The Cave That Watched History

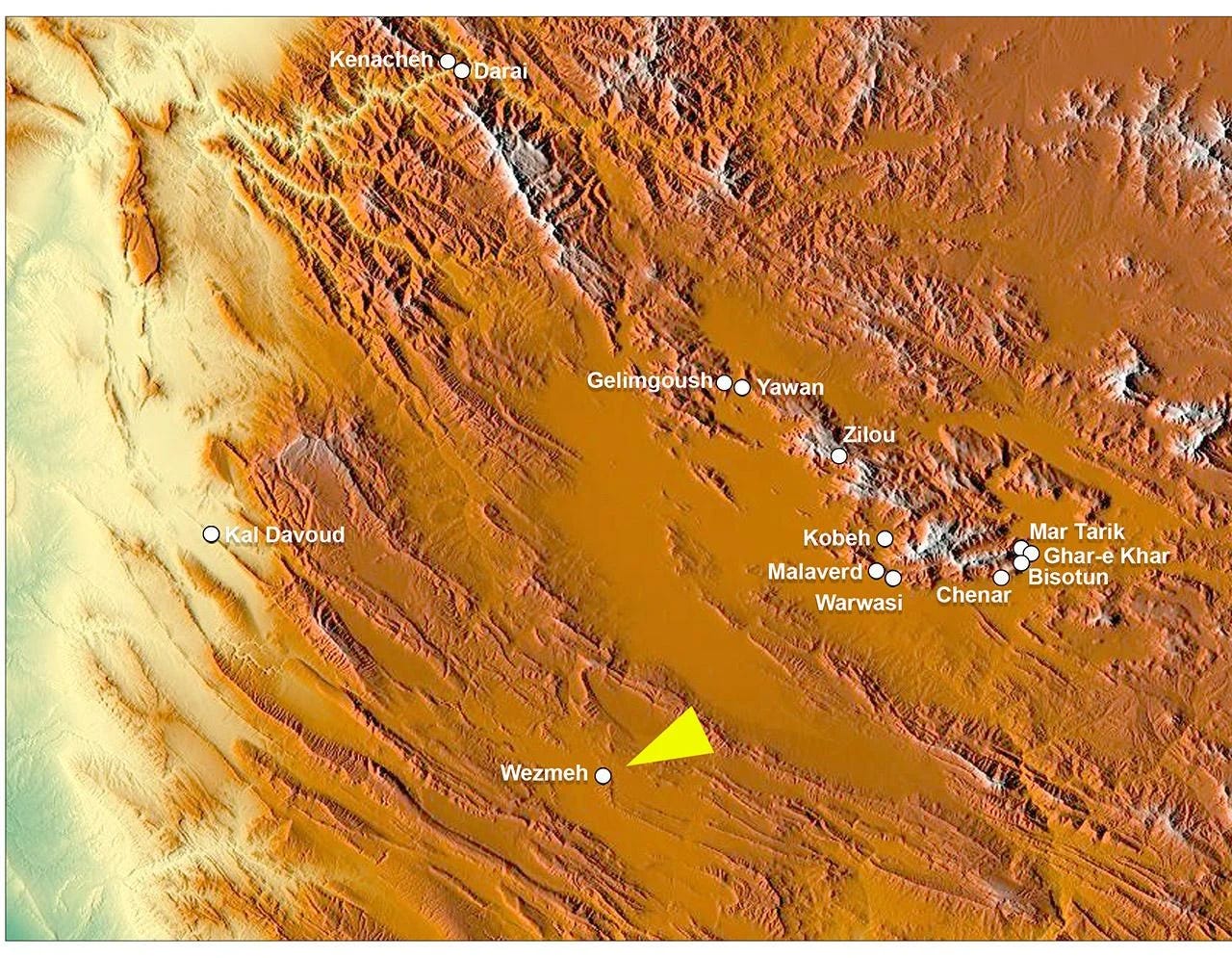

Tucked into the western flank of Iran’s Zagros Mountains, Wezmeh Cave has long been a quiet witness to the drama of ecological and human history. Near the modern city of Kermanshah, this limestone chamber once echoed with the footsteps of bears, hyenas, Neanderthals, and eventually early herders.

Now, after more than a decade of sporadic excavation, the cave is offering a vivid picture1 of environmental transformation and long-term human-animal interaction in a rugged corner of the Iranian Plateau. A 2019 field season led by archaeologist Fereidoun Biglari, Iran’s National Museum, recovered more than 11,000 well-preserved animal bones—making Wezmeh one of the richest prehistoric faunal sites in Western Asia.

“From large carnivores to domesticated livestock, the variety of species at Wezmeh is unmatched on the Iranian Plateau,” said Dr. Hossein Davoudi, zooarchaeologist at the University of Tehran.

The research team includes Dr. Marjan Mashkour, a CNRS and University of Tehran scholar whose career has been spent tracing the relationship between ancient humans and animals across Southwest Asia. Together, the team has begun to reconstruct a detailed ecological history—one bone fragment at a time.

