A landscape that counts

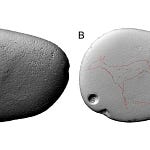

On a barren ridge above the Pisco Valley in southern Peru, a line of thousands of circular pits snakes across the earth like the scales of some buried serpent. The locals call the place Monte Sierpe—Serpent Mountain. From the air, it looks engineered, deliberate, almost coded: more than 5,000 holes, each a meter or two across, arranged in dense clusters and gaps that stretch for over a kilometer.

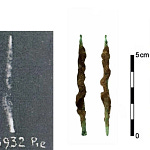

No one alive remembers why they were dug. Since Robert Shippee’s 1933 aerial photographs first appeared in National Geographic, the “Band of Holes” has invited wild speculation—storage pits, defense lines, alien landing sites. Now, a new study led by archaeologist Jacob Bongers and an international team of researchers in Antiquity1 reframes the riddle not as a mystery of aliens or warfare, but as one of numbers.

Their evidence suggests Monte Sierpe may have been part of an Indigenous accounting and exchange system—an enormous, open-air ledger where goods were stored, counted, and perhaps even taxed.

“Monte Sierpe blurs the boundary between architecture and abstraction,” says Dr. Elena Rossi, a paleoarchaeologist at Cambridge University. “It’s both a physical construction and a conceptual one—a landscape that records, in its own logic, the rhythms of exchange.”