Where Empires End and Daily Life Begins

In the grasslands of northeastern Mongolia, beyond where most medieval historians care to look, a heap of animal bones is quietly rewriting the story of one of Asia’s great empires. Excavated from a midden at “Site 23,” a Liao dynasty garrison post built a thousand years ago, the bones tell a tale the imperial record never did: what it took to stay alive on the empire’s edge.

The Liao dynasty (916–1125 CE), ruled by the semi-nomadic Khitans, spanned much of Inner Asia. Its elite left behind detailed histories filled with court intrigue, military campaigns, and seasonal hunts. But nearly nothing was said about the people stationed far from the capital, tasked with guarding the empire’s massive, rammed-earth wall that stretched across Mongolia and northern China.

This is what makes Site 23 so important. Excavated in 2022 by a team from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the National University of Mongolia, the garrison’s trash pit yielded over 7,000 animal bones—material rarely preserved in such volume on the open steppe.

“The historical texts tell us about emperors and hunts,” said zooarchaeologist Tikvah Steiner, who led the analysis. “But the bones show the actual labor of survival—animal husbandry, bone carving, decisions about butchery and breeding. This is frontier life, not imperial spectacle.”

A Wall Without a Voice

Stretching some 4,000 kilometers, the medieval wall system of northern China and Mongolia rivals the more famous Great Wall in scale. But unlike its southern cousin, this “northern line” wasn’t designed for tourists or chroniclers. It was built and staffed in obscurity, likely by a mix of Liao subjects and coerced locals, to monitor mobility—not to create a hard border.

The Liao sources—compiled long after the fact by Chinese scholars—hardly mention this northern wall. And until recently, archaeologists hadn’t either. Site 23, located in Dornod Province, Mongolia, changes that.

“This isn’t just a wall,” said archaeologist Gideon Shelach-Lavi. “It’s a logistical system. And at its nodes—like Site 23—real people lived, worked, and died.”