Lions, Hyenas, and Herders

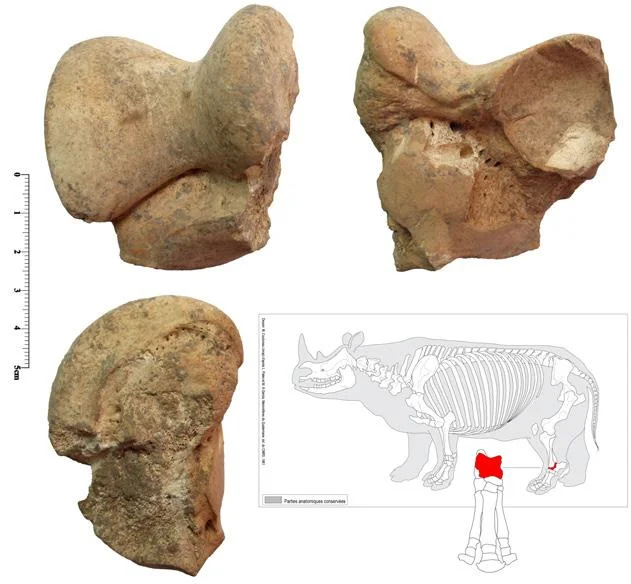

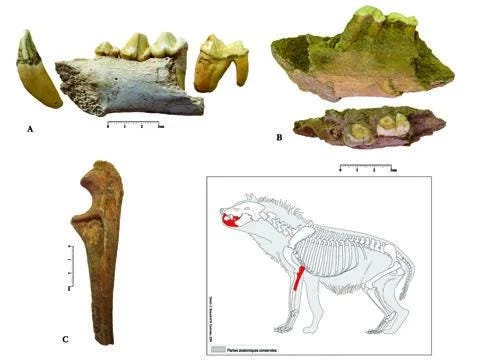

The bones tell a story spanning tens of thousands of years. Some belonged to extinct megafauna, like Panthera spelaea (the Eurasian cave lion) and Crocuta crocuta spelaea (the spotted hyena), once roaming the Pleistocene steppe. Other specimens point to later intrusions: domesticated sheep (Ovis aries) and goats (Capra hircus), likely brought by early Neolithic pastoralists.

“The cave was alternately a predator’s den, a death trap, and a human shelter,” said Dr. Mashkour. “But what makes it stand out is how well the faunal succession mirrors both climate change and cultural shifts.”

The team’s findings show how human presence was intermittent, but meaningful. Some bones display burning, while others are butchered or fractured in ways that suggest food processing. Small hearth features and domestic faunal remains point to episodic use of the cave during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic—by people who herded animals, gathered plants, and perhaps sought shelter during seasonal migrations.

And Wezmeh isn’t just an animal story. Earlier excavations uncovered the fossilized premolar of a Neanderthal child, as well as Early Neolithic human remains—revealing that hominins of more than one kind once passed through this sheltering space.

A Rare Look at a Changing Plateau

Today, Kermanshah is semi-arid and sparsely wooded. But buried beetle fragments and savannah animal bones from Wezmeh suggest a far different past—one in which the region was wetter, greener, and capable of supporting a diverse array of large herbivores.

This makes Wezmeh more than just an archaeological site; it’s a paleoenvironmental archive. Its long stratigraphy offers insight into how species—and humans—responded to fluctuating climates in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene. The cave's faunal record aligns with other key Zagros sites but stands out for its sheer breadth and state of preservation.

“Wezmeh is not just a list of species. It’s a narrative of adaptation, resilience, and ecological change,” said Dr. Biglari. “Its continuous occupation from the Middle Paleolithic to the early Holocene makes it an unparalleled resource for studying deep-time human-animal dynamics.”

Why It Matters

Sites like Wezmeh are rare. In regions where preservation conditions are often poor, finding a dense and chronologically deep record of animal life is invaluable. For anthropologists and archaeologists, the bones are clues—not just to what animals lived where, but to how ancient humans adapted, hunted, herded, and moved across the Zagros.

The discovery also serves a broader purpose. As the Middle East faces intensifying ecological stress today, understanding how ancient peoples responded to environmental shifts could shed light on strategies for future resilience.

Related Research and Further Reading

Bailey, G. N., & King, G. C. P. (2011). Dynamic Landscapes and Human Evolution: The Case for Africa. Quaternary Science Reviews, 30(11-12), 1313–1331.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.01.017Zanolli, C., Biglari, F., Mashkour, M., Abdi, K., Monchot, H., Debue, K., Mazurier, A., Bayle, P., Le Luyer, M., Rougier, H., Trinkaus, E., & Macchiarelli, R. (2019). A Neanderthal from the Central Western Zagros, Iran. Structural reassessment of the Wezmeh 1 maxillary premolar. Journal of Human Evolution, 135, 102643.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102643Zeder, M. A. (2012). The Broad Spectrum Revolution at 40: Resource diversity, intensification, and an alternative to optimal foraging explanations. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 31(3), 241–264.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2012.03.003

Davoudi, H., Mashkour, M., & Biglari, F. (2025). Prehistoric animal remains in Iran’s Wezmeh Cave reveal Zagros biodiversity. Journal of Iran National Museum, 4(1), 43–53.

https://jinm.irannationalmuseum.ir/article_720756.html?lang=en