A Continent Before Timeframes

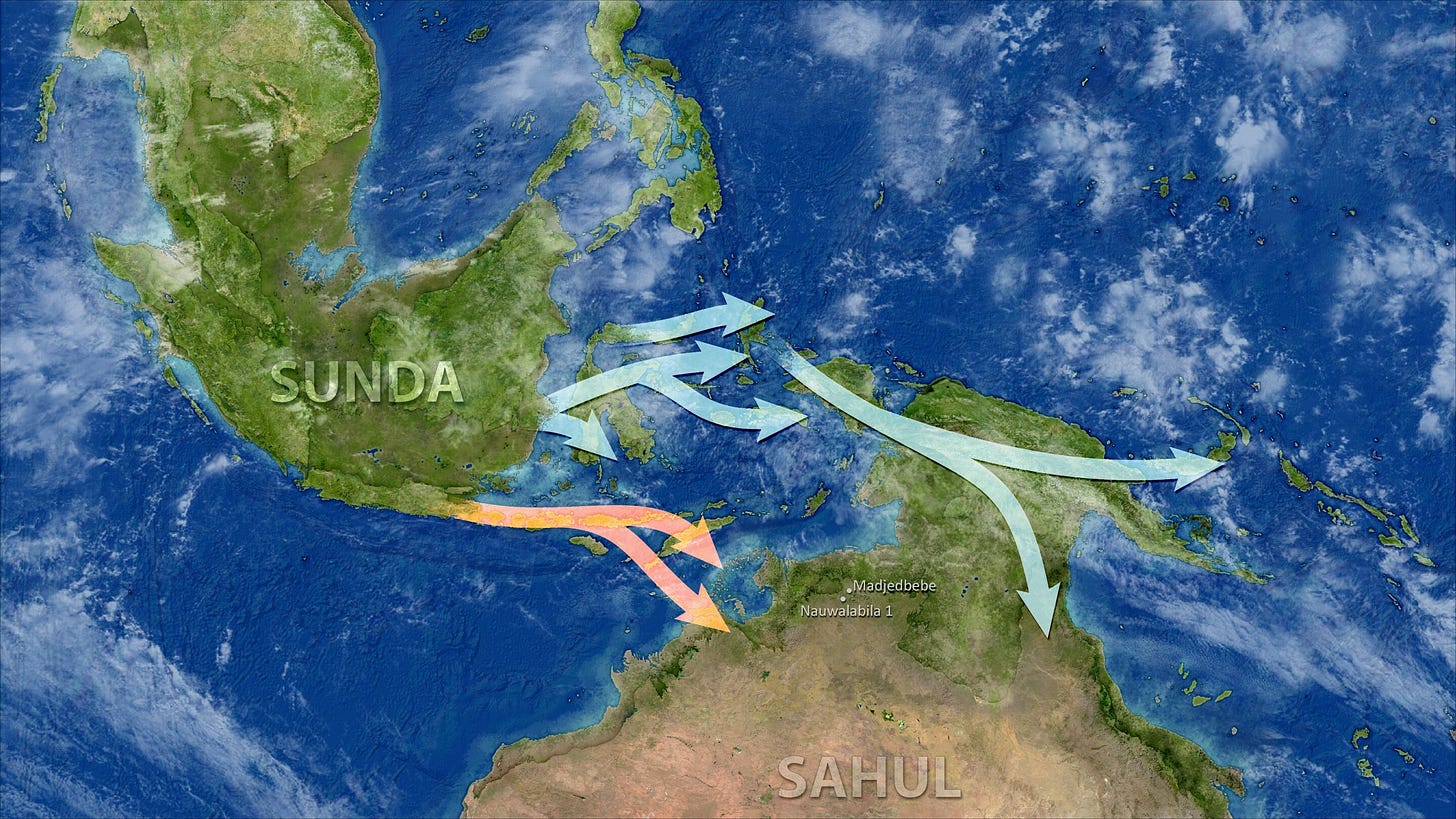

For decades, the opening chapter of human history in Sahul, the Ice Age supercontinent that once joined Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania, has been contested ground. Archaeologists, geneticists, and paleoanthropologists have traced its earliest footprints through scattered tools, fire pits, and bone fragments. Yet the timeline of when those first travelers stepped ashore has remained stubbornly fuzzy.

