A Forgotten Landscape

For decades, archaeologists pictured the heart of the Iberian Peninsula—the vast central plateau known as the Meseta—as a barren expanse bypassed by the first Homo sapiens. After Neanderthals disappeared, it was assumed that this cold and arid interior remained nearly empty until modern humans returned near the end of the Last Glacial Maximum.

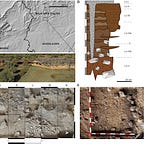

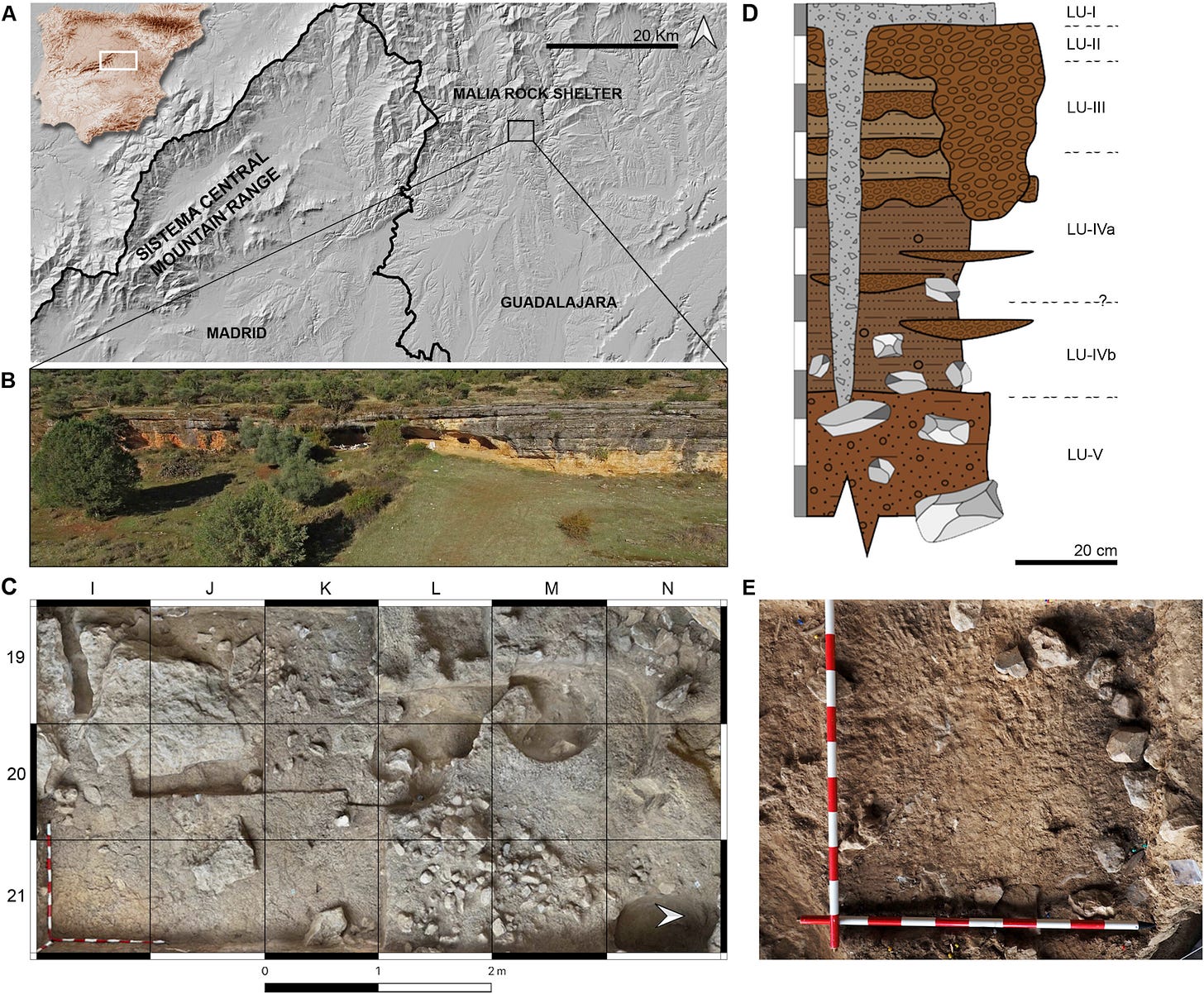

A new study1 from the rock shelter of Abrigo de la Malia in Guadalajara upends that assumption. Dating to between 36,200 and 26,260 years ago, the site preserves faunal remains that capture the lives of hunters who not only ventured into the Meseta but returned often enough to leave a record stretching over 10,000 years.

