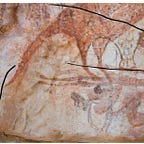

At first glance, the animal figures painted on rock shelters in the northeast Kimberley look deceptively simple—thin outlines of kangaroos, some barely adorned, others stylized into abstract form. For decades, they were thought to be remnants of an earlier, Ice Age aesthetic, part of a vast visual tradition called the Irregular Infill Animal Period (IIAP). But recent work suggests these understated images belong not to the deep Pleistocene past but to a period of social and environmental flux several millennia later.

In a new study published in Australian Archaeology1, Ana Paula Motta and colleagues, in partnership with the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation, have proposed that these figures represent a distinct rock art style they call the Linear Naturalistic Figures (LNF). Unlike earlier interpretations that folded them into IIAP, the LNF style reflects a return to large animal imagery during the Mid-to-Late Holocene—between roughly 6,000 and 1,000 years ago—after a long period in which anthropomorphic and multicolored imagery dominated.

"We proposed that the LNF belongs to the Mid-to-Late Holocene, a period characterized by changing socio-environmental conditions," Motta explains.

This recognition emerged from the Kimberley Visions project, a sweeping survey of over 1,100 archaeological sites across the Drysdale and King George River catchments. Of the 151 rock art sites identified, 22 preserved animal depictions that broke stylistically with the earlier IIAP tradition. These 98 motifs—nearly all macropods—were less dynamic, more linear, and painted in outline without complex infill, suggesting a different visual language altogether.

Reassessing Style, Rethinking Time

The IIAP tradition, which emerged during the terminal Pleistocene (ca. 17,200–13,000 years ago), is renowned for its dynamic renderings of animals in motion—painted with irregular brushstrokes and complex infill designs. By contrast, the LNF motifs lack these flourishes. Instead, they are composed of clean lines and rendered in static profile, rarely layered with pigment.

"The IIAP style, despite being defined as containing naturalistic animals with irregular brushstrokes, in reality contains a high diversity of forms," says Motta. "It was first important to disentangle the main attributes of IIAP and then proceed to describe LNF motifs."

What makes the LNF style particularly interesting is its chronological positioning. These figures are often superimposed over older rock art styles like IIAP, Gwion (ca. 14,000–12,000 BP), and Static Polychrome (12,000–9,000 BP), while themselves sometimes underlying Wanjina paintings, which are associated with more recent historical periods. This stratigraphic ordering helps situate the LNF tradition securely within the Mid-to-Late Holocene.

Animals, Identity, and the Mid-Holocene Turn

The simplicity of the LNF style belies a deeper cultural significance. During the Mid-Holocene, sea levels had stabilized, new stone technologies appeared, and groups in the Kimberley region likely became more territorially constrained. Linguistic diversification was also underway. Against this backdrop of demographic and environmental shifts, a return to large animal imagery might have served as a stabilizing force—offering symbolic continuity amid growing social complexity.

"We argue that groups returned to depicting large naturalistic animals, particularly macropods, during a time of increased change, where rock art acted as a mechanism to mediate this change," the study notes.

The recurrence of macropods in LNF paintings isn’t simply aesthetic. These animals—kangaroos and wallabies—hold deep spiritual and economic significance. In Aboriginal cosmologies, animals are kin, law-givers, and totems. The act of painting them may have reinforced social identities, marked territory, or expressed continuity with ancestral laws.

A Living Archive

The recognition of the LNF style expands not just the art historical timeline but also challenges archaeological assumptions about simplicity in form implying antiquity. The rock surfaces of the Kimberley are now understood as layered palimpsests, carrying traces of shifting cultural practices and ecological adaptations.

If the Gwion and Static Polychrome periods reflect increased abstraction and anthropomorphism, the emergence of LNF motifs signals a return to zoomorphic clarity. This pivot was not regression but rearticulation—visual culture re-centering on animals at a time when society itself may have been renegotiating its relationship with land, law, and lineage.

What emerges is not just a new "style" but a renewed understanding of art as a strategy for living through change.

Related Research

David, B., McNiven, I. J., Delannoy, J. J., & Watchman, A. (2013). The Archaeology of Rock Art in Western Arnhem Land, Australia. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155528

Ross, J., Westaway, M., Travers, M., Morwood, M. J., & Hayward, J. (2016). Buried in the Sand: Archaeological and Anthropological Investigations of Indigenous Burial Traditions on Cape York Peninsula, Australia. Antiquity, 90(354), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2016.2

Taçon, P. S. C., Wilson, M., & Chippindale, C. (1996). Birth of the Rainbow Serpent in Arnhem Land Rock Art and Oral History. Archaeology in Oceania, 31(3), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1834-4453.1996.tb00347.x

Motta, A. P., Ouzman, S., Veth, P., & Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation. (2025). Linear Naturalistic Figures: a new Mid-to-Late Holocene Aboriginal rock art style from the northeast Kimberley, Australia. Australian Archaeology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2025.2457860