A cave overlooking a vanished shoreline

On the Atlantic edge of Casablanca, surrounded today by quarries and suburbs, there is a cave with an unassuming name: Grotte à Hominidés. For decades, archaeologists treated it as one more promising but frustratingly incomplete site from Africa’s deep past. Fossils from the right time period, roughly one million to 600,000 years ago, are notoriously rare.

Now that gap has narrowed.

In a paper published in Nature,1 Jean-Jacques Hublin and colleagues describe hominin fossils from this cave that are dated with unusual precision to about 773,000 years ago. The age places these individuals close to a pivotal evolutionary moment, when the lineage leading to Homo sapiens split from the ancestors of Neandertals and Denisovans.

These are not spectacular skeletons. They are jawbones, teeth, vertebrae, and a femur bearing tooth marks from a carnivore. Yet together they speak to a question that has long hovered over human evolution: what did our last shared ancestors actually look like, and where did they live?

How to date a human ancestor without guessing

A magnetic timestamp in the rocks

Dating early human fossils often feels like triangulation by educated guesswork. Layers are missing. Methods disagree. Error bars balloon.

Thomas Quarry I is different. The sediments filling Grotte à Hominidés captured a global event that geologists love because it is both sudden and unmistakable: a reversal of Earth’s magnetic field. Around 773,000 years ago, magnetic north and south flipped, marking the boundary between the Matuyama and Brunhes chrons.

As Serena Perini explains:

“Seeing the Matuyama–Brunhes transition recorded with such resolution in the ThI-GH deposits allows us to anchor the presence of these hominins within an exceptionally precise chronological framework for the African Pleistocene.”

The team analyzed 180 magnetostratigraphic samples, an extraordinary resolution for a site of this age. The hominin bones sit squarely within the reversal itself, locking them into time with a margin of only a few thousand years.

For paleoanthropology, that kind of certainty is gold.

