A Place for the Ancestors

In a clearing not far from the ceremonial heart of Ceibal—one of the oldest known monumental centers in the Maya lowlands—archaeologists have uncovered something unexpected: a cemetery. Not a scattering of isolated burials, but a coherent mortuary landscape that predates the city’s famous pyramids and plazas.

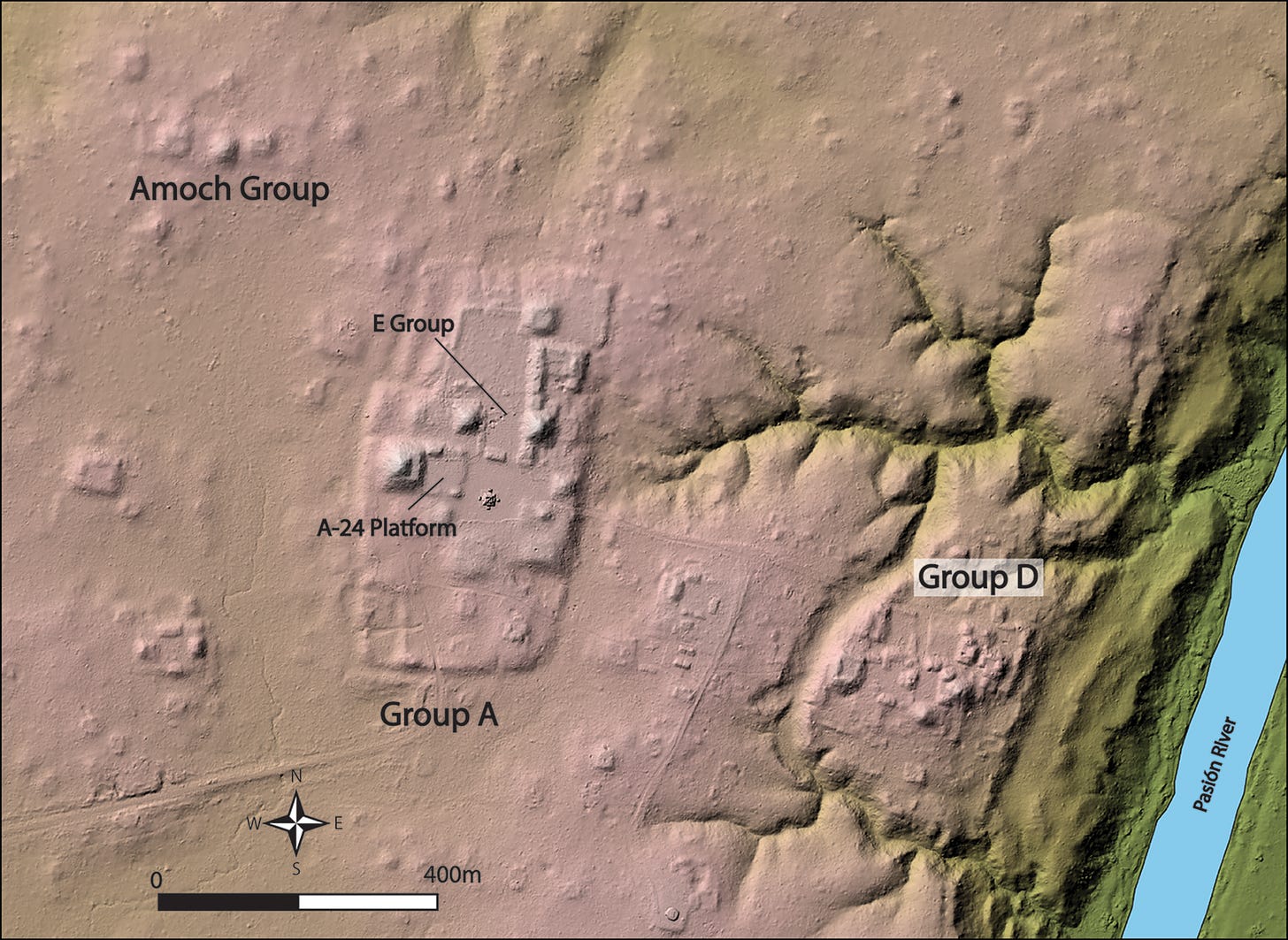

This burial ground, located in a minor ceremonial complex known as the Amoch Group, dates to between 1100 and 800 BCE—well before stone buildings filled the landscape or pottery became ubiquitous in daily life. According to a recent study published in Antiquity1, the Amoch cemetery may represent a brief but important chapter in the Preceramic to Preclassic transition, when people began to anchor themselves to land, tradition, and one another in new ways.

