A Color That Does Not Belong

The Gobi Desert is not known for glaze.

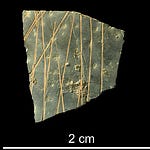

Its archaeology is usually muted in tone. Stone tools. Plain ceramics. Weathered bone. So when archaeologists walking the Delgerkhaan Uul hills of southeastern Mongolia noticed two small ceramic fragments1 shimmering blue green against the dust, they knew they were looking at something out of place.

Not just foreign, but far-traveled.

Those fragments, no bigger than a few fingers, have now become evidence for connections that stretched thousands of kilometers, linking mobile herders in the Gobi to workshops in the Persian world.

Finding the Sherds

Camps, Not Cities

The sherds were discovered in 2016 during the Dornod Mongol Survey, a long-running project designed to understand how mobile communities organized their lives across the Gobi over millennia.

They did not come from a palace or a city. They came from small seasonal herding camps.

One site, DMS 476, is marked mostly by medieval material associated with the Kitan-Liao and Mongol periods. Another, DMS 647, includes much older stone tools that point to Neolithic activity. Neither location suggests elite residence or imperial administration.

And yet, there they were.

As the authors note:

“The glazeware sherds were recovered from sites interpreted as small-scale, seasonal herding camps rather than permanent settlements or elite contexts.”

This context matters. It reframes who had access to imported goods, and how.

What the Glaze Revealed

Science Steps In

The fragments were too small to identify by shape or decoration. Instead, the team turned to chemistry.

Using scanning electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry, and portable X-ray fluorescence, the researchers analyzed the glaze itself. They then compared the results to hundreds of known samples from China and the Middle East.

The match was clear.

The glaze chemistry showed high sodium oxide and low aluminum and lime, a signature of soda-based alkaline fluxes made with relatively pure silica sand.

In other words, Persian glazeware.

The authors write:

“The chemical composition of the glazes is consistent with Early Islamic ceramics produced in the Persian world rather than with Chinese high-fired glazes.”

This rules out a Chinese origin, even though Chinese ceramics are well known from imperial centers like Karakorum.

Trade Beyond the Silk Road Stereotype

Not Just for Elites

Persian glazed ceramics are often interpreted as luxury goods, exchanged as tribute or diplomatic gifts among elites. That model works well in courts and capitals.

It fits less comfortably in a windswept herding camp.

The Gobi sherds suggest something else. They hint at trade networks that were flexible, intermittent, and embedded in nomadic life. Seasonal markets. Traveling merchants. Exchanges that did not require cities to function.

Ellery Frahm puts it this way:

“A far-traveled turquoise-colored glazeware sherd stands out due to its appearance, while a far-traveled but very plain sherd near it goes unnoticed.”

Color, in other words, shapes what survives archaeologically and what we notice.

Rare Object or Biased Record

Only two Persian sherds have been identified so far among thousands of ceramic fragments recovered by the survey. Are they genuinely rare, or are they simply easier to spot?

The authors are careful here. The Gobi is harsh. Freezing, thawing, erosion, and exposure can strip glaze from ceramics, leaving imported vessels indistinguishable from local wares.

Absence, in this case, is not strong evidence.

Nomads in a Connected World

The study joins a growing body of research showing that mobile pastoralists were not peripheral to long-distance exchange. They were participants.

Other exotic materials, such as carnelian beads, appear in similar contexts across Inner Asia. Their bright colors and distant origins signal status, identity, and connection.

The glazed sherds add another layer. They show that even objects associated with urban craft traditions could travel deep into landscapes shaped by mobility.

As Frahm notes:

“Now that we know about this phenomenon of Persian links, we can watch for less obvious indicators of these far-flung connections.”

The Gobi, it turns out, was not as isolated as it looks.

Summary

Two small blue-green ceramic sherds found in seasonal herding camps in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert have been identified as Persian glazeware using chemical analysis. Their presence challenges the idea that imported luxury goods circulated only among elites and cities, revealing flexible trade networks that reached mobile pastoralists during the Early Islamic period.

Frahm, E., Amartuvshin, C., Brennan, K., Chambers, A., Corolla, M., Cox, M., Deng, Z., Elzawy, H., Fiore, M., Graham, T. B., Herrmann, C., Honeychurch, W., Jiang, S., Kalinkos, L., Kronengold, H., Li, T. M., Mullan, J., Northrup, A., Ren, Y., … Zeng, L. (2026). Occurrences of Persian glazeware in the Gobi desert of Mongolia. Journal of Archaeological Science, Reports, 69(105545), 105545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105545