Across the rolling lowlands of southern Britain lie strange hills of bone and soil. They are not barrows or burial mounds but middens—prehistoric rubbish heaps built from the remnants of enormous communal feasts. New isotope research1 suggests these mounds were more than places to discard leftovers. They were hubs of mobility, identity, and social power at the end of the Bronze Age.

Middens as social landscapes

Middens are not subtle. Potterne in Wiltshire covers an area the size of five football pitches, its layers dense with charred bone and broken pottery. East Chisenbury rises like a long, low mound only ten miles from Stonehenge, holding the remains of hundreds of thousands of animals. At Runnymede, cattle bones dominate the soil near the Thames.

For decades, archaeologists suspected these accumulations reflected large-scale gatherings. Yet it was unclear just how far the people—or their livestock—had come to take part.

“Each midden had a distinct makeup of animal remains, with some full of locally raised sheep and others with pigs or cattle from far and wide,” explains Dr. Carmen Esposito, lead author of the new study, conducted at Cardiff University and now at the University of Bologna.

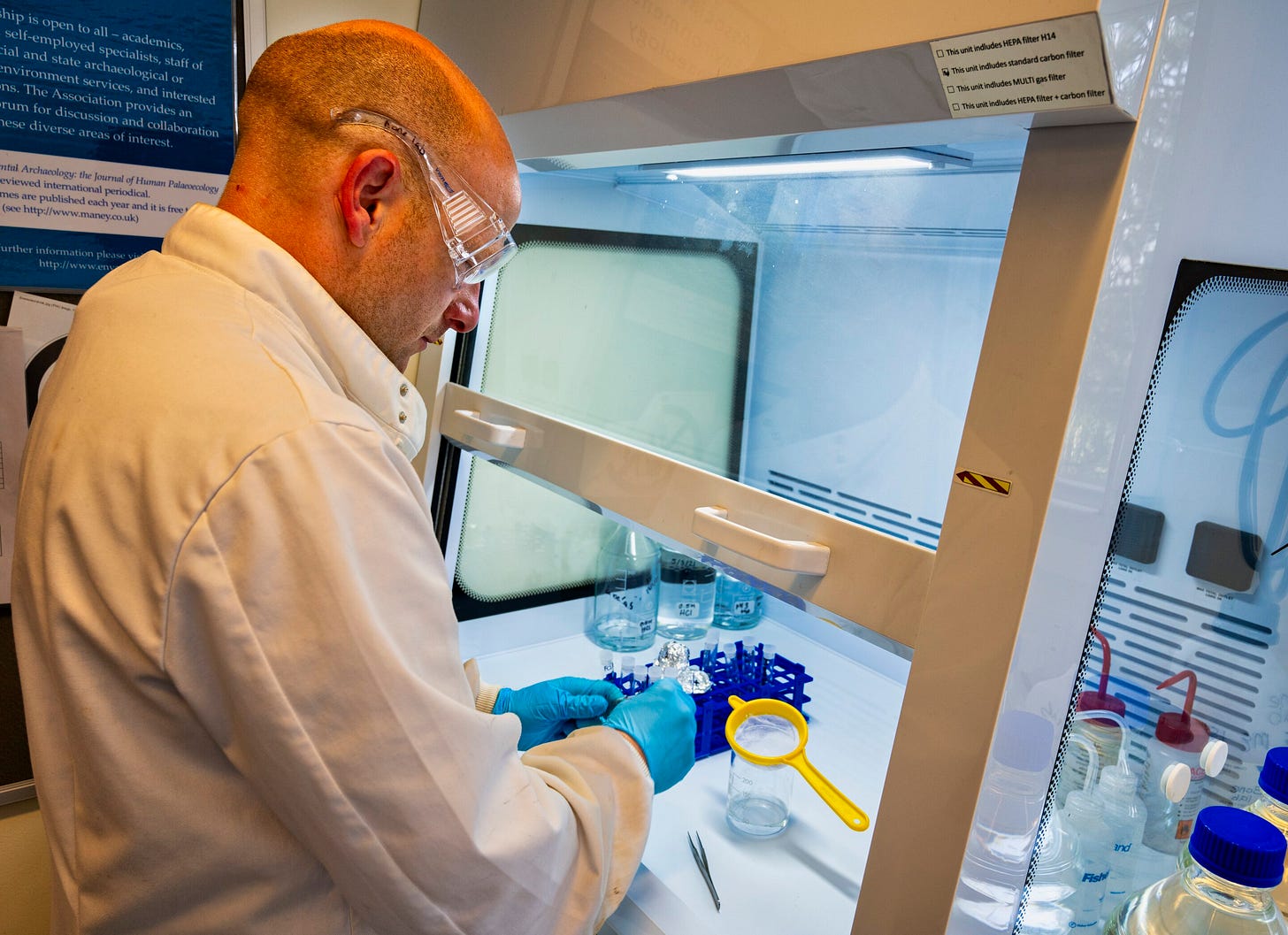

The research, published in iScience, examined six middens in Wiltshire and the Thames Valley. Using multi-isotope analysis, the team traced the geographic origins of the animals slaughtered at each site. The findings sketch a portrait of Bronze Age Britain in motion.

A feast of regions

Potterne stands out as a place of pork. Its pigs came from an unusually broad catchment, extending into northern England. This is not the signature of a single farm supplying meat, but of multiple groups converging on a shared ritual center.

Runnymede tells a different story. Here cattle, not pigs, dominate, and their isotopic signatures show origins far beyond the immediate region. East Chisenbury, in contrast, looks more local. Sheep form the overwhelming majority of bones, and the isotope values indicate animals raised in the surrounding landscape rather than imported from afar.

“We believe this demonstrates that each midden was a lynchpin in the landscape, key to sustaining specific regional economies, expressing identities and sustaining relations between communities during this turbulent period,” says Esposito.

The period in question—roughly 3,000 years ago—marked a time of upheaval. The value of bronze declined, trade networks shifted, and communities turned increasingly to farming. Yet the middens show that large gatherings persisted, perhaps becoming more important precisely because they helped knit fractured societies together.

