When the hunter from Thung Binh Cave died some 12,000 years ago, the world around him was in transition. The glaciers of the Pleistocene were receding. Forests and rivers spread through what is now northern Vietnam. Life may have been changing, but it was still dangerous—sometimes because of other humans.

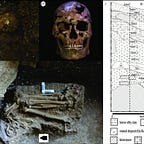

Excavated in 2018 from a limestone cave in the foothills of the Annamite Range, the skeleton—labeled TBH1—is one of the most complete human remains from Southeast Asia’s Terminal Pleistocene. At roughly 35 years of age, he had survived a harsh environment that claimed many long before middle age. Yet a closer look1 at his bones tells a more violent story.

A Rib Out of Place

One detail stood out immediately: TBH1 had an extra rib—a rare trait seen in less than 1% of modern populations. It might have gone unnoticed, except for the damage it carried. Near the man’s neck, the rib was fractured and bore the unmistakable signature of infection: a cloaca, an opening where pus drained from the bone.

Next to it lay a sliver of stone. Under the microscope, the flake revealed itself as a fragment of quartz, sharp-edged and triangular—likely from the tip of a projectile.

“The trauma and subsequent infection are the likely cause of death and, to our knowledge, the earliest indication of interpersonal conflict from mainland Southeast Asia,” wrote Christopher M. Stimpson and colleagues in their report.

The rib fracture had not killed him outright. Evidence of healing—a false joint, or pseudoarthrosis, formed where the pieces never fused—suggests he lingered for months. But the infection, untreated and unchecked, was almost certainly fatal.

The Arrow in the Cave

What the researchers cannot say is why this man was struck. Was it a raid? A personal quarrel? A skirmish over hunting grounds? There are no other skeletons in the cave to tell the rest of the story.

What is clear is that the weapon was primitive but lethal: a simple quartz flake hafted to a shaft, launched with a bow or spear-thrower. This discovery pushes back the earliest evidence of interpersonal violence in mainland Southeast Asia by thousands of years.

Violence and the End of the Ice Age

The Terminal Pleistocene was an era of profound ecological and cultural change. Sea levels were rising. Game distributions were shifting. Foraging bands across Southeast Asia were experimenting with new food strategies, domesticating dogs, and altering mobility patterns. Scarcity—or the perception of it—could have sharpened tensions between groups.

Well-preserved skeletons from this period are exceedingly rare. TBH1’s survival, and his death, now open a window into the social world of late Ice Age Southeast Asia. But a single case cannot answer whether violence was an anomaly or an undercurrent of daily life. More discoveries will tell.

For now, his bones speak of resilience and fragility: a man who endured injury, lived with pain, and ultimately succumbed not to the arrow itself, but to the infection it carried.

Related Research

Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. et al. (2021). Earliest evidence of interpersonal violence in the Pleistocene. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(9), 1187–1193. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01140-4

Larsen, C. S. (2014). Bioarchaeology: Interpreting Behavior from the Human Skeleton. Cambridge University Press.

Tung, T. A. (2012). Violence, Ritual, and the Wari Empire: A Social Bioarchaeology of Imperialism in the Andes. University Press of Florida.

Stimpson, C. M., Wilshaw, A., Utting, B., Mai Huong, N. T., Hao, N. T., Vu, D. L., Vimala, T., McColl, H., Breslin, E. M., Jones, E. R., Macleod, R., Holmes, R., O’Donnell, S., Kahlert, T., Khanh, S. P., Van Manh, B., Willerslev, E., & Rabett, R. J. (2025). TBH1: 12 000-year-old human skeleton and projectile point shed light on demographics and mortality in Terminal Pleistocene Southeast Asia. Proceedings. Biological Sciences, 292(2053). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2025.1819