doi.org/10.3389/fearc.2025.1622935