When archaeologists discuss the skills that allowed Homo sapiens to eclipse other hominins, they often cite symbolic behavior, complex tools, or language. But beneath these visible traits lies something less tangible: the capacity to focus. Paying attention — selectively, deeply, and flexibly — shapes how humans plan, hunt, and cooperate. A recent paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science1 explores how this trait may have emerged from subtle differences in neurogenetics among modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans.

Genes as Clues to Ancient Minds

Marlize Lombard, a cognitive archaeologist at the University of Johannesburg, set out to examine which genes linked to attention in Homo sapiens show differences in the Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes. Ancient DNA now provides full genome sequences of both extinct relatives, allowing researchers to ask new questions about their cognition.

“Paying attention in complex ways is one of the things that humans do differently from all animals today,” Lombard notes. “The question is how far back this ability goes — and whether our cousins shared it.”

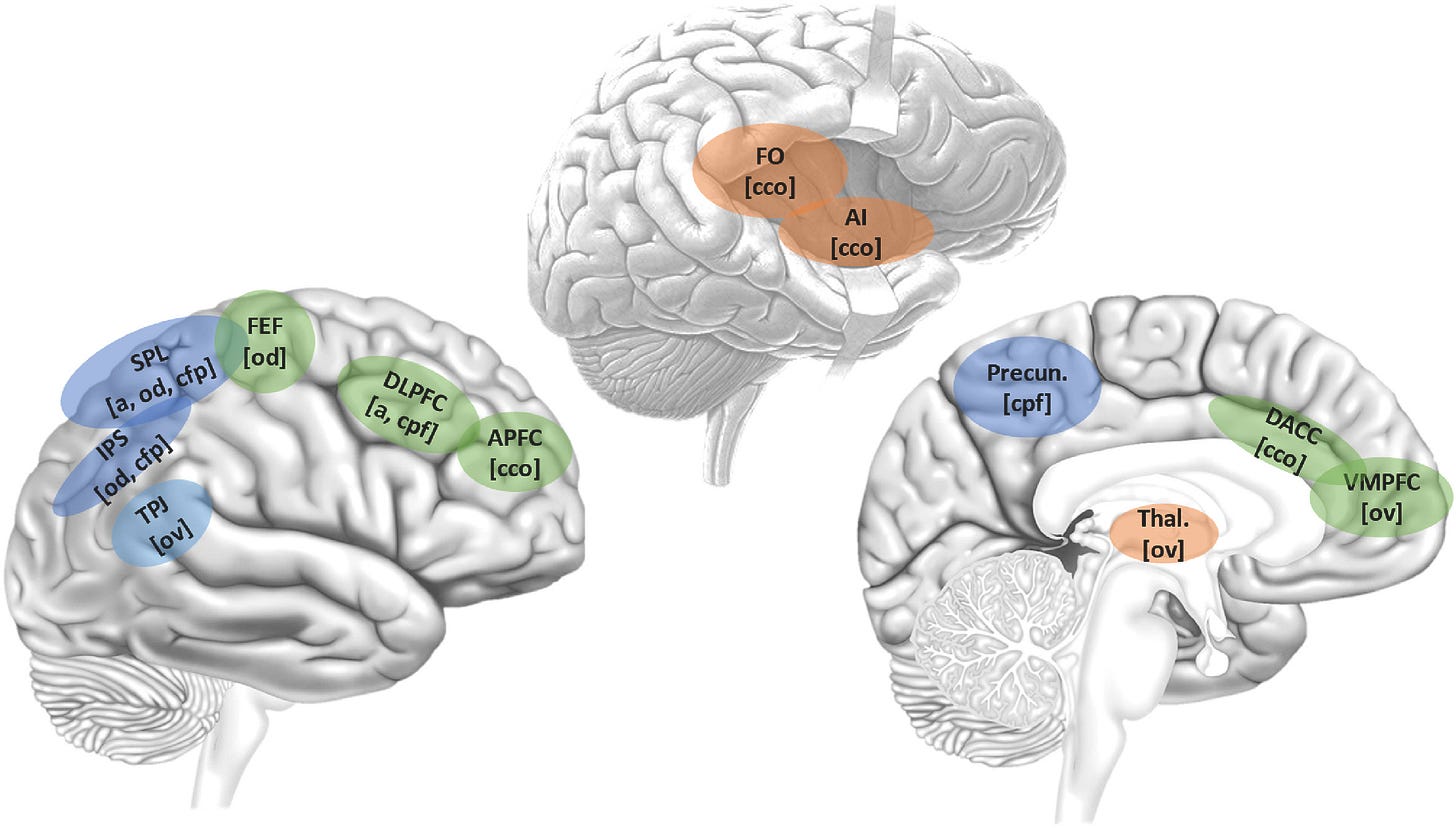

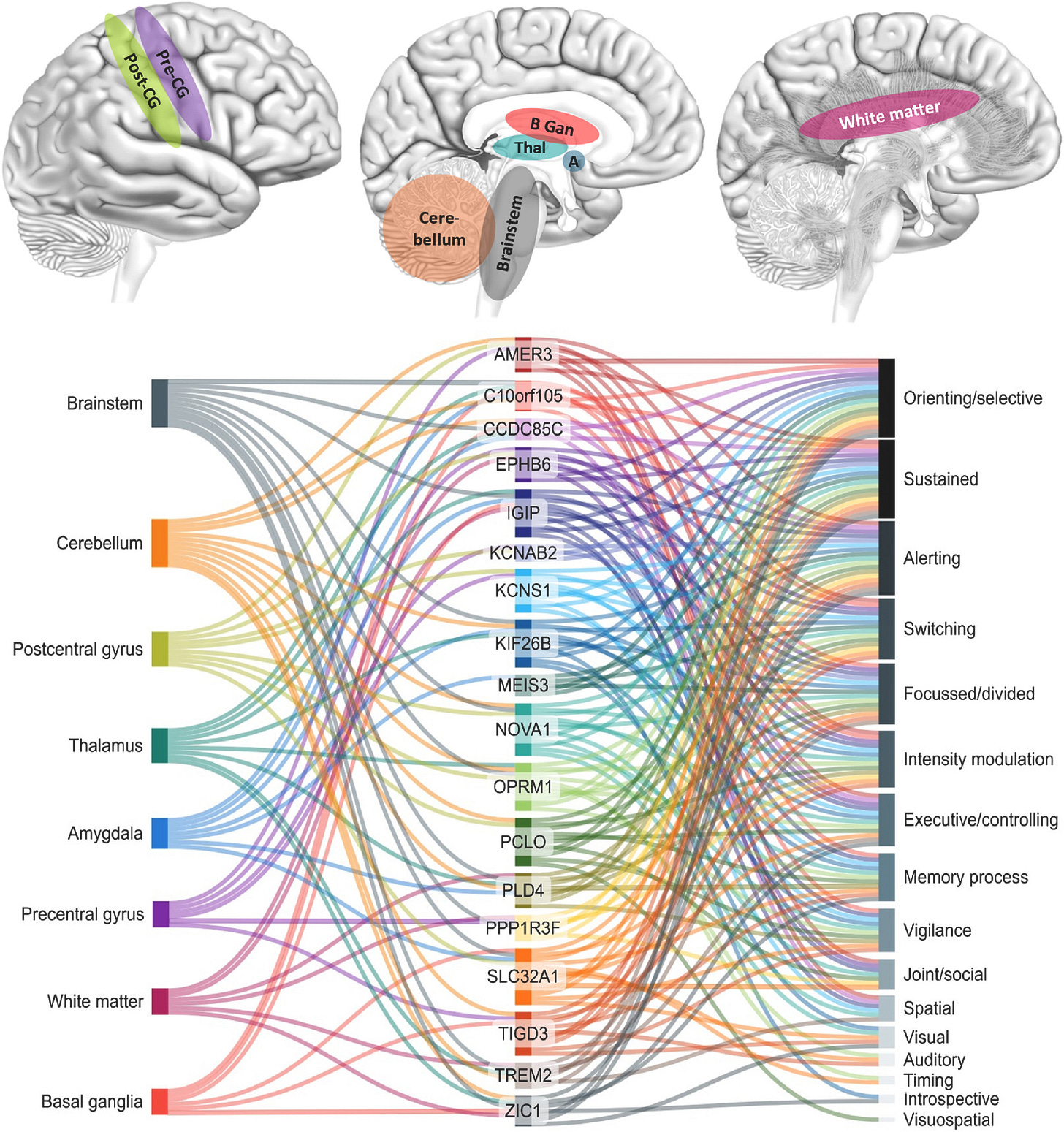

By sifting through published datasets, Lombard identified 180 genes associated with attention in Homo sapiens that differ from those in Neanderthals and Denisovans. Eighteen were highly expressed in specific brain regions, including the brainstem, cerebellum, amygdala, basal ganglia, white matter, and thalamus. Many of these regions are typically considered “ancient” brain structures, not the obvious centers of higher cognition.

