Bones that Remember the Sea

At first glance, the bone fragments from Fais Island looked like the detritus of a meal long finished: pale vertebrae, the faint curvature of spines, each one a whisper from a vanished ocean world. But within those bones, hidden in the resilient coils of collagen, scientists found a memory—a molecular record of what Pacific islanders caught, ate, and depended upon for nearly two millennia.

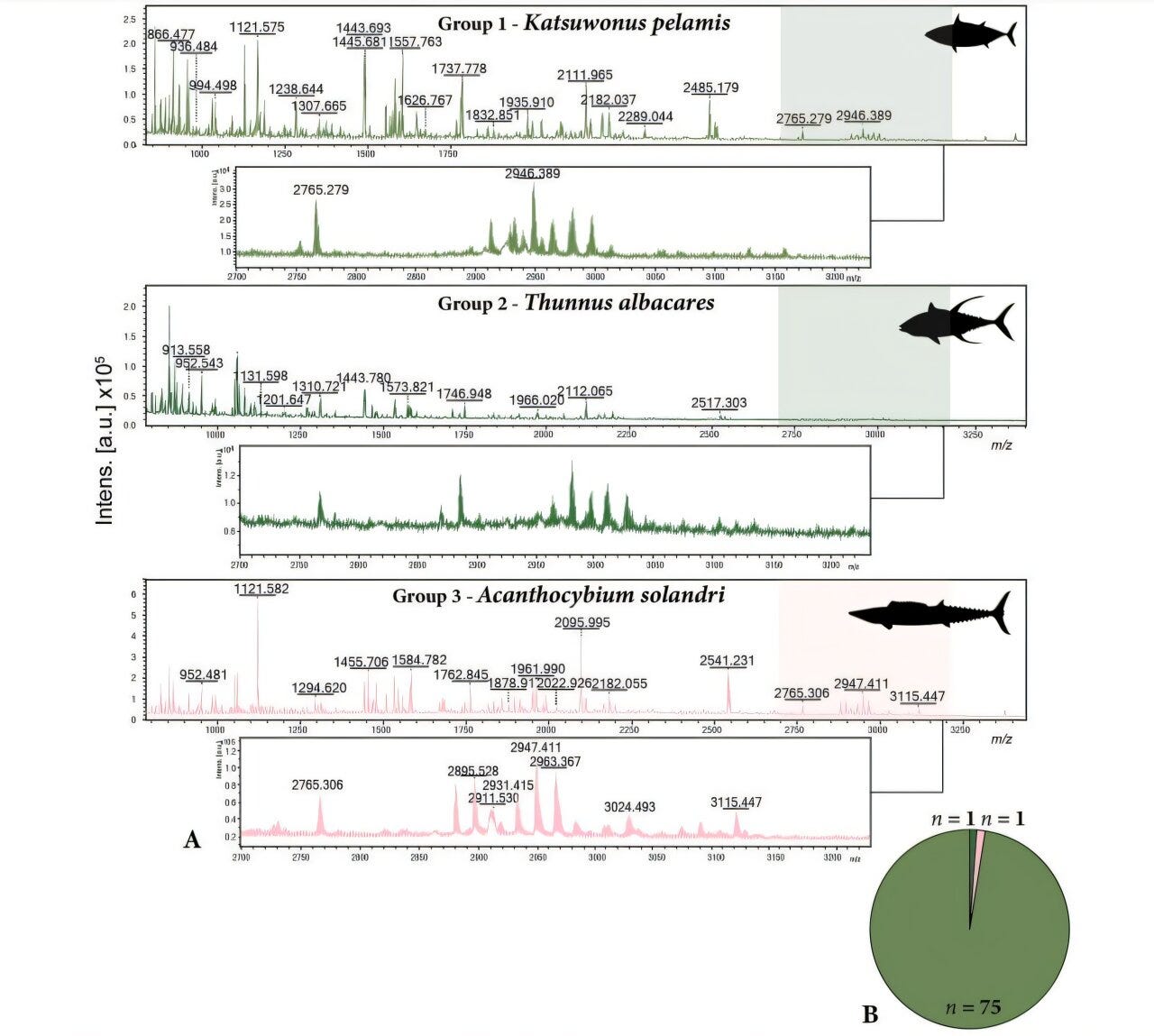

In a recent study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science,1 Clara Boulanger of University College London and her colleagues Rintaro Ono, Michiko Intoh, and Michael Buckley used a technique called Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS) to analyze these ancient remains from the small Micronesian island of Fais. The method allowed them to chemically identify species from collagen—the fibrous protein that can survive in bone long after DNA has faded.

Their analysis paints a vivid picture: the prehistoric inhabitants of Fais were not merely coastal fishers casting nets over reefs. They were skilled mariners capable of venturing into the open ocean, targeting some of the fastest, most elusive predators in the sea—tunas and sharks.

“Collagen acts like a fingerprint left by evolution,” explains Dr. Marisa Tano, a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Queensland. “When the shapes of bones fail to tell species apart, collagen’s molecular code still remembers.”