The Midden Speaks

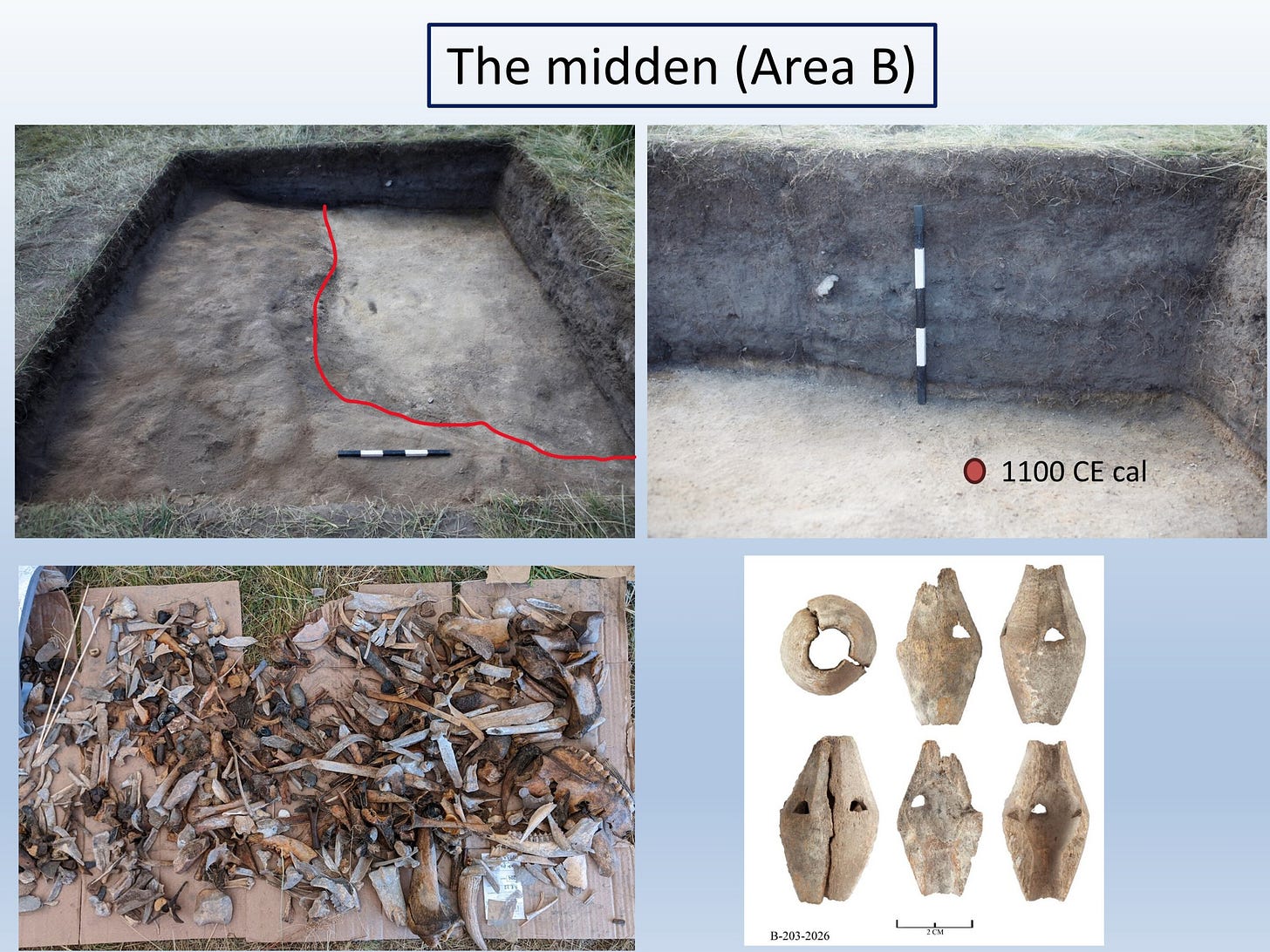

At the heart of the site lies a trash pit. Measuring 3 meters by 3 meters and a meter deep, it was packed with ash, burnt bone, worked tools, and ceramic fragments—evidence of years, perhaps decades, of continuous occupation. Radiocarbon dating places the midden at around 1050 CE, just as the Liao state was reaching its western limits—and its administrative strain.

From this midden emerged a detailed zooarchaeological profile:

Domestic sheep and goats made up the bulk of the diet.

Horses were numerous and spanned a full age range—suggesting on-site breeding.

Cattle were rare, possibly brought in only as draft animals.

Dogs, including many puppies, hint at guard roles—and hardship.

Gazelles, badgers, and catfish round out the picture, showing supplemental hunting and fishing.

“You can see decisions here,” said Rivka Rabinovich, co-author of the study. “What to raise, what to eat, what to burn. It’s a choreography of survival on a remote frontier.”

Harsh Winters and Lost Calves

One of the most striking patterns in the bone data was the unusually high number of neonatal deaths among lambs, kids, and puppies—many under six months old.

These weren’t routine culls. They suggest a late spring freeze or climatic disaster that wiped out vulnerable young animals. Such events, known in Mongolia as dzud, are still feared today.

“Ethnographic parallels with modern herders make this chillingly familiar,” Steiner observed. “A single bad storm in May can collapse an entire year's planning.”

This possibility aligns with historical records that mention escalating environmental crises in the final decades of the Liao Empire.

The Bureaucracy Forgot Them. The Bones Didn’t.

Historical texts like the Liaoshi emphasized elite pastimes—falconry, fur tribute, horse races. But they ignored the provisioning strategies of the very garrisons that enabled the empire’s expansion. At Site 23, we see people raising animals, burning bones for fuel, splitting cattle phalanges to extract marrow.

Even horses—the status symbol of the steppe—were not spared. Though rarely consumed in elite circles, Site 23’s midden includes horse bones with clear butchery marks. Survival, not symbolism, governed decisions here.

“This is where archaeology gives us a fuller picture,” said co-author Johannes Lotze. “Not just what the state thought was worth remembering—but how people lived.”

Borderlands in Context

While the Liao court had five capitals and claimed dominion over sedentary Chinese farmers and mobile steppe herders alike, its borders were porous, negotiated, and often tense. Tribes along the northern frontier were allies one year, raiders the next. Garrison life at sites like Site 23 was both a military function and a cultural negotiation.

Site 23 is not the only place in Inner Asia where this kind of local survival story emerges from imperial silence. Comparable data from:

Avraga, a Mongol-era settlement, reveals caprine herding and milk production through isotopic analysis.

Karakorum, capital of the Mongol Empire, shows a diverse urban economy—but one embedded in a broader steppe ecology.

Together, these sites help build a composite image of frontier life across centuries.

A People No Longer Silent

Thanks to the Site 23 midden, the forgotten garrison workers—be they Khitan soldiers, local tribesmen, or a blend of both—have left behind something more lasting than tribute lists or imperial decrees.

They left evidence of survival: burned hooves, marrow-split bones, whistling arrows carved from bone, and lamb remains curled mid-formation. They managed flocks, buried puppies, and fished catfish from rivers still icy in spring.

This is the archaeology of anonymity. And yet, it is the most human.

Related Research and Comparative Studies

Fijn, N. (2011). Living with Herds: Human–Animal Coexistence in Mongolia. Cambridge University Press.

Fenner, J. N., et al. (2020). Stable isotope and radiocarbon analyses of livestock from the Mongol Empire site of Avraga. Archaeological Research in Asia, 22, 100181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2020.100181

von den Driesch, A., et al. (2010). Animal economy in the ancient Mongolian town of Karakorum. Mongolian-German Karakorum Expedition.

Lefebvre, A. (2022). The Liao Empire and the Steppe: Horses, Warfare, and Frontier Politics. (Forthcoming).

Steiner, T., et al. (2025). Subsistence and survival along the medieval long-wall system of northern China and Mongolia. Archaeological Research in Asia, 43, 100639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2025.100639