The question of why modern humans eventually succeeded in leaving Africa, establishing global populations while earlier hominin migrations faded into oblivion, has puzzled scientists for decades. New research published in Nature1 offers a compelling clue: a massive ecological dress rehearsal that began nearly 70,000 years ago.

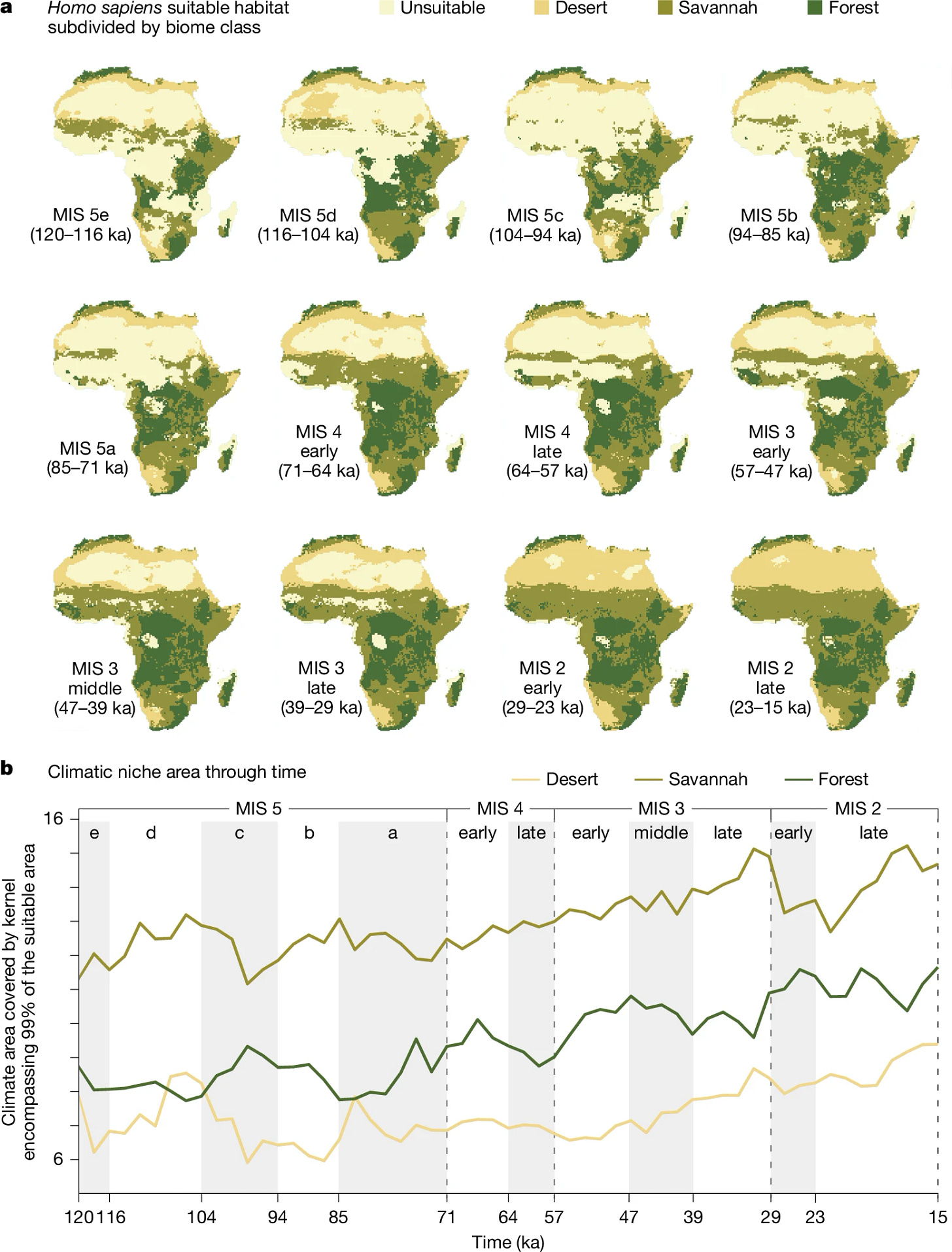

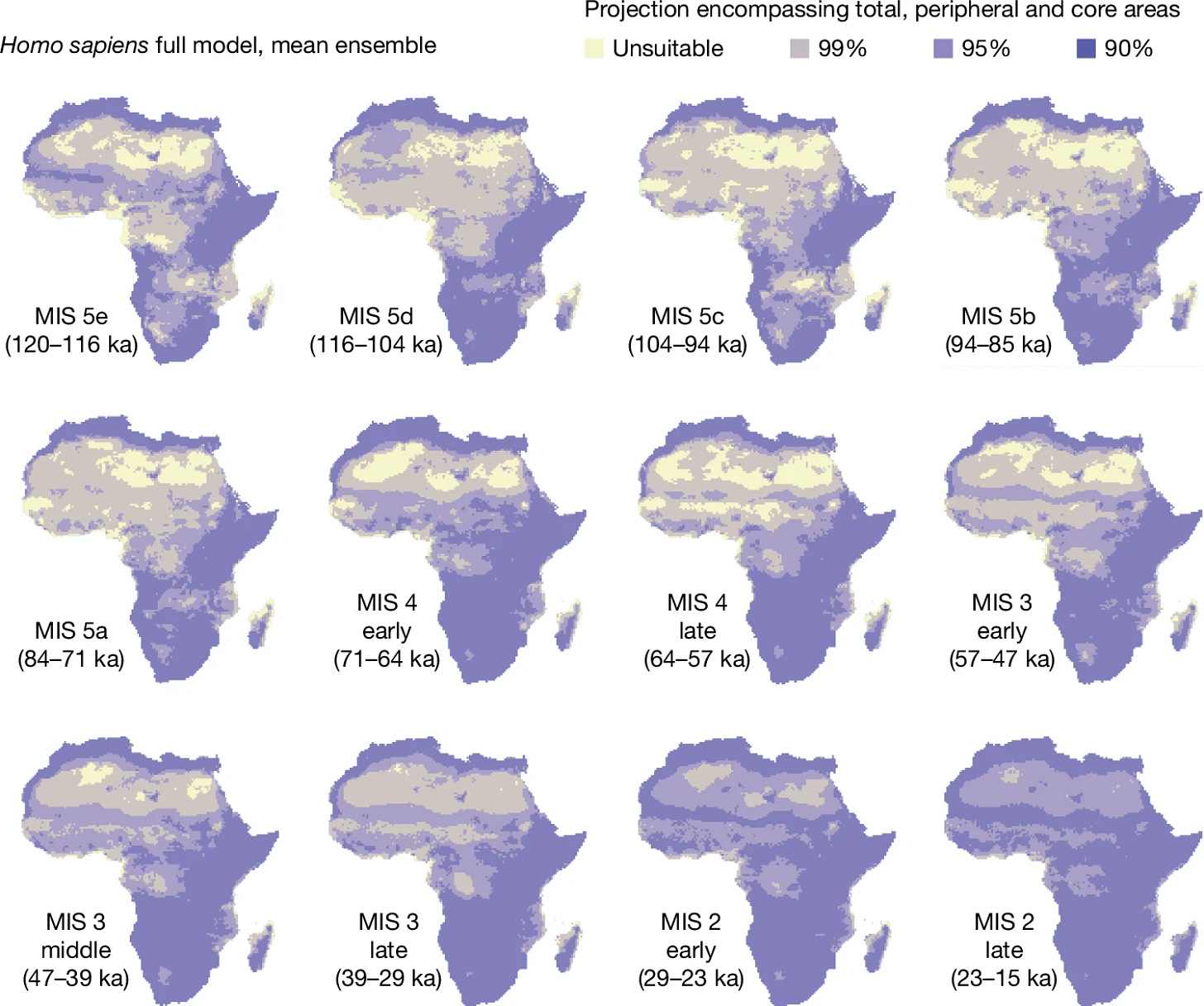

Led by Emily Hallett, Michela Leonardi, Andrea Manica, and Eleanor Scerri, the study pulls together hundreds of archaeological records from across Africa to chart how the habitats of Homo sapiens shifted over the past 120,000 years. Their results suggest that the ancestors of today's non-African populations were forged in the crucible of ecological experimentation across deserts, forests, and savannas.

"By 70,000 years ago, humans were not just surviving in familiar grasslands but pushing into dense rainforests and arid deserts," said co-author Eleanor Scerri. "This flexibility may be what finally enabled our species to move out of Africa and stay out."

The Climatic Catalyst: Shifting Grounds, Shifting Minds

Africa 120,000 years ago was a patchwork of biomes, shaped by monsoons, ice ages, and abrupt Heinrich events. During this time, Homo sapiens populations were relatively localized, sticking to environments like savannas with moderate rainfall and predictable resources.

