A State in the Stones

For more than a century, the ancient city of Tiwanaku has fascinated archaeologists and confounded their maps. Perched near Lake Titicaca, the site was once the heart of a sprawling civilization that shaped the Andes long before the Inca. But how far did its influence really stretch?

A new discovery1, quietly documented during a Bolivian road expansion survey, offers a striking piece of that puzzle: a monumental temple known locally as Palaspata, built 130 miles southeast of Tiwanaku’s ceremonial core, and possibly aligned with the equinox sun.

In its sunken courtyards and carved stone walls, archaeologists see not just a temple, but a political instrument, part ritual site, part transit hub, strategically placed where highland herders, valley farmers, and long-distance caravans converged.

“Palaspata likely functioned as a ritual gateway between two major contrasting ecological and productive regions,” notes archaeologist José Capriles of Penn State, who led the study published in Antiquity (2025). “Ceremonies held here might have sacralised the flow of people and goods.”

Where Gods and Goods Met

Built sometime between the 7th and 10th centuries CE, the Palaspata complex isn’t just big—it’s calculated. Measuring roughly 125 by 145 meters, its 15 rectangular enclosures frame an inner plaza, a design echoing temples at Tiwanaku itself and its far-flung colonial outposts like Omo M10 in southern Peru.

Archaeologists found ceramic fragments of keru drinking vessels, used to consume chicha, a maize beer central to ritual feasting, alongside turquoise stones and even marine shells from the Pacific coast. These were not local offerings. They had traveled.

“Maize didn’t grow here,” Capriles explains. “It had to be brought from the eastern Cochabamba valleys. That tells us something about the site’s role in integrating distant landscapes.”

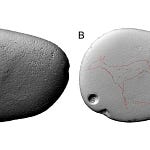

The complex wasn’t buried deep beneath the soil or jungle. In fact, local farmers had long known of the hilltop ruins, but their full extent remained obscured until archaeologists stitched together drone imagery and satellite photos. The result was a virtual excavation of a city block–sized ceremonial hub, invisible to ground-level eyes.

Rethinking Tiwanaku’s Reach

Tiwanaku is often portrayed as a ceremonial kingdom, a kind of Andean Mecca where pilgrims came to worship and leave offerings. Yet this framing underplays the logistical and political sophistication it wielded. Palaspata provides tangible evidence that Tiwanaku’s influence extended east, not just as religious soft power, but as material control.

Radiocarbon dates from nearby domestic areas at Ocotavi 1 show sustained occupation between 630 and 950 CE, matching Tiwanaku’s peak. Residents built homes, buried their dead with elaborately decorated pottery, and hosted a mix of highland and valley ceramic styles, reflecting regional integration.

“This is not just a place of prayer,” said co-author Sergio Calla Maldonado. “It’s where the sacred and administrative merged to manage goods, people, and cooperation.”

Crucially, Palaspata sits at the intersection of three ecological zones:

The Titicaca highlands, home to llama herders and Tiwanaku’s heartland.

The arid Altiplano, a corridor for caravan routes.

The fertile valleys of Cochabamba, where maize and tropical crops thrived.

This tripoint position was no accident. Empire builders understood geography.

Stones, Slopes, and Sovereignty

What makes Palaspata particularly compelling is its architectural language. It speaks not only to Tiwanaku aesthetics, sunken courts, red sandstone perimeter walls, alignments with celestial events, but also to its imperial grammar: the use of sacred architecture to materialize political control.

Such monumental complexes were not unique to Tiwanaku. The Wari state, its contemporary to the north, used D-shaped temples to project authority across Peru. But in Palaspata, Tiwanaku seems to have adapted a more modular approach, blending ritual practice with economic logistics. Think of it as a ritual toll booth: part sanctuary, part checkpoint.

As Capriles and colleagues point out, this wasn’t an isolated shrine. It was part of a broader 75-hectare settlement, integrated into a network of temples, plazas, and terraces. The site’s ceramic assemblage includes styles from the eastern valleys and even the Atacama, signaling an active flow of goods, and perhaps ideas, across ecozones.

A Gateway Reopened

In many ways, Palaspata was hiding in plain sight. While some of its stones were pilfered for nearby construction or displaced by agriculture, its footprint endured, just enough for archaeologists to see its symmetry from above.

Today, local leaders are working with national authorities to preserve the site and integrate it into Bolivia’s cultural heritage. For the municipality of Caracollo, it is both a source of pride and a potential draw for sustainable tourism.

“The archaeological findings at Palaspata highlight a crucial aspect of our local heritage that had been completely overlooked,” said Justo Ventura Guarayo, Caracollo’s mayor.

Toward an Eastern Horizon

Tiwanaku’s legacy has long been understood through the monumental ruins clustered around Lake Titicaca. But Palaspata pushes that story outward, toward the eastern escarpments of the Andes.

It suggests a civilization more expansive and infrastructurally savvy than some narratives have allowed. One that didn’t merely preach across landscapes, but built into them, using temples as anchors of cooperation, trade, and cosmic order.

*“With more insight into the past of this ancient site,” Capriles reflects, “we get a window into how people managed cooperation—and how we can materially see evidence of political and economic control.”

The Andes, it seems, still have secrets to share, etched not in gold, but in the carved stones of a wind-blown hill.

Additional Related Research

Goldstein, P.S. (2006). Andean diaspora: the Tiwanaku colonies and the origins of South American empire. University Press of Florida.

Delaere, C., Capriles, J.M., & Stanish, C. (2019). Underwater ritual offerings in the Island of the Sun and the formation of the Tiwanaku state. PNAS, 116(17), 8233–8238. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820749116

Goldstein, P.S., & Sitek, M.J. (2018). Plazas and processional paths in Tiwanaku temples: Omo M10, Moquegua, Peru. Latin American Antiquity, 29(3), 455–474. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2018.26

Reid, D.A. (2023). The role of temple institutions in Wari imperial expansion at Pakaytambo, Peru. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 69, 101485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2023.101485

Marsh, E.J., et al. (2023). The center cannot hold: a Bayesian chronology for the collapse of Tiwanaku. PLoS ONE, 18(7), e0288798. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288798

Capriles, J. M., Calla Maldonado, S., Calero, J. P., & Delaere, C. (2025). Gateway to the east: the Palaspata temple and the south-eastern expansion of the Tiwanaku state. Antiquity, 99(405), 831–849. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.59