“The establishment of the Amoch Cemetery was most likely tied to profound social change, involving decreased mobility, increased reliance on maize, and the development of ceremonial complexes.”

The Bones Between Worlds

Archaeologists working at Ceibal have long grappled with the paradox of an early ceremonial center that lacked clear evidence of permanent domestic settlement. The central E-Group complex—built by 950 BCE—was used for solar observation and ritual gathering, but where the early people of Ceibal lived and how they organized themselves remained murky.

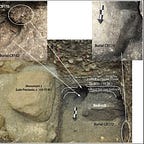

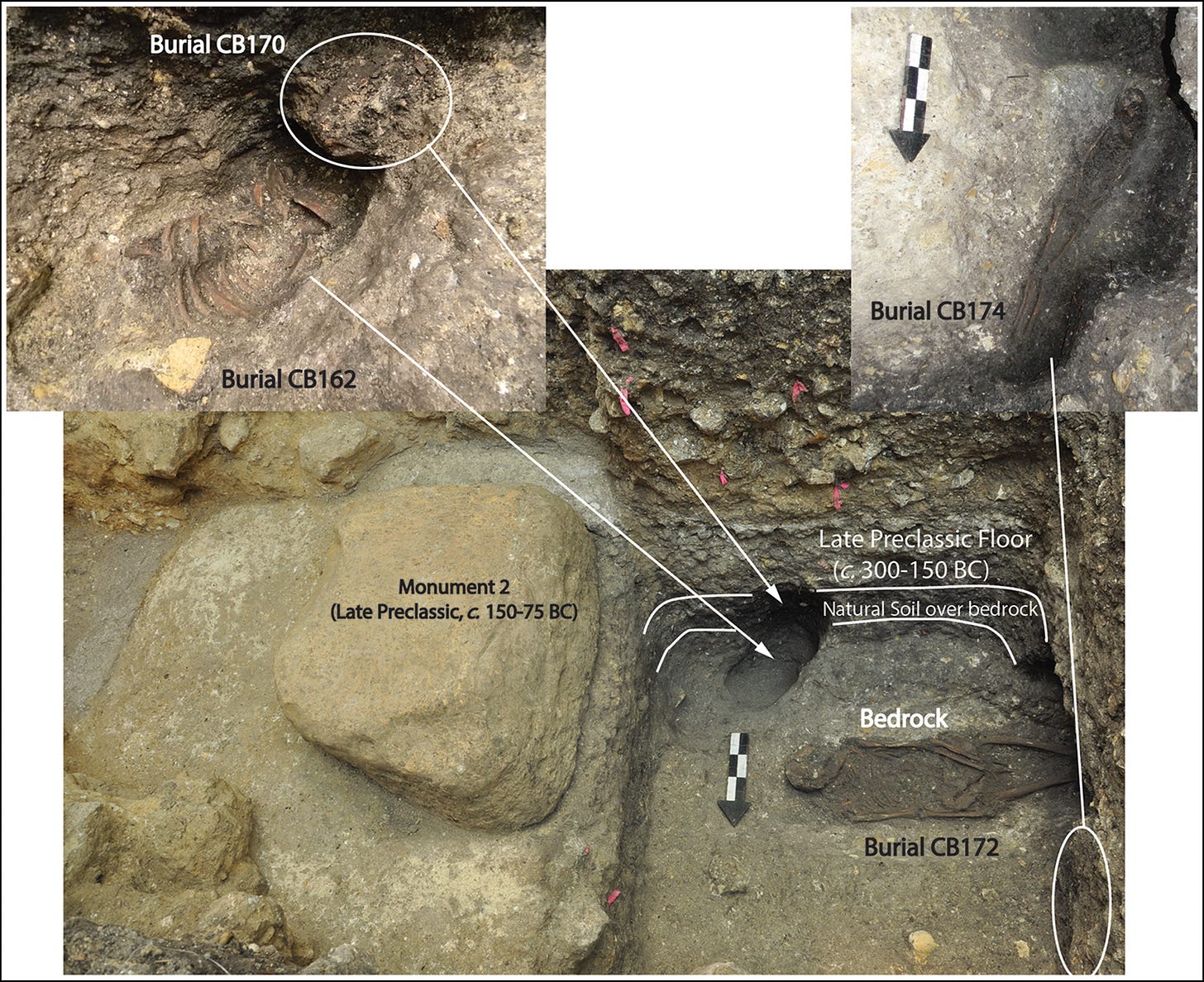

Between 2014 and 2023, researchers excavated 26 burials at the Amoch Group, a modest platform complex about half a kilometer from the site’s main plaza. The interments were layered within a thin band of natural soil just above the bedrock—an archaeological twilight zone too early for fully sedentary life, yet too late to be purely foraging.

