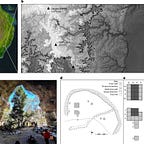

By the time snow blanketed the Blue Mountains during the height of the Last Glacial Maximum, much of Australia's high country was thought to be too harsh for human habitation. Barren ridgelines, sub-zero winters, and frozen water sources seemed like insurmountable barriers to Ice Age foragers. But recent excavations1 at a rock shelter known as Dargan, perched more than 1,000 meters above sea level in the upper Blue Mountains, are telling a different story.

A Shelter in the Storm

Located on Dharug Country, Dargan Shelter might easily escape notice amid the eucalyptus-clad ridgelines of New South Wales. But within its walls lies evidence of a sustained and surprisingly early human presence at high elevation. Radiocarbon dating places the oldest occupation layer between 22,000 and 20,000 years ago, squarely within the Last Glacial Maximum, when average temperatures were at least 8 degrees Celsius colder than today. This makes Dargan the earliest securely dated Ice Age occupation site above 1,000 meters in Australia.

"This evidence requires a paradigm shift in our understanding of Australia’s mountains as a barrier to human mobility," write the authors of the study, published in Nature Human Behaviour.

Archaeologists uncovered 693 stone artifacts, including flaked tools made from both local claystone and non-local materials. Among them were flakes traced to sources as far away as Jenolan, 50 kilometers to the south-west, and the Hunter Valley, 150 kilometers to the north. Such finds suggest not just resilience but connectivity—people were moving through these ranges during the harshest climatic conditions of the Pleistocene.

Living Above the Tree Line

During the Last Glacial Maximum, the treeline in this region sat about 400 meters lower than the shelter's elevation. The site would have looked more like tundra than forest. Pollen records show no evidence of local trees, and firewood would have been scarce. Yet hearths dot the site: charcoal-rich layers, ash, and reddened sediments confirm repeated fire use despite these constraints.

"This wasn’t a one-off visit. People returned to this site throughout the glacial period," says Dr. Amy Way, lead archaeologist on the project.

The excavation revealed a continuous stratigraphic sequence, with artifact density peaking between 18,000 and 16,000 years ago. Later layers show gradual reforestation and increasing availability of firewood, aligning with the end of the glacial period and transition to warmer conditions.

Tools, Travel, and Adaptation

Among the finds was a sandstone grinding slab dated to around 13,200 years ago, with wear patterns consistent with the shaping of bone or wooden tools. Another artifact, a basalt anvil, was used to crack open nuts or seeds, reflecting subsistence strategies tailored to highland environments.

Strikingly, the types of stone and flaking techniques changed little over time. Raw material choices, flake sizes, and retouch rates remained stable despite dramatic shifts in climate and vegetation. This technological conservatism, alongside strategic adaptation to seasonal resource availability, paints a picture of people who knew how to live in marginal environments without reinventing their toolkit.

A Place Between Worlds

Dargan Shelter sits near a known Aboriginal travel route along the Bell's Line of Road ridgeline. Oral traditions and archaeological parallels suggest it was more than just a survival outpost—it may have been a ceremonial waypoint or social nexus. Rock art, including child-sized hand stencils and faded forearm images, point to its cultural significance. Today, members of the Wiradjuri, Dharug, Gundungara, and other groups maintain ancestral ties to this region.

"Dargan likely served as a meeting point between groups from the coast, the interior, and the surrounding ranges," the authors propose.

Rewriting a Continent's Story

Until now, archaeologists believed that sustained occupation of Australia's high country only began in the Holocene, well after the Ice Age. The Dargan excavation upends that timeline, joining recent discoveries from Ethiopia, Spain, and the Americas showing that high-elevation living was more widespread during the Pleistocene than previously thought.

This adds a critical chapter to Australia's human story, where ancestral knowledge and adaptability converge in a landscape once thought uninhabitable. Far from being a marginal space, the upper Blue Mountains emerge as a core zone of Ice Age activity, mobility, and memory.

Related Research

Ossendorf, G. et al. (2019). Middle Stone Age foragers resided in high elevations of the glaciated Bale Mountains, Ethiopia. Science, 365(6453), 583–587. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw8942

Ardelean, C. F. et al. (2020). Evidence of human occupation in Mexico around the Last Glacial Maximum. Nature, 584(7819), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2509-0

Alcaraz-Castaño, M. et al. (2021). First modern human settlement recorded in the Iberian hinterland occurred during Heinrich Stadial 2 within harsh environmental conditions. Scientific Reports, 11, 15161. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94282-2

Zhang, X. L. et al. (2018). The earliest human occupation of the high-altitude Tibetan Plateau 40,000 to 30,000 years ago. Science, 362(6418), 1049–1051. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat8824

Way, A. M., Piper, P. J., Chalker, R., Wilkins, D., Wilkins, E., Watson Redpath, L., Glass, P., Carroll, M. R., Nutman, E., Kononenko, N., Spate, M., Barrows, T. T., Wright, D., & Brennan, W. (2025). The earliest evidence of high-elevation ice age occupation in Australia. Nature Human Behaviour, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02180-y