The World Before Hunger

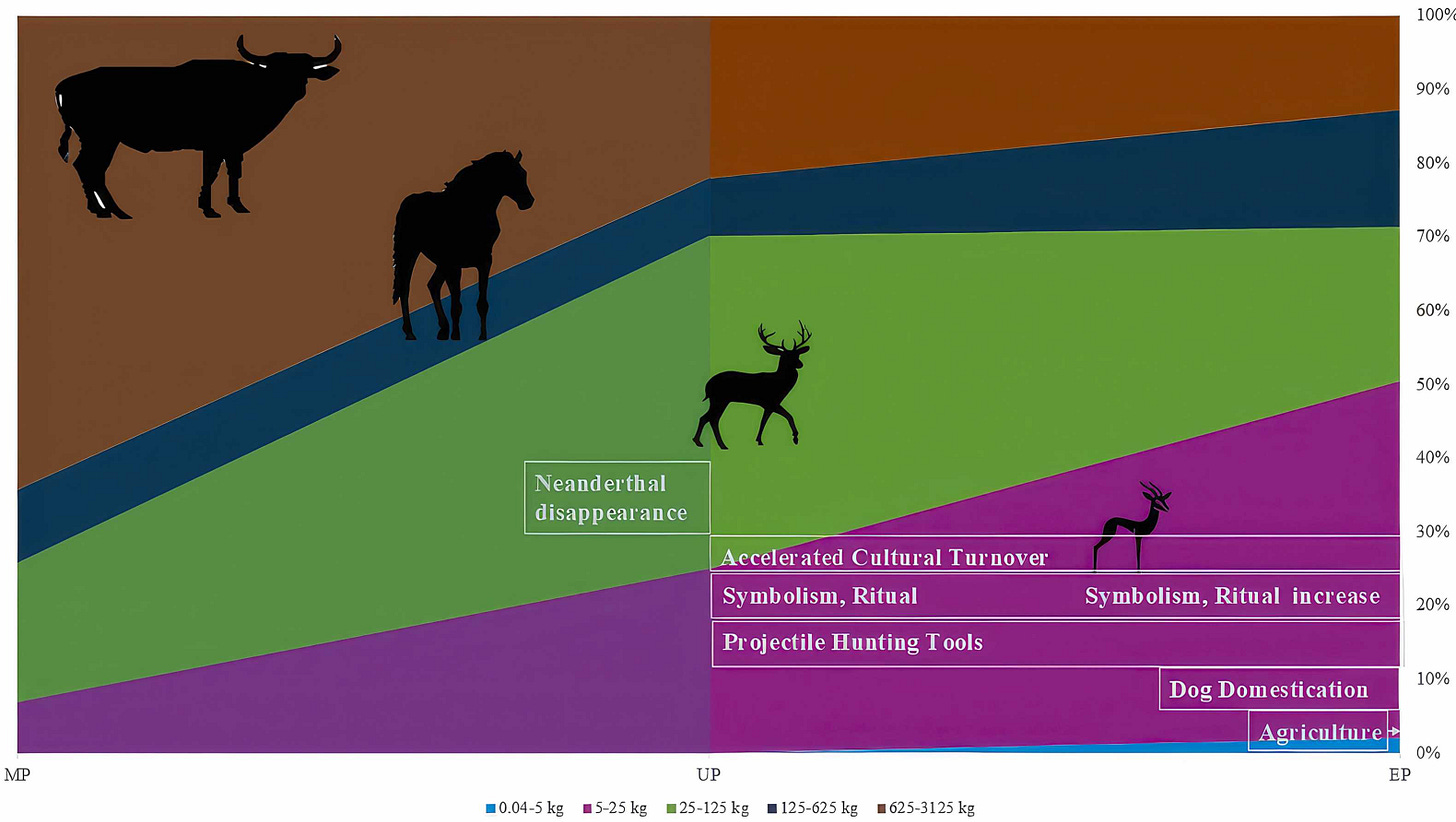

For nearly two million years, our ancestors lived in a world of abundance. Across Ice Age plains and forests, the land teemed with animals whose size defies imagination: woolly mammoths lumbering through the snow, aurochs grazing in herds, rhinoceroses built like tanks, and ground sloths as tall as giraffes. For Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, and later Homo sapiens, these massive creatures were both larder and landscape.

Big animals meant big returns. They provided fat-rich meat, marrow, and bone material for tools and fuel. The payoff was so high that early humans became specialized in hunting and scavenging large-bodied prey. But this specialization came with a hidden cost. When the great beasts vanished during the Late Quaternary Megafaunal Extinction, our species faced an unprecedented crisis of energy and adaptation.

That crisis, argue Israeli researchers Miki Ben-Dor and Ran Barkai in their 2025 study in Quaternary Environments and Humans,1 didn’t just shape our diet. It forged the modern human condition itself.

“The collapse of the megafaunal world was not simply an ecological event,” writes Dr. Mira Valenstein, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Haifa. “It was an evolutionary bottleneck that forced Homo sapiens to reinvent how to live, think, and cooperate.”