“These subcortical regions, along with the thalamus, are implicated in the evolution of human attention and deserve more focused study,” Lombard argues.

The Surprising Role of the “Reptile Brain”

In modern neuroscience, the brainstem and cerebellum are often cast as housekeeping centers of movement, balance, and automatic processing. Yet recent research shows they also regulate sensory integration and attention. Clinical neuroscientist Samantha Abram, who studies psychosis at the University of California San Francisco, finds the overlap striking.

“I was struck by the fact that this paper found the cerebellum and brainstem were huge contributors to the evolution of attention,” Abram says. “It’s another line of evidence that these areas play a role in human thinking, not just basic processing.”

The implication is that Homo sapiens may have developed faster, more efficient “relay hubs” for attention compared to Neanderthals and Denisovans — a neurological advantage that could ripple out into planning, tool use, and social learning.

Limits and Caution

Other scholars urge caution. Cedric Boeckx, an evolutionary neuroscientist at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies, emphasizes that genetic differences do not automatically translate to behavioral differences.

“Having ancient genomes is a valuable source of information, but it has to be used very wisely,” Boeckx says. “There isn’t a direct link between genotype and phenotype.”

Without experimental evidence, such as gene-function studies in model organisms, the cognitive effects of these mutations remain speculative. But Boeckx agrees that highlighting subcortical areas broadens the conversation about hominin cognition beyond the cerebral cortex.

From Genes to Technologies

Even with caveats, Lombard’s approach underscores how internal brain circuitry may have supported the outward behaviors archaeologists study. If attention networks in Homo sapiens became more robust, they could have enabled longer periods of focus, finer motor control, or more elaborate social coordination. Lombard’s previous work has already identified 48 attention-related genes expressed differently in the precuneus, a region associated with self-awareness and spatial reasoning.

As Lombard notes, these hidden aspects of the brain may hold the keys to understanding why Homo sapiens produced complex symbolic traditions, long-range trade, and intricate toolkits, while other hominins faded.

“The goal,” Lombard explains, “is to assess these brain areas’ potential for telling us something new about how the human mind evolved its capacity for paying attention.”

Related Research

Gunz, P., et al. (2019). Neandertal introgression sheds light on modern human brain evolution. Nature, 571(7763), 512–516. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1366-5

Kochiyama, T., et al. (2018). Reconstructing the Neanderthal brain using computational anatomy. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 6296. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24331-0

Neubauer, S., et al. (2018). The evolution of modern human brain shape. Science Advances, 4(1), eaao5961. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao5961

Lombard, M. (2025). Towards an archaeology of attention: A neuro-genetic exploration. Journal of Archaeological Science, 182(106344), 106344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2025.106344