Old Words in New Places

Languages leave trails, even when the speakers vanish. Names persist in rivers and mountains. Sounds travel through borrowed words. Now, an interdisciplinary analysis of ancient loanwords, glosses, personal names, and toponyms has traced the linguistic fingerprint of one of history’s most enigmatic groups—the Huns—back to a Siberian language most had never heard of: Old Arin, a member of the Yeniseian family.

A recent study1 by linguists Svenja Bonmann (University of Cologne) and Simon Fries (University of Oxford) provides the strongest case yet that both the Xiōng-nú—a nomadic empire that ruled the Central Asian steppe from the 3rd century BCE to the 2nd century CE—and the European Huns of the 4th–5th centuries CE spoke a common language: a Paleo-Siberian tongue now extinct, but once widespread across Inner Asia.

"The Huns and Xiōng-nú likely spoke Old Arin, a Yeniseian language," write the authors, "implying a direct cultural and linguistic link between Eurasia's ancient east and its distant west."

Who Were the Xiōng-nú and the Huns?

The Xiōng-nú were not just any nomads. For centuries, they ruled over the grasslands of Mongolia, Dzungaria, and beyond. Some Chinese sources describe them as ferocious warriors; others refer to elaborate diplomatic ties with Han emperors. The Huns, who burst into the Roman imagination centuries later under Attila’s banner, were similarly elusive—a mobile empire without written records in their own tongue.

While historians have long debated whether the Huns were direct descendants of the Xiōng-nú, this study introduces a novel line of evidence: the language they may have shared.

Following the Linguistic Trail

Bonmann and Fries analyze four main categories of evidence:

Loanwords in Turkic and Mongolic Languages

They identify five core words—terms for "water," "rain," "silver," "birch," and "lizard"—present in both Turkic and Mongolic languages but best explained as loans from a Yeniseian source. All five share a phonological pattern typical of Arin, and not seen in other Yeniseian languages like Ket or Yugh.

“These words reflect core vocabulary—natural elements tied to daily life and geography—which are unlikely to have been borrowed lightly or late,” explains Fries.

The presence of these Arin-derived words in Proto-Turkic and Proto-Mongolic suggests early and intense contact—before those language families even fully formed.Glosses in Chinese Texts

The few known phrases attributed to the Xiōng-nú in early Chinese chronicles bear striking resemblance to Arin grammatical structures. A pair of military phrases preserved in the Jin shu (7th century CE) exhibit verb endings in -taŋ—a third-person plural marker otherwise attested only in Arin.Personal Names and Titles

Names attributed to Hunnic elites, including Attila, show patterns that align more with Yeniseian roots than previously assumed Turkic or Germanic ones. For instance, “Attila” may derive not from a Gothic nickname meaning “little father,” but from an Arin word meaning “swift” or “quick-like.”

