The tropical rainforest is an engine of decomposition. Acidic soils strip flesh from bone, and humidity rots wood to mulch, leaving the archaeological record of Central Africa frustratingly blank. To understand the humans who navigated these dense canopies thousands of years ago, researchers often have to look for geological lucky breaks.

Pahon Cave is one such anomaly. Located in the dolomitic rock formations of Lastoursville, Gabon, this massive cavern—with ceilings soaring over 20 meters—has acted as a protective vault. Protected by stable layers of bat guano and sediment, the cave floor preserved a record of human occupation spanning roughly 5,000 years, from the Middle to the Late Holocene.

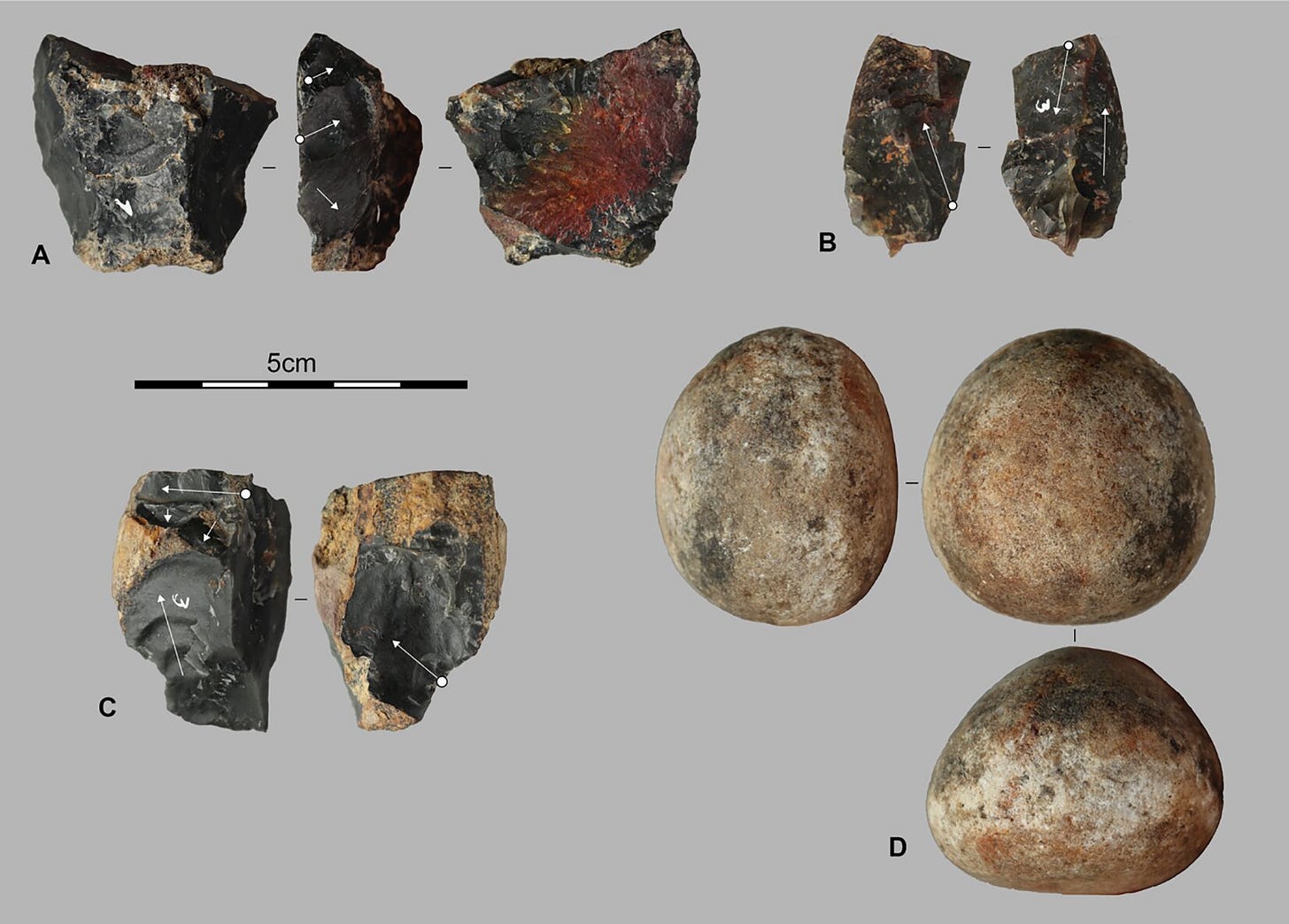

A recent study published in PLOS One1 details the findings from two excavation trenches within Pahon Cave. The team, led by Marie-Josée Angue Zogo, recovered over a thousand stone artifacts and animal bones. But what they found—or rather, what they didn’t find—challenges the standard narrative of technological progress. In a period marked by dramatic climatic shifts and the migration of new people groups across the continent, the occupants of Pahon Cave seemingly refused to change their toolkit. They found a method that worked, and they stuck to it for five millennia.