Changing Bodies Across Deep Time

The Atacama Desert is often presented as a place where time holds still. Wind scours the same slopes that ancient hunter-gatherers once crossed, and some of the oldest artificially prepared mummies in the world lie beneath its dust. Yet, while the desert has barely changed, its people have. The skulls and skeletons preserved in this hyper-arid landscape now serve as unlikely witnesses to a biological story that stretches from early Holocene foragers to the citizens of modern Chile.

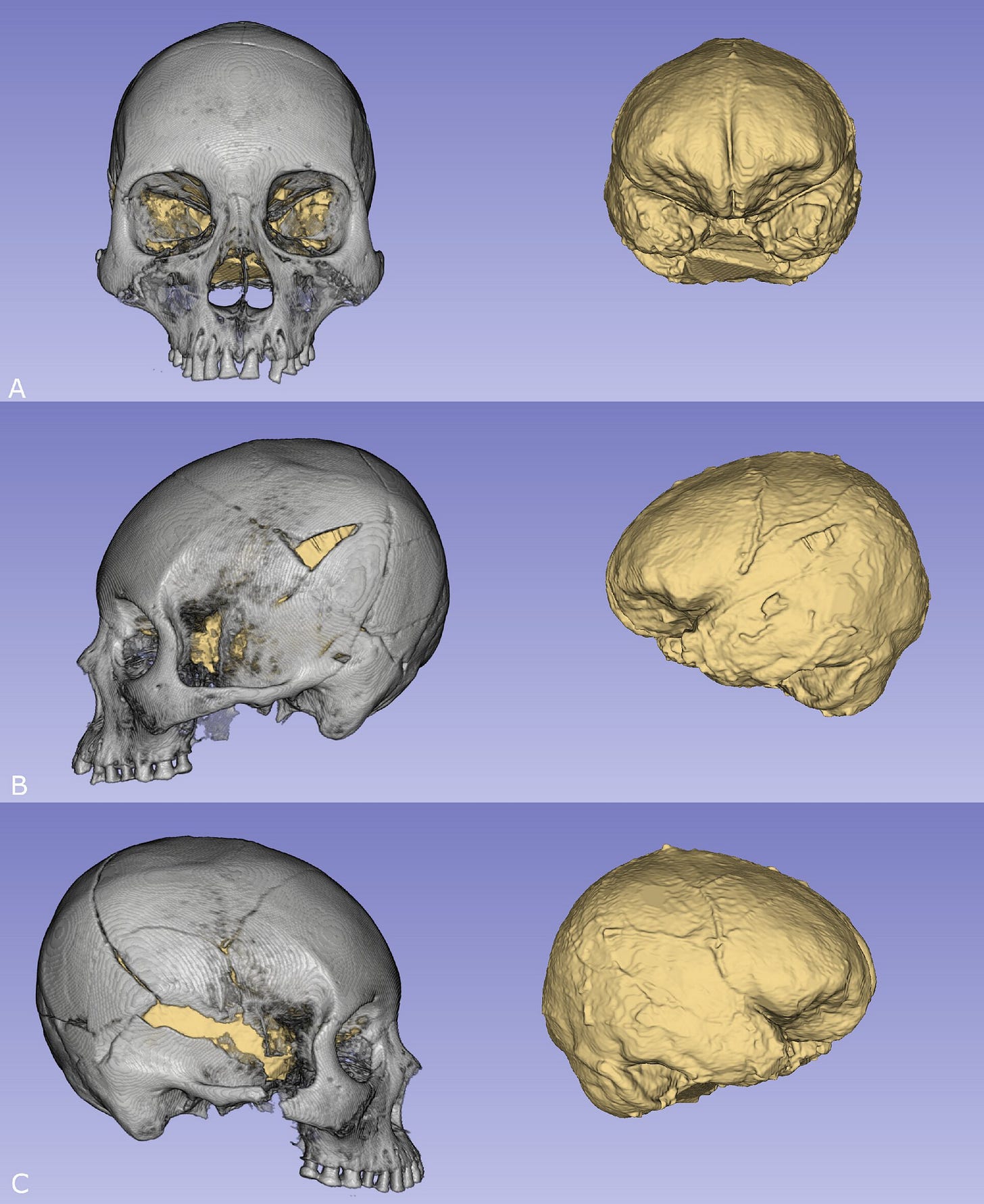

A new study in Scientific Reports1 analyzes intracranial volume, body size, and dietary signatures in Chinchorro mummies, early farming communities, and today’s Chileans. The researchers set out to address a deceptively simple question: how much have human bodies changed across millennia in northern Chile, and why?

The answer points not to the rise of agriculture, nor to major shifts in ancestry, but to the transformative power of the modern world.

“Morphological change on this scale reflects environmental force rather than evolutionary distance,” says Dr. Maritza Gálvez, a biological anthropologist at the Universidad de Chile. “Bodies respond to lived conditions long before genes have time to follow.”