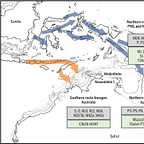

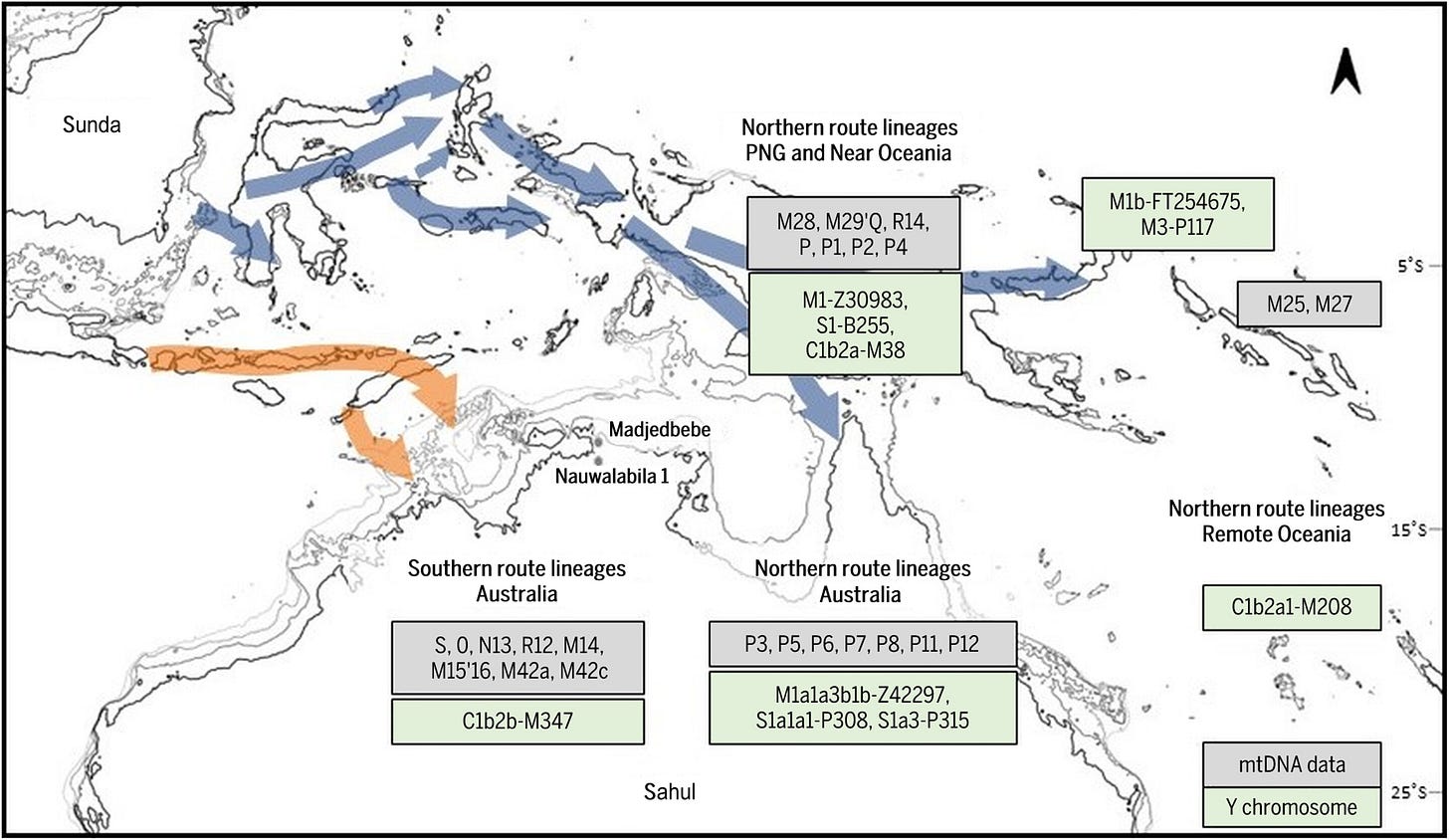

A new study in Science Advances1 now sharpens the picture with one of the most comprehensive Indigenous genomic datasets to date. Instead of a single, late pulse of migration, the authors present evidence for a much earlier arrival around 60,000 years ago, carried by not one but two genetically distinct groups navigating separate routes into Sahul.

This finding supports what scholars call the “long chronology,” a framework that pushes the earliest human presence in Sahul to the edge of the known Homo sapiens dispersal story. It also reframes how we think about the ingenuity and adaptability of the earliest peoples who ventured into the vast and rising Pacific.

“The genetic patterns indicate deep time depth and structured movements rather than a single wave washing uniformly across the landscape,” says Dr. Corinne Delacourt, an evolutionary geneticist at Université de Montréal.

“The story is one of branching paths, split decisions, and sustained population histories.”