The First Truly Global Material

Stone, bronze, and iron all defined earlier chapters of human history, but they emerged regionally and spread unevenly across the globe. Plastic is different. It appeared almost everywhere at once in the mid-20th century. By the 1950s, plastics had entered households from São Paulo to Shanghai, joining the fabric of daily life with astonishing speed.

A new study in Cambridge Prisms: Plastics1 contends that plastics are more than an environmental crisis — they’re also the defining material of a new archaeological era.

“It is easy to view plastics as a toxic legacy and the cause of environmental harm, which — of course — they are,” explains Professor John Schofield of the University of York. “But as archaeologists, we can also view them from another angle entirely — as a valuable archive that documents human impacts on planetary health.”

Reading an Archive Made of Waste

Unlike pottery sherds or bronze blades, plastic artifacts are still largely in circulation. Yet every bottle cap, bag, or synthetic fiber that moves from use to discard leaves a material trace, one that can persist far longer than the societies that produced it. Microplastics now drift in the stratosphere, sink to the ocean floor, and lodge in soils, plants, and human tissue.

The research team argues that this diffusion turns plastics into a kind of global stratigraphic marker — a future “layer” of our planet’s crust.

“Plastics are everywhere — from the deep ocean to high mountains — so are ubiquitous, resilient, and toxic as they continually break down, eventually to nanoscale,” Schofield notes. “We question how society should view an archaeological record that represents such a valuable archive documenting activities and behaviors at a crucial time in human history, while at the same time being a dangerous contaminant.”

