In the late second millennium BCE, the landscape of what is now northern Germany was dotted with monumental burial mounds. Among the largest and most elaborate are those at Seddin, in the Prignitz region of Brandenburg. Archaeologists have long noted that the artifacts buried here—razor-thin gold ornaments, fine bronze vessels, and exotic glass beads—hint at a community plugged into far-reaching networks of exchange. New isotope analysis1 of cremated human remains adds an even more striking layer: many of the dead themselves were born far from the sandy soils in which they were buried.

“Most buried individuals show a non-local, foreign strontium signature,” said Professor Kristian Kristiansen of the University of Gothenburg. “This aligns with archaeological evidence of intensified trade between these regions.”

An Elite Hub of the Late Bronze Age

Between 900 and 700 BCE, Seddin’s monumental mounds marked more than just local power. They were nodes in an interconnected world stretching from southern Scandinavia to northern Italy. The recent study, led by Dr. Anja Frank, is the first bioarchaeological investigation of Seddin’s elite burials. It shows that mobility was not limited to goods; it included people of high status.

“We were able to identify that their chemical composition was foreign to the region,” Dr. Frank explained. “However, the investigated individuals generally came from outstanding burial mounds, meaning our results represent only the elites.”

The findings emerge from the analysis of cremated remains—bones reduced to fragments but still chemically resilient. In particular, the researchers targeted the petrous portion of the temporal bone, or inner ear, which forms in early childhood and resists alteration even during cremation.

