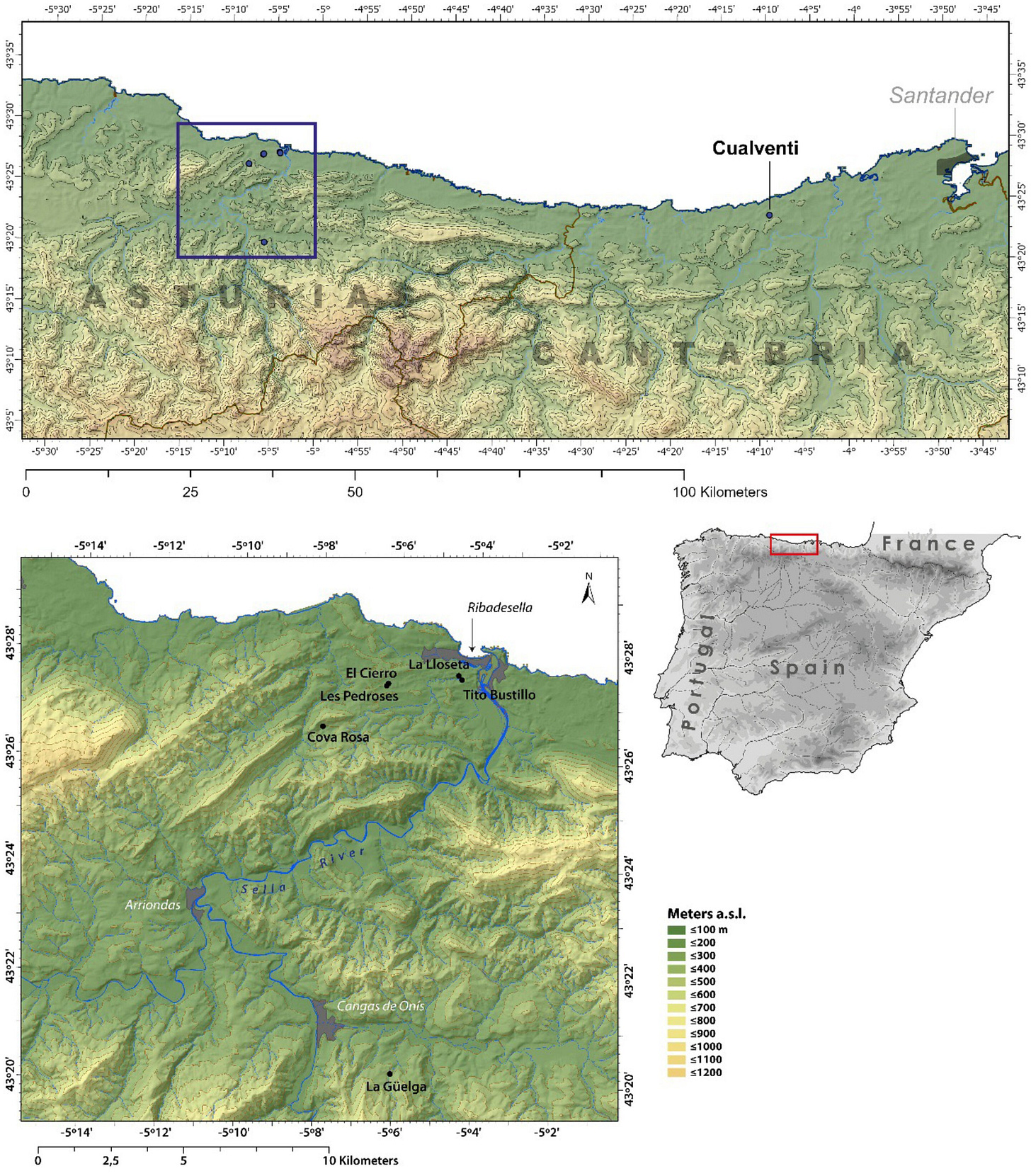

Along the rocky shore of northern Iberia, 18,000 years ago, people moved between caves, river mouths, and tidal flats with a practiced familiarity. They hunted red deer in the hills and pried limpets from stone. They gathered periwinkles by the handful. They carried shells back to caves like Tito Bustillo, where hearths glowed, tools were sharpened, and walls were marked with images that still command attention today.

For decades, archaeologists have used those shells to anchor the timing of this coastal life. But shells are tricky witnesses. The ocean runs on a different carbon clock than the land. Now, a new study1 shows just how much that difference matters and why even the species of shell can tilt the calendar by centuries.

The work, led by Asier García-Escárzaga and colleagues, does not rewrite the story of the Magdalenian in northern Spain. What it does is sharpen it. By combining Bayesian modeling with paired marine and terrestrial samples from Tito Bustillo Cave, the team has produced more precise local correction factors for marine radiocarbon dates. The result is a tighter, more reliable timeline for a critical phase of European prehistory, and a reminder that the smallest details, down to which mollusk ended up in the fire, can ripple through big narratives.