The bones in the cave

Fragmentary, gnawed, and revealing

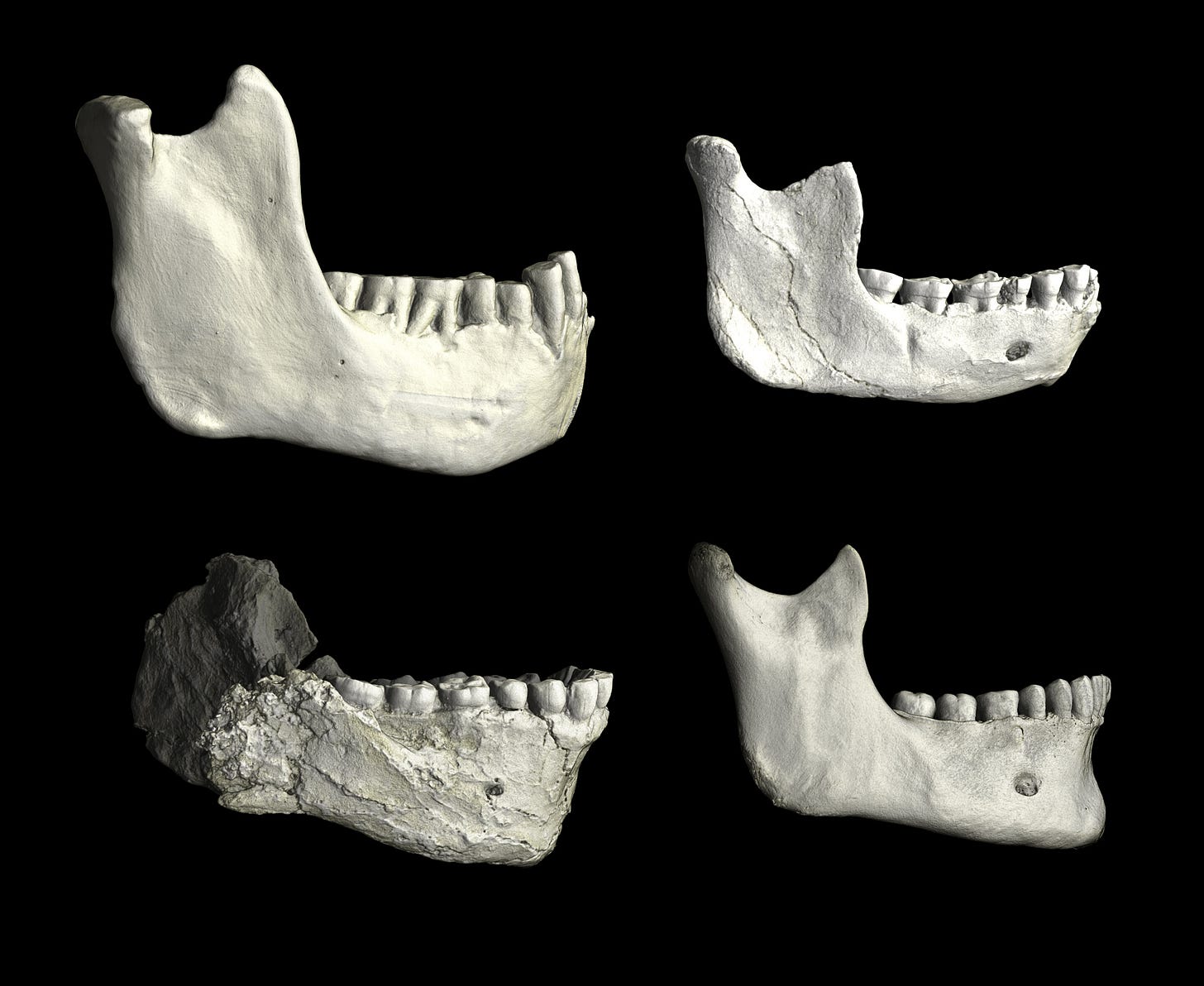

The fossils likely accumulated in what was once a carnivore den. A femur shows clear signs of chewing. The assemblage includes:

A nearly complete adult mandible

Half of another adult mandible

A child’s jaw

Isolated teeth and vertebrae

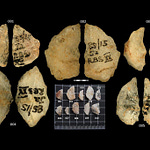

These remains were scanned with micro-CT and analyzed using geometric morphometrics. The goal was not to find a new species name, but to understand where these hominins fall on the family tree.

Matthew Skinner describes one key result:

“Analysis of this structure consistently shows the Grotte à Hominidés hominins to be distinct from both Homo erectus and Homo antecessor, identifying them as representative of populations that could be basal to Homo sapiens and archaic Eurasian lineages.”

In other words, they are not us. They are not Neandertals. They are something close to the point before that split.

Africa and Europe were not as separate as we imagine

Echoes of Homo antecessor

Some features of the Moroccan jaws resemble fossils from Gran Dolina in Spain, often attributed to Homo antecessor. That similarity hints at ancient population connections across the western Mediterranean.

But the resemblance only goes so far. Dental traits tell a different story. As Shara Bailey notes:

“In their shapes and non-metric traits, the teeth from Grotte à Hominidés retain many primitive features and lack the traits that are characteristic of Neandertals.”

By 773,000 years ago, these populations were already diverging. If exchanges occurred between North Africa and southern Europe, they likely happened earlier.

This fits with a broader picture of the Pleistocene Sahara as a shifting filter rather than a permanent wall. During wetter periods, grasslands and waterways linked regions we now think of as isolated.

A coastline rich in fossils and clues

Why Casablanca keeps delivering

The Moroccan Atlantic coast is a geological gift. Repeated sea level changes created dunes, caves, and cemented sands that preserve fossils with remarkable fidelity.

Jean-Paul Raynal described the setting this way:

“These geological formations, resulting from repeated sea-level oscillations, eolian phases, and rapid early cementation of coastal sands, offer ideal conditions for fossil and archaeological preservation.”

Thomas Quarry I is already famous for early Acheulean tools dated to about 1.3 million years ago. The new hominin finds deepen its importance, showing that this coast was occupied again and again by different human populations adapting to changing environments.

What these hominins mean for us

Closing in on the last common ancestor

Genetic evidence suggests that the split between the Homo sapiens lineage and the Neandertal Denisovan lineage occurred sometime between about 765,000 and 550,000 years ago. The Moroccan fossils sit right at the beginning of that window.

Jean-Jacques Hublin puts it plainly:

“The fossils from the Grotte à Hominidés may be the best candidates we currently have for African populations lying near the root of this shared ancestry.”

They are not a missing link in the old sense. Evolution rarely offers clean handoffs. But they bring us closer to seeing what that ancestral population might have been like, grounded firmly in Africa and already showing regional variation.

Nearly eight hundred thousand years after a predator dragged these bones into a coastal cave, they are helping us understand where our branch of the human story began.

Summary

The 773,000-year-old hominin fossils from Grotte à Hominidés in Morocco provide one of the most precisely dated windows into early human evolution. Their anatomy suggests populations close to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens, Neandertals, and Denisovans. The discovery reinforces Africa’s central role in our origins and narrows a long-standing gap in the fossil record.

Hublin, J.-J., Lefèvre, D., Perini, S., Muttoni, G., Skinner, M. M., Bailey, S. E., Freidline, S., Gunz, P., Rué, M., El Graoui, M., Geraads, D., Daujeard, C., Davies, T. W., Kupczik, K., Imbrasas, M. D., Ortiz, A., Falguères, C., Shao, Q., Bahain, J.-J., … Mohib, A. (2026). Early hominins from Morocco basal to the Homo sapiens lineage. Nature, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09914-y