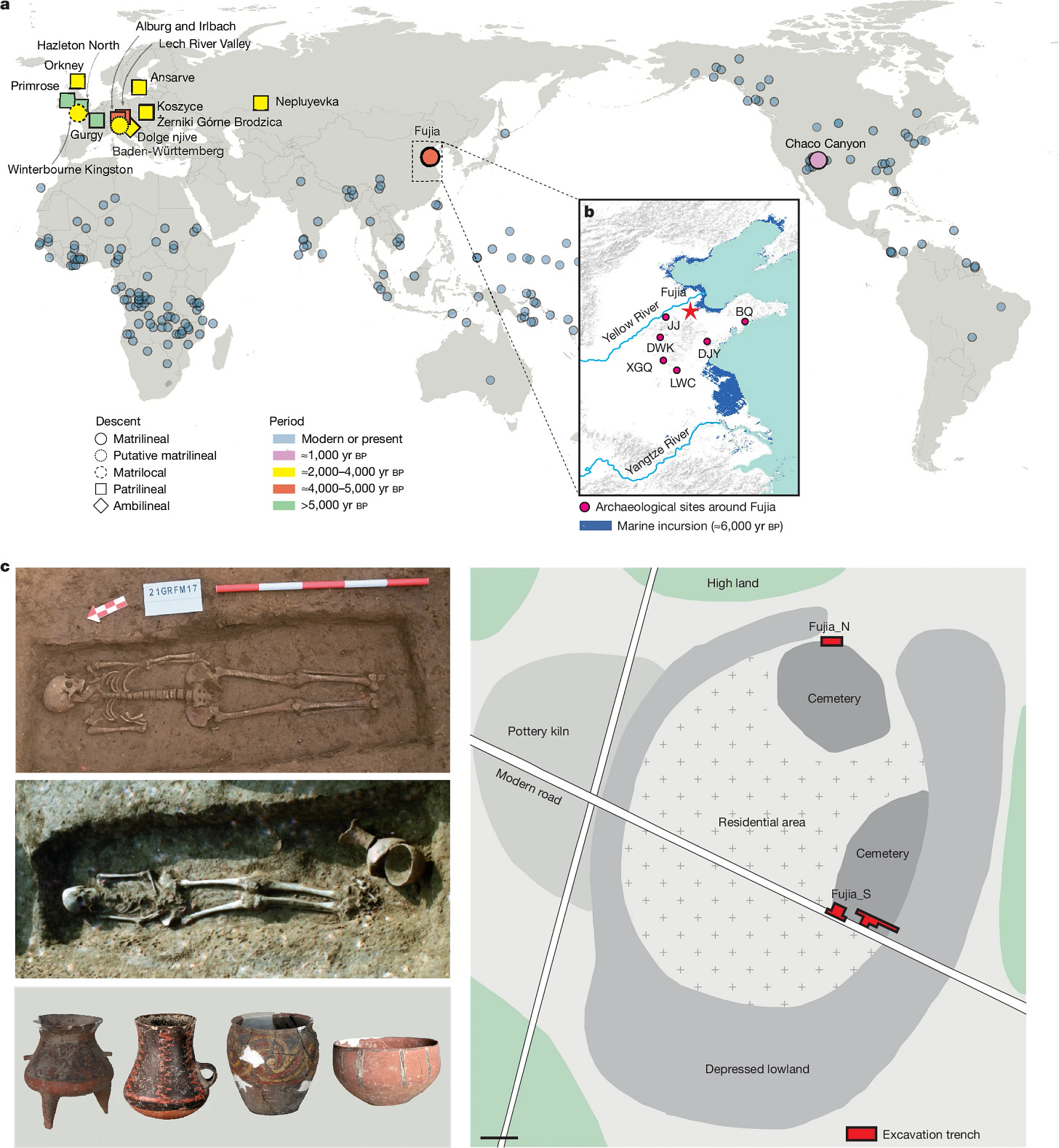

At the Fujia archaeological site in eastern China, 5000-year-old graves tell a story that might challenge deep-seated assumptions about how early human societies were organized. Nestled in the coastal lowlands of what is now Shandong Province, this Neolithic village appears to have operated under a social framework rarely seen in the ancient world: matriliny.