“These burials reflect a different mortuary practice, one that seems to emphasize social groups rather than individuals.”

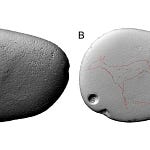

Few grave goods accompanied the dead. Only one burial included durable offerings—spherical stones that may have served as weapons or symbolic markers. Most were laid in extended supine positions, arms folded across pelvises or chests. Some were flexed at the knees. In several cases, later Preclassic construction disturbed or carefully repositioned earlier remains, suggesting that their location held enduring meaning.

Death Without Prestige

What’s most striking about the Amoch cemetery is its egalitarian tone. Individuals of all ages were interred—infants, young adults, and the elderly alike. There is no clear pattern of elite burial, no wealth markers or indicators of political status. In contrast to later Maya practices, where burials under houses signified lineage power and territorial claims, the Amoch dead were laid to rest in a communal space outside domestic architecture.

“It was not reserved for select individuals with special status, or at least any distinctions cannot be detected archaeologically.”

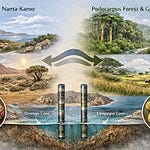

Dental analysis revealed high rates of porotic hyperostosis—likely linked to anemia—and considerable tooth decay, consistent with diets in early agricultural societies. Stable isotope analysis from a handful of burials suggests a moderate maize intake, supplemented by meat and aquatic resources. These people were no longer pure foragers, but neither had they fully adopted the sedentary life of maize farmers.

Cemeteries Before Cities

The presence of a dedicated cemetery from this transitional moment challenges old assumptions. Across the globe, formal burial grounds often emerge alongside sedentism and increasing territoriality. But at Ceibal, the Amoch cemetery may have come first, anchoring ritual and memory in the land before temples rose.

“The decision to build the E Group at this location may have been influenced by its proximity to the cemetery—a culturally meaningful place.”

This raises questions about how early Maya communities used burial to shape identity, space, and belonging. If ancestor veneration was already forming the social glue of emerging communities, it may have laid the ideological groundwork for later forms of kingship, lineage-based rule, and sacred geography.

Pottery and Its Absence

Curiously, no pottery was found with these early burials. This absence raises two possibilities. One is that the cemetery predated ceramic adoption entirely. Another is that pottery had already entered the cultural toolkit, but was not used in mortuary practice—at least not at Amoch. In either case, the simplicity of the graves suggests that ritual and remembrance did not yet rely on durable symbols of wealth or hierarchy.

“The group who used the Amoch Cemetery may not have adopted pottery, even after those closely associated with the E Group began to use ceramics.”

The Quiet Beginnings of Maya Civilization

Ceibal has often served as a case study for how monumentality can precede urbanization. The Amoch cemetery adds another layer: even before temples, people were building social landscapes—through burial, remembrance, and shared space. The persistence of this burial ground, even as construction overtook the site in later centuries, speaks to its significance.

This early cemetery offers a rare window into the messy, overlapping phases of cultural transformation. The dead of Amoch were neither fully mobile nor fully settled. Their lives straddled a threshold. And yet, they were remembered. Their bones, positioned with care, speak to the beginnings of a place that mattered.

Related Research

Inomata, T., et al. (2015). Development of sedentary communities in the Maya Lowlands: coexisting mobile groups and public ceremonies at Ceibal, Guatemala. PNAS, 112(14), 4268–4273. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1501212112

Prufer, K. M., et al. (2021). Terminal Pleistocene through middle Holocene occupations in southeastern Mesoamerica: linking ecology and culture in the context of the neotropical foragers and early farmers. Ancient Mesoamerica, 32(3), 439–460. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536121000195

Awe, J., et al. (2021). Lowland Maya genesis: the Late Archaic to late Early Formative transition in the Upper Belize River Valley. Ancient Mesoamerica, 32(3), 519–544. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536121000420

Stemp, W. J., et al. (2021). The Preceramic and early Ceramic periods in Belize and the Central Maya Lowlands. Ancient Mesoamerica, 32(3), 416–438. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536121000444

Burham, M., Palomo, J. M., Pinzón, F., Véliz Corado, F. J., & Inomata, T. (2025). A Preceramic–Preclassic transition cemetery at the Lowland Maya site of Ceibal, Guatemala. Antiquity, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.76