“The zooarchaeological and taphonomic evidence documents short but recurrent occupations over at least 10,000 years,” the authors write. “This pattern demonstrates that climatic deterioration during the Early Upper Paleolithic did not significantly alter the settlement patterns or subsistence strategies of Homo sapiens.”

What the Bones Reveal

The Malia assemblage is dominated by medium and large ungulates—red deer, wild horses, bison, and chamois. Cut marks and bone fractures show that humans, not carnivores, were the primary agents of processing. The hunters skinned, butchered, and cracked bones for marrow.

“Taphonomic data suggests primary and almost exclusive anthropic processing of medium and large-sized ungulates, from skinning to marrow extraction”

These patterns suggest the site was not a permanent home but a recurrent hunting camp. Groups likely stopped at Malia to process carcasses after nearby kills, leaving behind bones, lithics, and traces of hearths before moving on.

Climate Windows and Human Resilience

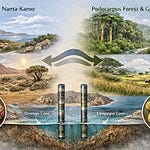

Malia’s sediments preserve ecological shifts. Around 35,000 years ago, climatic amelioration in the Submediterranean zone boosted herbivore biomass, creating what researchers describe as “ecological windows of opportunity” that drew human groups inland.

As conditions worsened, with forests giving way to colder open landscapes, humans adapted by continuing to target reliable game. The resilience of these groups contradicts older models that portrayed the plateau as uninhabitable during the harsh climate of Marine Isotope Stage 3.

Challenging Old Narratives

Previous research focused on coastal refuges, where rich archaeological layers painted a picture of Upper Paleolithic life concentrated along the Cantabrian, Atlantic, and Mediterranean margins. By contrast, sites in the Meseta seemed scarce, reinforcing the idea of a depopulated heartland.

Malia forces a reassessment. Its evidence shows that early Homo sapiens were capable of exploiting upland, forested, and grassland environments—even under deteriorating climates.

“Malia allows us to characterize human behavior in the early Upper Paleolithic and provides insight into the resilience of the first Homo sapiens to successfully colonize challenging and resource-scarce territories”

A Plateau Not Empty, but Alive

Malia joins a growing list of sites suggesting the Meseta was never a true void. Short-term occupations like those at Los Enebrales and Peña Capón hint at repeated visits by hunting groups. Seen together, they suggest a mosaic of mobility strategies: sometimes seasonal camps, sometimes task-specific stopovers, always tied to the rhythms of climate and prey.

Why It Matters

The discovery repositions central Iberia within broader debates about how early modern humans spread across Europe. It suggests that their colonization strategies were not limited to resource-rich coasts but extended into demanding interior environments.

This resilience adds nuance to the story of human dispersal: Homo sapiens were not simply opportunistic invaders of easy landscapes but skilled hunters able to extract sustenance from difficult ecologies.

Related Research

Alcaraz-Castaño, M., et al. (2017). “The human settlement of Central Iberia during MIS 2: new technological, chronological and environmental data from the Solutrean workshop of Las Delicias.” Quaternary International, 431, 104–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.001

Vidal-Cordasco, M., et al. (2022). “Ecological opportunities and the persistence of Upper Paleolithic populations in Iberia.” Quaternary Science Reviews, 286, 107523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107523

Lombera-Hermida, A., et al. (2021). “Subsistence and settlement strategies at Cova Eirós during the Upper Paleolithic.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 38, 103061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103061

Sanchis, A., et al. (2023). “Short-term occupations in the Upper Paleolithic: faunal insights from Cova de les Malladetes.” Quaternary International, 685–686, 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2023.03.005

Téllez, E., Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A., Rodríguez-Almagro, M., Núñez-Lahuerta, C., Arteaga-Brieba, A., Pablos, A., & Sala, N. (2025). Subsistence strategies in the early upper Paleolithic of central Iberia: Evidence from Abrigo de la Malia. Quaternary Science Advances, 19(100297), 100297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qsa.2025.100297