An Ancient Puzzle Hidden in a Book of Bark

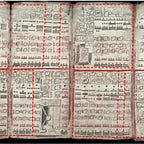

More than a thousand years ago, deep in the rainforests of Mesoamerica, Maya scribes inked a mysterious series of numbers and glyphs onto folded sheets of bark paper. The resulting document, now known as the Dresden Codex, would one day travel across an ocean to Europe, survive war and fire, and eventually find itself scrutinized by modern astronomers and mathematicians alike.

The Codex’s most enigmatic feature is a table spanning 405 lunar months—roughly 32 years—filled with numerical sequences that align with the phases of the Moon and the timing of eclipses. For generations, scholars have puzzled over how these pre-Columbian astronomers managed to produce eclipse predictions with such uncanny accuracy, long before telescopes or trigonometry.

A new study by John Justeson of the University at Albany and Justin Lowry of SUNY Plattsburgh, published in Science Advances (2025),1 proposes an elegant answer: the Mayan eclipse table was not designed as a stand-alone chart for predicting celestial events but evolved from a more general lunar calendar that synchronized with the sacred 260-day divinatory calendar. By linking lunar cycles with ritual time, the Maya built an astronomical tool that remained accurate for centuries.

“What makes the Dresden Codex so extraordinary is not just its accuracy,” explains Dr. Laura Cardenas, an archaeoastronomer at UNAM. “It’s that the Maya achieved this precision by embedding mathematical reasoning within their ritual calendar system. Their science was inseparable from their cosmology.”