Bones as travelogues

Multi-isotope analysis allows archaeologists to track animals across time and space. Because local geology leaves distinct chemical signatures in water, plants, and soil, those markers end up in the teeth and bones of animals and humans. Centuries later, researchers can use this geochemical map to identify where individuals were raised.

“At a time of climatic and economic instability, people in southern Britain turned to feasting—there was perhaps a feasting age between the Bronze and Iron Age,” says Professor Richard Madgwick, a co-author of the study at Cardiff University.

These events were not merely about consumption. They created obligations and alliances, forged identities, and reaffirmed social structures. The middens themselves became monuments—physical testaments to gatherings that may have rivaled anything seen again in Britain until medieval fairs.

“The scale of these accumulations of debris and their wide catchment is astonishing and points to communal consumption and social mobilization on a scale that is arguably unparalleled in British prehistory,” Madgwick adds.

Beyond the Bronze Age

The study complicates earlier ideas of an isolated and fragmented Late Bronze Age. Instead, it shows a patchwork of interconnected communities, each using feasting to anchor social and economic networks. Potterne, Runnymede, and East Chisenbury were not interchangeable—they played complementary roles in a wider system of movement, trade, and ritual.

These findings also underscore how material discarded thousands of years ago can retain vital information. In the bones of pigs and sheep lie stories of human travel, social cohesion, and the shifting meaning of meat at a pivotal moment in Britain’s past.

Related Research

Madgwick, R., Lamb, A. L., Sloane, H., Nederbragt, A. J., Albarella, U., & Parker Pearson, M. (2019). Multi-isotope analysis reveals that feasts in the Stonehenge environs involved livestock from across Britain. Science Advances, 5(3), eaau6078. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau6078

Parker Pearson, M. (2012). Stonehenge: Exploring the Greatest Stone Age Mystery. Simon & Schuster.

Sharples, N., & Parker Pearson, M. (1997). Between Land and Sea: Excavations at Dun Vulan, South Uist. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Esposito, C., Madgwick, R., Serjeantson, D., Garrow, D., Needham, S., Parker Pearson, M., & Sharples, N. (2025). Animal bones found in Late Bronze Age rubbish heaps show the distances people traveled to feast. iScience, 41, 113271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.113271