Science at the Request of the People

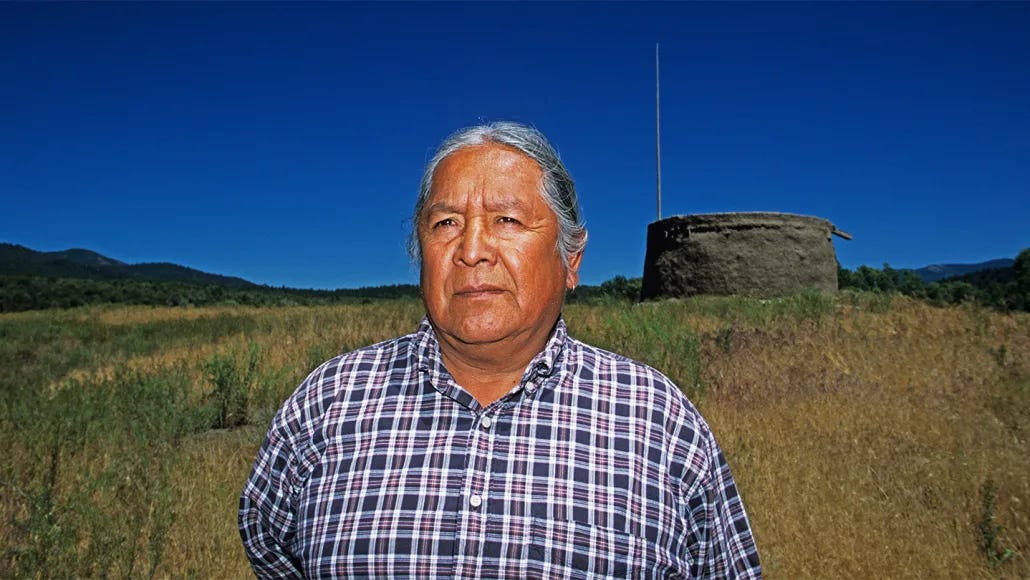

The sweeping desert of north-central New Mexico carries centuries of memory in its sandstone, canyons, and wind. In this landscape stands Picuris Pueblo—a small, sovereign tribal nation whose history has long been narrated in stories passed down through generations. These stories speak of migration, of belonging, of origins tied to Chaco Canyon, one of the great ceremonial and cultural centers of the ancient Puebloan world.

But these narratives have often been set aside or doubted in academic circles—dismissed as myth rather than memory. A new study, however, places them squarely in the realm of science.

Published in Nature1 on April 30, 2025, the research represents the first time a U.S. federally recognized tribe has led and co-authored a genomic study of its own ancestry. The study analyzed DNA from 16 ancient individuals buried at Picuris Pueblo (dating from 1300 to 1500 CE) and compared it to that of 13 current tribal members. The genetic signal was clear: a deep, continuous lineage ties modern Picuris people to Chaco Canyon’s inhabitants.

“Our elders knew we had always been here,” said Picuris Lieutenant Governor Craig Quanchello. “But it was very moving and powerful to see it validated on paper.”

This wasn’t science imposed from the outside. It was science requested by the people, designed to protect their past and inform their future.

Ancient Ties, Modern Stakes

The study grew from a desire not just to explore ancestry but to support sovereignty. Concerns over nearby oil and gas development around Chaco Canyon prompted Picuris leaders to seek data that might bolster their longstanding claims of connection to the site.

With guidance from Danish evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev and his team at the University of Copenhagen, the tribe carefully selected remains and participants. The goal: to trace lineage, not to probe identity. Consent, control, and co-authorship were non-negotiable.

The team discovered that ancient and present-day Picuris individuals form a distinct genetic cluster, more closely tied to ancestral Puebloan individuals from Chaco Canyon than any other known group. The connection includes maternal lines—transmitted through generations of women—highlighting the continuity of life and kinship through centuries of upheaval.

“This is life-changing data,” said Picuris Governor Wayne Yazza. “It’s not just about genetics—it’s about our story, our identity, and our right to be heard.”

The Collapse That Wasn’t

Archaeological theories have long held that Chaco Canyon’s abandonment around 1150 CE led to the region being vacated. Some suggested that the great houses emptied into oblivion, their builders lost to history. But the genomic evidence from Picuris contradicts that narrative.

Rather than vanishing, some Chacoan peoples may have resettled into smaller, more autonomous communities like Picuris. Genetic stability from 1300 onward suggests that rather than collapse, Chaco society diffused—perhaps intentionally—into the surrounding landscape.

Population estimates suggest around 3,000 individuals lived at Picuris during the late precontact period, maintaining a robust community well after Chaco’s ceremonial glow dimmed. It’s only after 1535, when Spanish colonial pressures intensified, that the Picuris population shows evidence of sharp decline—falling by roughly 85%.

A Model for Ethical Collaboration

The study represents a significant shift in how ancient DNA research is conducted. For decades, Native American communities were excluded from or even harmed by archaeological and genetic research. Bones were taken. Burial grounds disturbed. Oral traditions ignored.

This time, the power dynamic was reversed. The questions came from within the community. The methodology was approved by tribal councils. The interpretation was shaped by cultural context.

“This research is a landmark project,” said archaeologist David Hurst Thomas of the American Museum of Natural History. “It’s the kind of work that should become standard.”

This is not just about science. It is about whose voice defines the past, and whose memory counts.

Listening to Memory

The Picuris findings do not deny the ancestral claims of other Pueblo peoples connected to Chaco Canyon. Rather, they confirm one piece of a larger, interwoven story—one told not only in genes and stones but in songs, stories, and ceremonies.

For Indigenous communities, oral tradition is not metaphor. It is record.

“We’ve been telling our stories since time immemorial,” said Quanchello. “Now science is catching up.”

As debates over the future of Chaco Canyon intensify, including disputes over drilling and land use, these findings may offer more than a scientific footnote. They may serve as legal and cultural reinforcement of Indigenous stewardship.

Related Research

Pinotti, T., et al. (2025). Picuris Pueblo oral history and genomics reveal continuity in US Southwest. Nature, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08791-9

Reich, D. (2018). Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Pantheon.

Snow, D. R. (2010). Archaeology of Native North America. Prentice Hall.

Dombrowski, K. (2001). Against Culture: Development, Politics, and Religion in Indian Alaska. University of Nebraska Press.

Kuklick, H. (1991). The Savage Within: The Social History of British Anthropology. Cambridge University Press.

Pinotti, T., Adler, M. A., Mermejo, R., Bitz-Thorsen, J., McColl, H., Scorrano, G., Feizabadifarahani, M., Gandy, D., Boulanger, M., Gaunitz, C., Stenderup, J., Ramsøe, A., Korneliussen, T., Demeter, F., Santos, F. R., Vinner, L., Sikora, M., Meltzer, D. J., Moreno-Mayar, J. V., … Willerslev, E. (2025). Picuris Pueblo oral history and genomics reveal continuity in US Southwest. Nature, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08791-9