That changed around 70,000 years ago. Environmental instability—particularly the onset of a colder, drier period linked to Heinrich Event 6—triggered both ecological fragmentation and opportunity. As lakes shrank and forests receded, humans found themselves navigating a continent in flux. The response was not retreat, but expansion into previously avoided environments.

Using species distribution models, the researchers showed that Homo sapiens began broadening their "niche"—a term ecologists use to define the range of environments a species can inhabit. By around 50,000 years ago, humans were occupying a dramatically expanded ecological range.

"We found a consistent pattern across two climate models: the human niche widened well before the dispersals into Eurasia. This was not a sudden leap, but a stepwise expansion into increasingly varied habitats," noted Andrea Manica.

From Forest to Desert: The Great Ecological Expansion

The study analyzed 479 radiometrically dated archaeological sites. These were mapped against paleoclimate simulations to reconstruct the climatic conditions humans experienced at different times.

Rather than a single breakthrough, the research points to a sustained period of innovation. Between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago, humans mastered life in West and Central African forests—places previously thought to be avoided due to dense vegetation and limited visibility. Simultaneously, they spread into the Saharan and Sahelian belts, which oscillated between wet and hyper-arid states.

"These areas weren’t necessarily high in population," said Michela Leonardi, *"but their occupation shows an ability to move between radically different ecosystems. That kind of mobility and versatility is key to the success of our species."

This expansion wasn’t simply a matter of better stone tools or symbolic thinking. Those traits had appeared in African populations tens of thousands of years earlier. Instead, it was ecological resilience—the ability to maintain foraging, hunting, and social cohesion in diverse habitats—that defined the ancestors of today's global population.

A Connected Continent

As populations became more mobile and adaptive, their networks likely expanded as well. The increased encounter rate between groups may have fostered cultural transmission and genetic mixing, setting the stage for the larger demographic wave that moved into Eurasia around 50,000 years ago.

"By then, you had a continent of generalists," Scerri explained. *"They weren’t just surviving. They were exchanging ideas, adapting locally, and learning to live in extreme environments."

These generalists weren’t large in number—arid zones still couldn't support high population densities. But they were nimble, persistent, and capable of jumping ecological boundaries, making them uniquely suited to the harsh climatic transitions that lay beyond Africa.

Echoes in the Record

The archaeological record mirrors these shifts. Around 60,000 to 50,000 years ago, evidence of long-distance exchange networks, ostrich eggshell water storage, ecosystem engineering through controlled burns, and dietary diversification appears across multiple African regions. These were not isolated innovations but part of a broader behavioral pattern tied to increasing ecological range.

The team emphasizes that this expansion doesn’t suggest a single evolutionary breakthrough. Rather, it marks a confluence of environmental pressures, population dynamics, and learned behavior. Africa, in this view, was less a Garden of Eden and more a crucible of experimentation.

Why This Matters

The dispersal out of Africa wasn’t an escape. It was the continuation of a process already well underway on the continent. By the time the ancestors of all non-African humans crossed into Eurasia, they had spent tens of thousands of years becoming generalists in Africa's forests, deserts, and everything in between.

"Our results suggest that the roots of human global success run deep in Africa," said Emily Hallett. *"Understanding that history means recognizing the continent not just as our origin point, but as the proving ground of our species' extraordinary adaptability."

Suggested Related Research:

Zeller, E., & Timmermann, A. (2024). The evolving three-dimensional landscape of human adaptation. Science Advances, 10, eadq3613. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aadq3613

Banks, W. E., d'Errico, F., Peterson, A. T., Kageyama, M., Sima, A., & Sanchez-Goñi, M.-F. (2008). Human ecological niches and ranges during the LGM in Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(2), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2007.06.011

Timmermann, A., Friedrich, T., & Zeller, E. (2022). Climate effects on archaic human habitats and species successions. Nature, 604, 495–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04536-4

Raia, P., Melchionna, M., Mondanaro, A., & Carotenuto, F. (2020). Past extinctions of Homo species coincided with increased vulnerability to climatic change. One Earth, 3(4), 480–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.09.007

Roberts, P., & Stewart, B. A. (2018). Defining the 'generalist specialist' niche for Pleistocene Homo sapiens. Nature Human Behaviour, 2, 542–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0394-4

Hallett, E. Y., Leonardi, M., Cerasoni, J. N., Will, M., Beyer, R., Krapp, M., Kandel, A. W., Manica, A., & Scerri, E. M. L. (2025). Major expansion in the human niche preceded out of Africa dispersal. Nature, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09154-0