For more than 250 years, two distinct cemeteries at Fujia served as final resting places for members of two separate maternal lineages. Genetic analysis1 of ancient DNA extracted from the skeletal remains of 60 individuals reveals a striking pattern: people were buried not according to paternal ties or marital bonds, but based on maternal descent.

Cemeteries Divided by Mitochondria

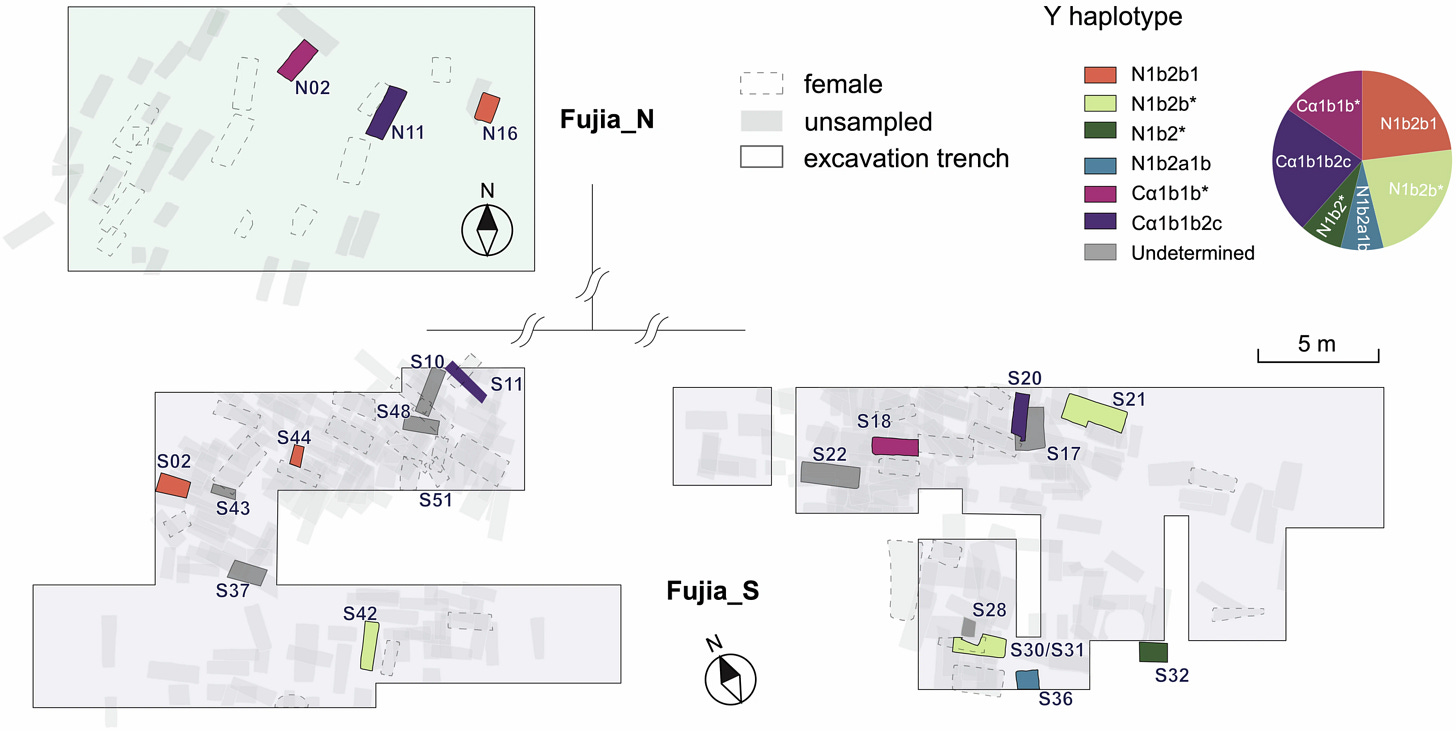

The Fujia site, part of the Dawenkou cultural complex (circa 2750–2500 BCE), comprises over 500 graves. Two cemeteries—Fujia_N and Fujia_S—sit on opposing ends of the site. Ancient DNA tells us these were not random divisions. Every individual sampled from Fujia_N belonged to mitochondrial haplogroup M8a3. Those from Fujia_S overwhelmingly carried a different haplogroup: D5b1b. These mitochondrial lineages, passed from mother to child, suggest a deep-seated and stable matrilineal structure.