The Archaeology of Us

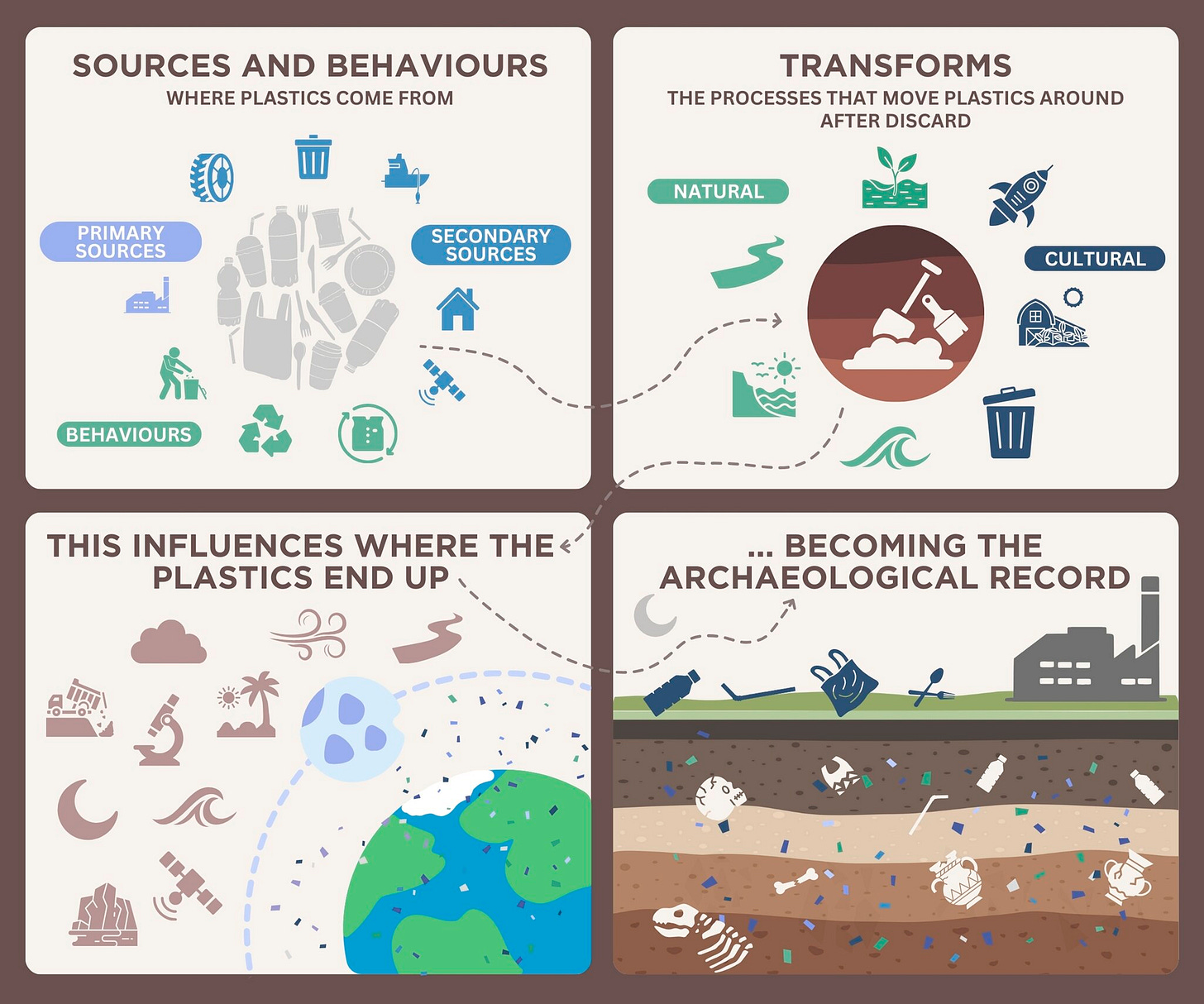

Archaeology has long concerned itself with the deep past, but in recent years it has widened its scope to contemporary material culture — a field some scholars call the “archaeology of us.” The Schofield team places plastics squarely within this movement, proposing that archaeologists track not only the accumulation of plastics but also their journeys from production to discard.

Professor Alice Gorman of Flinders University, a co-author on the study, emphasizes that this archive extends beyond Earth.

“Our aim is to show how plastics are more than just pollution — they’re a record of human behavior in the contemporary world that extends from the deepest oceans to the furthest reaches of the solar system, everywhere that spacecraft have traveled. There are even plastics on the moon.”

A Planet-Wide Era

Unlike the Bronze Age or Iron Age, the so-called “Plastic Age” began nearly simultaneously worldwide. It is enmeshed with larger planetary processes — fossil fuel extraction, industrialization, mass consumerism, and climate change. The researchers point out that this synchronicity makes plastics unique as a marker of human activity.

The study also suggests practical steps. By identifying the point at which plastics transition from use to discard, archaeologists could help inform interventions to reduce pollution and conserve ecosystems.

What Future Archaeologists Might Find

If archaeologists 10,000 years from now dig through 21st-century sediments, they will find traces of how humans ate, traveled, dressed, and built their lives — all through synthetic polymers. In much the same way ancient refuse heaps reveal diets and trade networks, our discarded plastic will map our cities, migration, and economies.

Schofield and colleagues see this record as both a warning and an opportunity: an archive of our impact and a guide to how future generations might understand — or mitigate — what we have left behind.

“We need this archive, both to help us understand and try to reduce our impacts now, but also to ensure people can understand these impacts in the future,” Schofield says.

Related Research

Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Williams, M., & Summerhayes, C. (2019). The Anthropocene as a geological time unit. Nature, 573(7773), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0338-4

Ford, A., & Clarke, A. (2019). “The archaeology of the contemporary past.” Annual Review of Anthropology, 48, 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102218-011318

orman, A. C. (2020). Dr Space Junk vs The Universe: Archaeology and the Future. MIT Press.

Turner, A., & Arnold, R. (2018). “Plastics in the archaeological record.” Environmental Archaeology, 23(2), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2016.1260087

Schofield, J., Gorman, A., Antonello, A., Couceiro, F., Leterme, S., MacGregor, M., Snigirova, A., & Werner, A. D. (2025). Archaeological and systemic context for the plastic age: Theorising the formation of contemporary and future archaeological records. Cambridge Prisms: Plastics, 3(e33), e33. https://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2025.10028