The Water That Remembered Time

Five thousand years ago, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers met the edge of the Persian Gulf, the world’s first cities began to rise. Uruk. Lagash. Eridu. Each was born in a landscape that seemed to breathe—the land swelling and falling twice a day as tides surged inland from a Gulf that extended far beyond its modern reach.

For generations, historians credited human mastery of irrigation for transforming these floodplains into the birthplace of civilization. But a new study by Liviu Giosan of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Reed Goodman of Clemson University argues that the story began long before canals and kings. Their work, published in PLOS ONE (2025),1 suggests that the Sumerians were, quite literally, a tidal people.

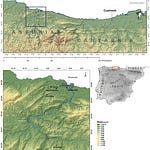

Using high-resolution satellite mapping and a 25-meter sediment core from the ancient city of Lagash, Giosan and Goodman reconstructed a vanished coastline. Their findings reveal that early Sumer was shaped by the rhythms of an estuarine world—one where daily tides irrigated the land naturally, creating a self-sustaining agricultural system that laid the foundation for urban life.

“Sumer was not simply carved from the desert by human ambition,” says Dr. Reed Goodman. “It was coaxed into being by the gentle persistence of tides that turned barren plains into living soil.”