Tattooed in Time: An Intimate Record from the Frozen Steppes

In the wind-scoured highlands of the Altai Mountains, where permafrost can seal secrets for millennia, a woman was buried beneath a log-lined tomb more than 2,000 years ago. Her skin, tattooed with a procession of ungulates, feline predators, and symbolic patterns, endured the centuries not by accident, but by ice. These preserved tattoos, part of the Pazyryk culture's Iron Age mortuary legacy, have long fascinated archaeologists and artists alike. But until now, the discussion has remained largely aesthetic—relying on monochrome drawings and interpretive guesses.

A new study in Antiquity1 changes that. By applying high-resolution near-infrared imaging and 3D modeling, a team of researchers led by Gino Caspari has gone deeper—not only into the pigments and patterns of ancient tattoos, but into the lives and hands of the people who made them. The study, published in Antiquity, captures an emerging anthropology of tattooing that places technical skill, apprenticeship, and individual creativity at its center.

"Tattooing emerges not merely as symbolic decoration but as a specialized craft—one that demanded technical skill, aesthetic sensitivity, and formal training or apprenticeship," the authors write.

A Canvas of Contrasts

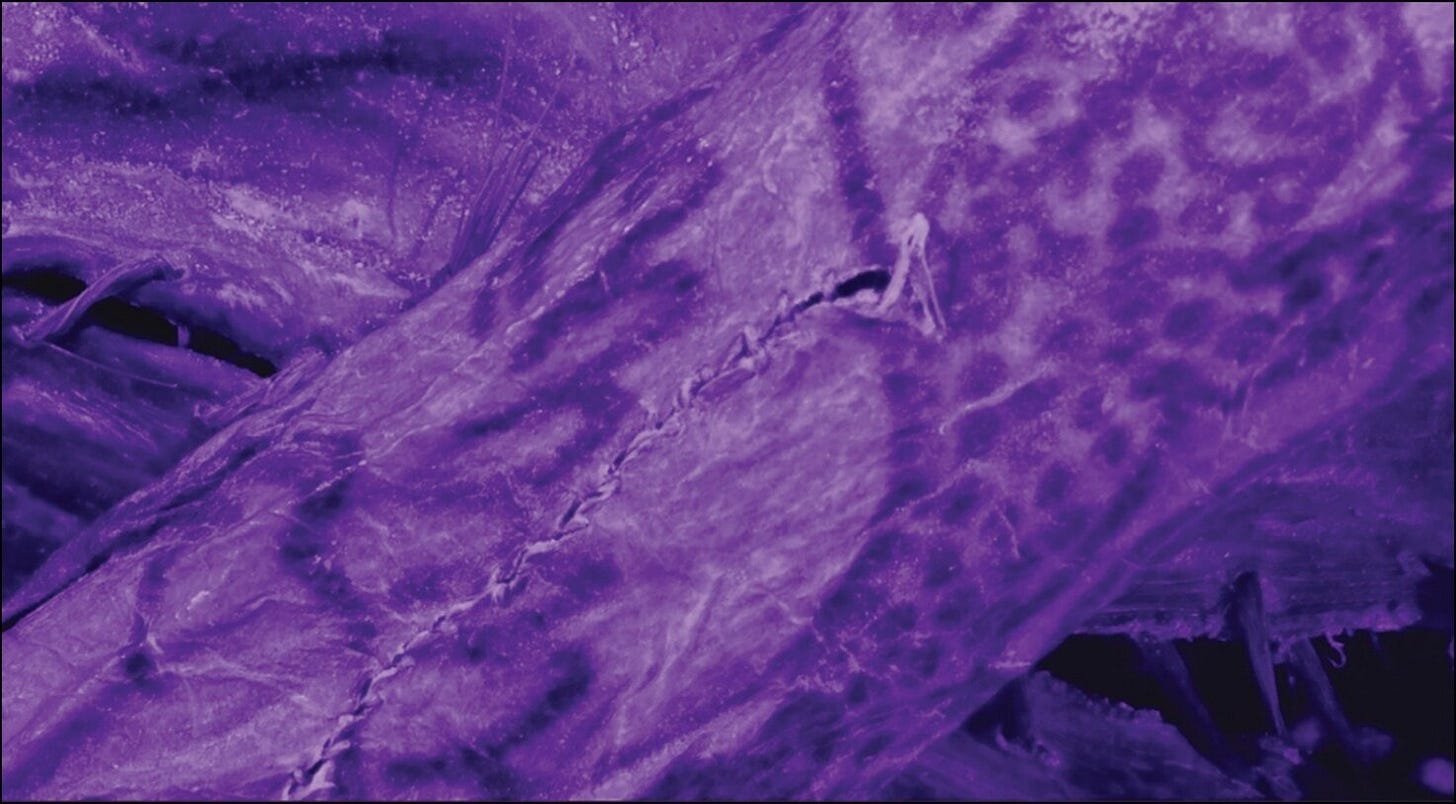

The subject of this analysis is the female mummy from Pazyryk tomb 5. Her forearms and hands bear detailed figural tattoos—some of the most sophisticated known from the ancient world. Thanks to sub-millimeter near-infrared scanning, previously invisible details surfaced. These revealed not only the designs, but clues about how they were made: the width and consistency of lines, the arrangement of motifs, the layering of ink—all suggest different tools and levels of technical refinement.

