The Long Road South

When early humans crossed into the Americas over 15,000 years ago, they weren’t alone. Tagging along were the ancestors of Canis familiaris — the domesticated dog. But these companions didn’t arrive in South America all at once. According to new research published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B1, their journey southward came much later and was closely tied to the rise of farming.

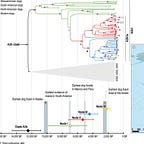

Researchers led by Dr. Aurélie Manin of the University of Oxford sequenced 70 complete mitochondrial genomes from ancient and modern dogs found across Central Mexico to Patagonia. Their findings paint a picture of migration not marked by rapid conquest, but by slow integration into new landscapes as maize agriculture took root.

"This study reinforces the important role of early agrarian societies in the spread of dogs worldwide," said Manin.

A Tale Written in DNA

By comparing genetic lineages, the team found that all pre-contact dogs in Central and South America descended from a single maternal clade, A2b1. This lineage diverged from its North American cousins between 7,000 and 5,000 years ago — precisely when maize farming began spreading through the Americas. This correlation suggests that dogs didn’t reach Central and South America until long after humans had already settled there.

The dispersal of dogs appears to follow a pattern known as "isolation by distance." Instead of rapid leaps, dogs moved gradually with farming populations, forming genetically distinct groups as they spread. Analyses showed clear genetic structure across regions, with mitochondrial lineages aligning with geographic divisions from the Andes to the Argentine pampas.

"Our results indicate a greater genetic similarity among dogs within the same region than between different regions," the authors noted, citing a strong north-to-south gradient.

Agriculture as Enabler

Why the delay? One answer lies in the lifestyle of early humans. Hunter-gatherers may have had little use for dogs in tropical environments full of hazards, disease, and predators. But as societies settled and began cultivating maize, dogs likely found a niche as scavengers, protectors, and perhaps companions.

The spread of agriculture created surpluses that made human settlements attractive. Dogs, in turn, adapted to the new diets and roles. Their dispersal echoes patterns seen in early cattle and pig management, where animals followed food and humans rather than leading the way.

"The evidence supports a model where dogs entered South America during the establishment of agrarian lifeways, not before," the study explains.

Displacement and a Chihuahua's Echo

Colonial contact in the 16th century brought sweeping changes. European dog breeds arrived en masse, largely replacing indigenous lineages. Today, most American dogs descend from these Eurasian imports. Yet one tiny breed carries a genetic whisper from the past.

Modern Chihuahuas, though thoroughly modern in most ways, sometimes retain mitochondrial DNA that connects them directly to their Mesoamerican ancestors.

"The ancient American origin of this lineage, still preserved in the mitochondrial DNA of some Chihuahuas, can be more precisely traced to Mesoamerican dogs," the study notes.

This rare continuity offers a poignant link to pre-contact America. It underscores how genetics can preserve traces of cultural heritage long after physical forms have changed.

Dogs as Cultural Companions

Dogs were more than just biological tagalongs. They played social, ritual, and economic roles in ancient American societies. From burial sites to diet analyses, dogs appear in contexts that suggest deep emotional and symbolic importance.

In many regions, dog remains are found in close proximity to human graves, sometimes buried with care. Such finds imply that dogs were not just animals but members of the community.

As the team notes, the study highlights "the importance of agrarian societies in the spread of dogs." It also points to broader patterns of animal-human relationships across continents and cultures.

The Path Ahead

This research opens new doors. The team emphasizes the need for nuclear DNA studies to complement the mitochondrial data. Nuclear genomes can reveal male-line ancestry and help untangle complex patterns of gene flow, hybridization, and population replacement.

Future work could also explore how dogs navigated environmental challenges—from parasites to predators—as they moved through diverse ecosystems.

"Isotopic analysis and ancient DNA from earlier periods will refine our understanding of the timing and nature of dog-human partnerships in the Americas," the authors conclude.

For now, a clearer picture emerges: dogs did not race into the Americas with the first humans. They followed, slowly and faithfully, down the winding path of agriculture, culture, and kinship—until one small Mexican breed echoed their journey.

Related Research:

Perri, A. R., Feuerborn, T. R., Frantz, L. A. F., Larson, G., Malhi, R. S., Meltzer, D. J., & Witt, K. E. (2021). Dog domestication and the dual dispersal of people and dogs into the Americas. PNAS, 118(6), e2010083118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010083118

Ní Leathlobhair, M., Perri, A. R., Irving-Pease, E. K., Frantz, L. A. F., et al. (2018). The evolutionary history of dogs in the Americas. Science, 361(6397), 81-85. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao4776

Bergström, A., Frantz, L., Schmidt, R., Ersmark, E., et al. (2020). Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs. Science, 370(6516), 557-564. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9572

da Silva Coelho, F. A., Gill, S., Tomlin, C. M., Heaton, T. H., & Lindqvist, C. (2021). An early dog from southeast Alaska supports a coastal route for the first dog migration into the Americas. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 288(1951), 20203103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.3103

Manin, A., Debruyne, R., Lin, A., Lebrasseur, O., Dimopoulos, E. A., González Venanzi, L., Charlton, S., Scarsbrook, L., Hogan, A., Linderholm, A., Boyko, A. R., Joncour, P., Berón, M., González, P., Castro, J. C., Cornero, S., Cantarutti, G., López Mendoza, P., Martínez, I., … Ollivier, M. (2025). Ancient dog mitogenomes support the dual dispersal of dogs and agriculture into South America. Proceedings. Biological Sciences, 292(2049). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2024.2443