The Silent Clues at the End of the Radius

For more than a century, reconstructions of early human movement have leaned heavily on bones. Limb proportions, joint surfaces, and muscle attachment scars have served as the standard evidence for deciding whether an ancestor walked upright, climbed trees, or did both with ease. This approach has delivered major insights into the evolution of bipedalism and manual dexterity in Homo sapiens and its relatives.

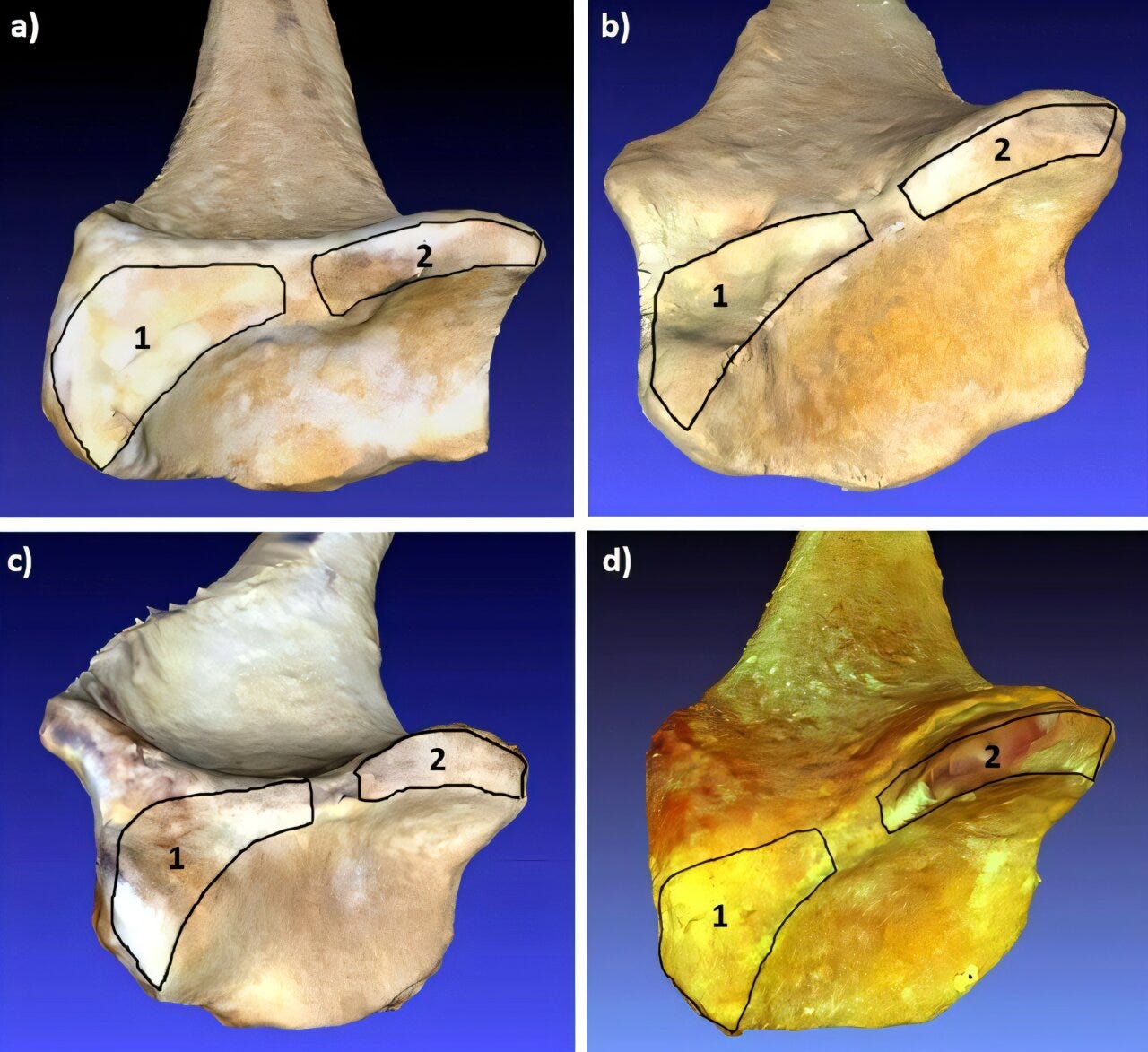

But bones do not work alone. Every movement is stabilized and constrained by ligaments, the dense bands of connective tissue that tether bones to one another and quietly dictate how joints behave under stress. Ligaments almost never fossilize. What does survive, however, are the subtle landscapes where they once anchored themselves to bone.

A recent study in Scientific Reports1 argues that these landscapes deserve far more attention. By examining the insertion sites of wrist ligaments on fossil radii using three dimensional geometric morphometrics, researchers propose a new way to infer how ancient hominins balanced climbing, walking, and manipulating objects.

The wrist, long treated as a secondary player in locomotor debates, suddenly takes center stage.