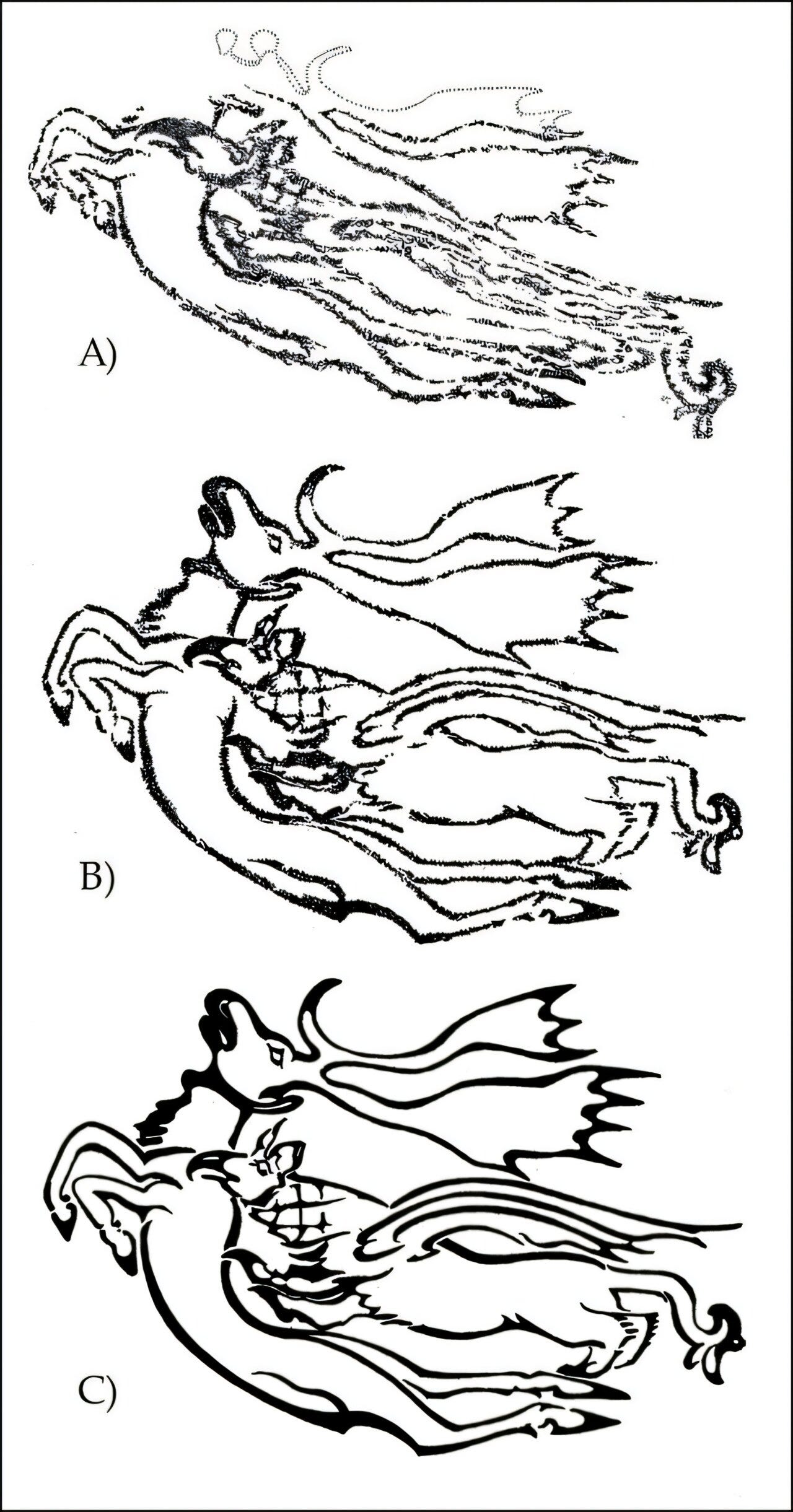

The left and right forearms, though decorated in similar themes, show striking asymmetry in execution. The right arm displays layered planning and complex compositions—a feline with forward-facing eyes, ungulates aligned to body contours, and motifs precisely placed for visual impact. The left arm’s design, by contrast, appears more rigid and less responsive to the body's form. Lines are thicker, the perspective is flatter, and anatomical details are simplified.