"Individuals buried in the same cemetery not only shared the same mitochondrial haplogroup but often had identical sequences, pointing to close maternal kinship," the researchers wrote.

This pattern was consistent regardless of biological sex. Men and women were buried with their maternal clan, a stark contrast to the patrilocal patterns documented at many other Neolithic sites in China and Europe.

High Diversity in Y-Chromosomes, Low in Mitochondria

If the maternal lineages at Fujia were tight-knit, the paternal ones were remarkably diverse. Analysis of the Y chromosome in male remains revealed multiple unrelated paternal lines within each cemetery. This disparity suggests that while women stayed within their birth community, men likely came from outside. Yet despite these inflows, the maternal system remained intact.

"The burial practice based on maternal lineage remained strictly consistent," the authors noted, even when individuals from different cemeteries were related through avuncular or cousin ties.

Endogamy Without Inbreeding

The Fujia community also practiced high levels of endogamy—marriage within the same group. But notably, this did not result in widespread inbreeding. Analyses of runs of homozygosity (ROH) showed that while most individuals shared distant genetic links, close-kin marriages were rare.

This endogamy may reflect a practical response to demographic limits in a small, geographically constrained community. The villagers at Fujia rarely moved far, as suggested by isotope data that point to consistent childhood and adult residences within a 10-kilometer radius of the site.

Subsistence and Settlement

Stable isotope analysis confirms a millet-heavy diet, supplemented by domesticated pigs and possibly freshwater or marine resources. The site sits on what would have been fertile ground for foxtail millet and broomcorn millet cultivation. It may not have been a wealthy community—archaeological evidence points to modest grave goods and limited signs of elite stratification—but it was stable, organized, and cohesive.

Matriliny in a Broader Context

Matrilineal societies are rare today and often regarded as historical outliers. The few well-documented ancient cases include the elite lineages of Chaco Canyon in North America and scattered evidence from Iron Age Europe. Fujia now joins this short list with its dual-clan matrilineal model—a structured, inherited identity carried through mothers over ten generations.

"Fujia may represent a Neolithic version of clan-based matrilineal society, not dissimilar in structure to modern groups like the Mosuo or Tlingit," the researchers propose.

This discovery invites a reevaluation of prehistoric kinship systems. Rather than a linear evolution from matriliny to patriliny, human social organization may have followed more varied and context-dependent paths.

A Case for Persistence, Not Progression

The social model at Fujia did not collapse into patriliny or hierarchy despite increasing social complexity in other Dawenkou settlements. Fujia avoided the wealth disparities and elite tombs found in regional centers like Jiaojia. Instead, its people maintained a more egalitarian structure rooted in maternal ties.

In doing so, they remind us that human societies have long experimented with diverse strategies for organizing kinship, inheritance, and identity. The matrilineal clans of Neolithic Fujia were not a fleeting curiosity. They were an enduring way of life.

Related Research

Kennett, D. J., et al. (2017). Archaeogenomic evidence reveals prehistoric matrilineal dynasty. Nature Communications, 8, 14115. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14115

Gretzinger, J., et al. (2024). Evidence for dynastic succession among early Celtic elites in Central Europe. Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01888-7

Cassidy, L. M., et al. (2025). Continental influx and pervasive matrilocality in Iron Age Britain. Nature, 637, 1136–1142. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09238-w

Ji, T., Zhang, H., Pagel, M., & Mace, R. (2022). A phylogenetic analysis of dispersal norms, descent and subsistence in Sino-Tibetans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 43(2), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2021.11.006

Lu, Y., et al. (2012). Mitochondrial origin of the matrilocal Mosuo people in China. Mitochondrial DNA, 23(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.3109/19401736.2011.615899

Wang, J., Yan, S., Li, Z., Zan, J., Zhao, Y., Zhao, J., Chen, K., Wang, X., Ji, T., Zhang, C., Yang, T., Zhang, T., Qiao, R., Guo, M., Rao, Z., Zhang, J., Wang, G., Ran, Z., Duan, C., … Ning, C. (2025). Ancient DNA reveals a two-clanned matrilineal community in Neolithic China. Nature, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09103-x