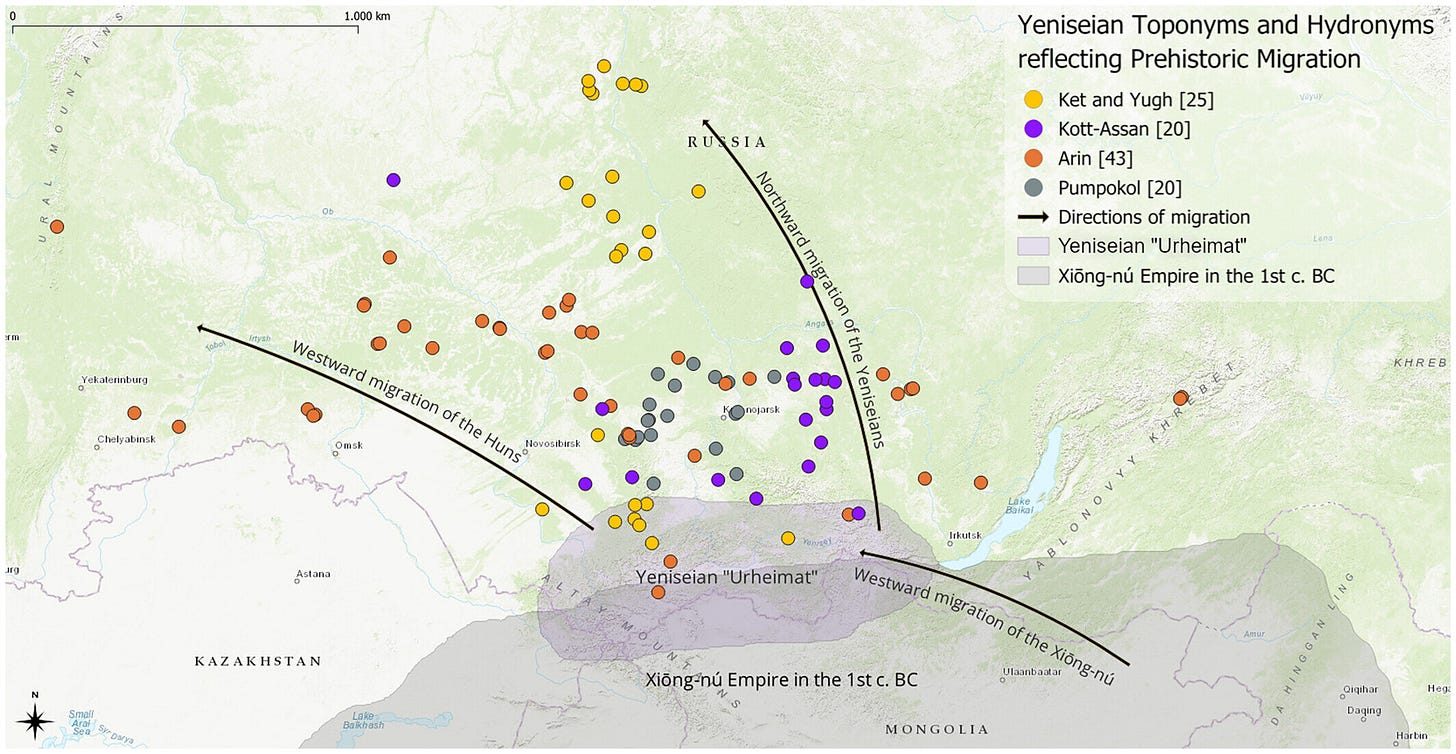

Toponyms and Hydronyms

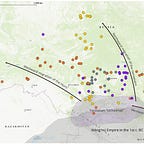

Place names across Inner Asia and into Eastern Europe suggest a westward trail of Arin-speaking populations—matching the trajectory of the Huns from the Altai-Sayan region to the Carpathian Basin.

Implications for Eurasian History

If Bonmann and Fries are correct, then the story of the Huns and the Xiōng-nú is not simply one of cultural similarity, but of linguistic continuity over hundreds of years and thousands of kilometers. This supports a hypothesis first posed in the 18th century—that the Huns descended from Xiōng-nú refugees who fled westward after the collapse of their empire.

"Old Arin was not a language of the margins," the authors argue. "It likely served as the prestige language of a ruling elite whose cultural influence spread widely across Eurasia."

Recent genetic studies back this up. One analysis (Gnecchi-Ruscone et al., 2025) found long segments of shared DNA between Xiōng-nú elites and individuals buried in the Carpathian Basin—implying a biological as well as linguistic link.

What About Turkic and Mongolic Roots?

The traditional view that the Huns were Turkic-speaking has been based largely on an absence of evidence rather than compelling proof. Written Turkic appears centuries after the Huns. Mongolic inscriptions appear even later. And while Iranian languages did coexist in the same regions, they were likely spoken by minority groups within these multiethnic confederations.

Bonmann and Fries emphasize that their argument does not deny diversity within these polities. Rather, it points to a specific linguistic heritage tied to the elite ruling dynasties.

The Return of a Forgotten Voice

The Arin language, now extinct and long overshadowed by its more famous neighbors, may have once shaped the empires that terrified the Roman world and reshaped Inner Asia.

“Comparative philology doesn’t just recover words—it recovers worlds,” writes Bonmann.

In this case, that world stretched from the steppes of Mongolia to the Danube frontier of Rome, carried not just by horses and armies, but by a language now whispering through old glosses, place names, and the syllables of a forgotten empire.

Related Research

Gnecchi-Ruscone, G. A., et al. (2025). Genomic connections between Xiongnu elites and European Huns. Nature Genetics. [DOI: 10.1038/s41588-025-01500-7]

Vovin, A. (2000). Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language? Central Asiatic Journal, 44(1), 87–104. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/41928383]

Fries, S., & Bonmann, S. (2023). Reconstructing Proto-Yeniseian Phonology: An Internal and External Approach. Journal of Historical Linguistics, 13(2), 301–344.

Vajda, E. J. (2019). The Yeniseian Languages: Origins, Relationships, and Cultural Contexts. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Contact. Oxford University Press. [https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199945691.013.25]

Bonmann, S., & Fries, S. (2025). Linguistic evidence suggests that Xiōng‐nú and Huns spoke the same Paleo‐Siberian language. Transactions of the Philological Society. Philological Society (Great Britain). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-968x.12321