This divergence led researchers to a provocative conclusion: the tattoos were likely the work of two different artists, or possibly the same artist at different stages of skill development. Either way, it suggests a culture where tattooing was learned, practiced, and refined.

"The qualitative differences between these two compositions show the importance of gathering high-resolution data for the study of archaeological tattoos," Caspari notes.

Seeing the Artist in the Ink

The forearm is not just a location for display—it is a moving, living surface. The right-arm tattooist seems to have anticipated this, positioning a deer so its antlers curve with the wrist’s flex and aligning feline faces to gaze out toward the viewer. Such compositional awareness echoes choices made by modern tattoo artists working with the body’s motion and musculature. But this is Siberia, circa the 5th century BCE.

What emerges is a layered image of ancient practice: not casual marking, not mere symbolism, but a cultural tradition involving careful execution, sequential sessions, and likely, social apprenticeship. Motifs were not added randomly. They were placed with forethought, sometimes phased in over time, possibly under the guidance of more experienced artists.

"The right forearm likely required at least two sessions to complete," the researchers note, "beginning with the ungulate positioned at the wrist. This clever placement uses the contours of the wrist to enhance the form."

Technologies of Touch: What the Tools Reveal

No multi-point tattooing tools have yet been recovered from Pazyryk tombs, but the tattoos themselves tell a different story. The evenness of thick lines suggests the use of cluster-point tools rather than single-needle devices. Fine details—such as antler tips or facial features—required narrower, single-point instruments. Overlapping line ends and pigment buildup hint at pauses in work or changes in tools.

The researchers compared these ancient tattoos with experimental data from modern hand-poked tattoos made using reconstructed pre-electric tools. By tattooing identical patterns with different techniques, they established a library of physical signatures that helped reverse-engineer the Iron Age marks.

While other tattooing methods such as incision or subdermal stitching were considered, the Pazyryk evidence points consistently toward puncture techniques—specifically hand poking with soot-based pigments.

Not for the Dead: Tattoos as Life-World Markers

Interestingly, the tattoo designs were cut through during burial preparation. Deep sutures slice across the artwork, indicating that the tattoos were not protected or preserved as sacred images during mortuary rites.

This suggests that their social or symbolic significance may have ended with death. Unlike tattooing traditions in which body marks guide the spirit into the afterlife, Pazyryk tattoos appear deeply tied to life itself—perhaps reflecting status, identity, or personal experience rather than ritual preparation for death.

"The apparent disregard for preserving tattoo designs during Pazyryk burial preparation suggests that the social or spiritual function of the marks ended with the death of the individual," the study observes.

Craft Specialization on the Steppe

The diversity of designs across different individuals—seven tattooed mummies are known from the Altai—indicates that tattooing was not rare, nor restricted to elites. The craftsmanship required, however, suggests that tattooers occupied distinct roles, likely with specialized training. Just as blacksmiths or weavers developed skills passed down through generations, so too might tattooists have cultivated aesthetic techniques and tool use through apprenticeship.

Caspari and colleagues argue that the study of ancient tattoos offers a rare opportunity in steppe archaeology to center the prehistoric individual as an agent of creativity, rather than as a passive cultural carrier.

"Without the information offered by near-infrared photography, subtle details such as overlaps at the end of lines where the tattooist needed to adjust position or reapply pigment would be invisible," the researchers write.

This shift—toward identifying hands behind the marks—is part of a broader movement in archaeology to recover not just the what, but the who.

Related Studies and Resources

Here are additional studies that enrich our understanding of prehistoric tattooing and body modification:

Deter-Wolf, A., Robitaille, B., Krutak, L., & Galliot, S. (2016). The world's oldest tattoos. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 5, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.11.007

Robitaille, B., Deter-Wolf, A., & Jacobsen, M. S. (2024). Global diversity and distributions of traditional tattooing tools: An ethnographic, ethnohistorical, and anthropological perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Body Modification. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197572528.013.4

Caspari, G., et al. (2025). High-resolution near-infrared data reveal Pazyryk tattooing methods. Antiquity. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10150

Deter-Wolf, A., Riday, D., & Jacobsen, M. S. (2022). Examining the physical signatures of pre-electric tattooing tools and techniques. EXARC Journal. https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10654

Deter-Wolf, A., et al. (2024). Pre-Columbian tattooing methods on the Peruvian central coast. Andean Past, 14. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol14/iss1/16/

Caspari, G., Deter-Wolf, A., Riday, D., Vavulin, M., & Pankova, S. (2025). High-resolution near-infrared data reveal Pazyryk tattooing methods. Antiquity, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10150