Reading Mobility in Bone Chemistry

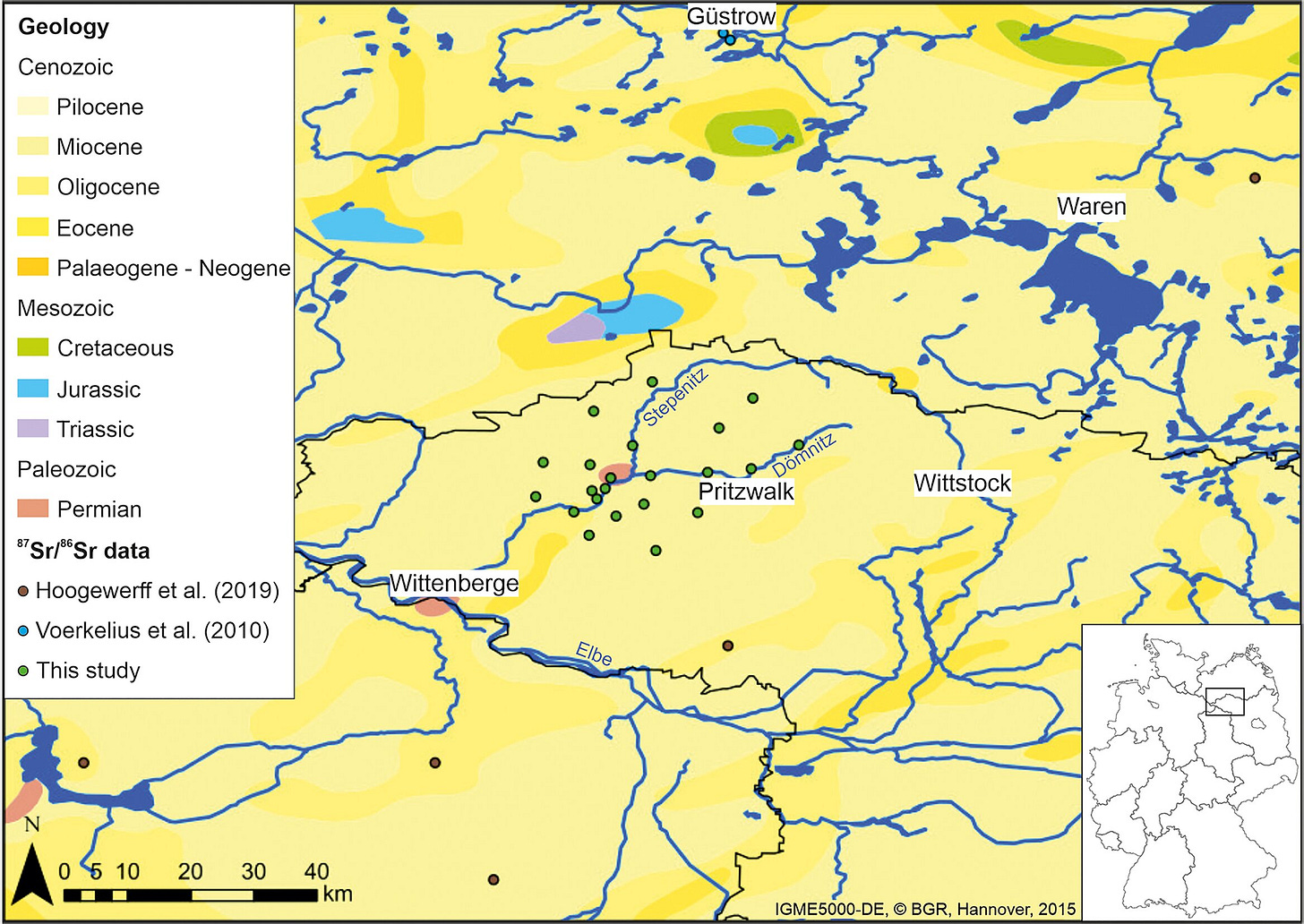

Strontium isotopes, derived from the local geology, enter the food chain through plants, animals, and drinking water. When children grow, their bones and teeth lock in a regional chemical “signature.” Comparing this signature in human remains to the local baseline allows archaeologists to tell whether an individual grew up in the same area where they were buried.

The Seddin study compared the isotope ratios of 30 cremated individuals to a reference baseline built from local soils and waters. The results show that most of the sampled individuals had isotope values incompatible with the Seddin region but consistent with regions such as southern Scandinavia, central Europe, and possibly northern Italy.

“Identifying the area of origin is less straightforward, as multiple areas can have the same strontium composition,” Dr. Frank noted. “We narrowed it down further using the archaeological record.”

Elite Networks and the Movement of Ideas

The isotope results dovetail with decades of artifact studies. For example, horned helmets appear in both Sardinia and Scandinavia at the same time, while Scandinavian-style razors and Italian bronze vessels occur in northern Europe. The new data suggest that such items were not only traded but also accompanied by people who may have brokered or controlled exchange networks.

Dr. Serena Sabatini, co-author of the study, highlights that Seddin’s elite dead fit within a broader European pattern of mobility during the Late Bronze Age. “This was a time when the value of bronze shifted, trade routes realigned, and elite groups across Europe began forging new identities,” she said.

Reconsidering “Local” Bronze Age Communities

The Seddin study prompts a reassessment of what archaeologists call “local culture.” Monumental mounds, elite goods, and isotope data together suggest that the elites of Seddin were at least partly foreign-born, their status tied to their ability to mobilize distant connections.

This pattern mirrors findings from other parts of Europe, such as the Lech Valley in southern Germany, where isotope studies have shown that high-status women were often migrants. Taken together, these studies depict a Bronze Age world far more fluid, mobile, and interconnected than once assumed.

Related Research

Knipper, C., Mittnik, A., Massy, K., et al. (2017). Female exogamy and gene pool diversification at the transition from the Final Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age in central Europe. PNAS, 114(38), 10083–10088. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706355114

Frei, K. M., Mannering, U., Kristiansen, K., et al. (2015). Tracing the life story of a Bronze Age woman from Egtved, Denmark. Scientific Reports, 5, 10431. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10431

Price, T. D., Frei, K. M., & Frei, R. (2015). Strontium isotopes and human mobility: A geochemical approach to archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 44, 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-013854

Frank, A. B., May, J., Sabatini, S., Schopper, F., Frei, R., Kaul, F., Storch, S., Hansen, S., Kristiansen, K., & Frei, K. M. (2025). A Late Bronze Age foreign elite? Investigating mobility patterns at Seddin, Germany. PloS One, 20(9), e0330390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0330390