Two Kinds of Ancestors on the Same Ancient Ground

The Afar Rift in Ethiopia has long served as a theater of human origins, and every so often it delivers a fossil that unsettles the script. One such find, unearthed in 2009 at Woranso-Mille, was an oddly built foot. Its big toe jutted outward like a grasping thumb, more reminiscent of Ardipithecus ramidus than of the famous Australopithecus afarensis specimens found elsewhere in the region. Yet the fossil dated to 3.4 million years ago, squarely within the reign of Lucy’s species.

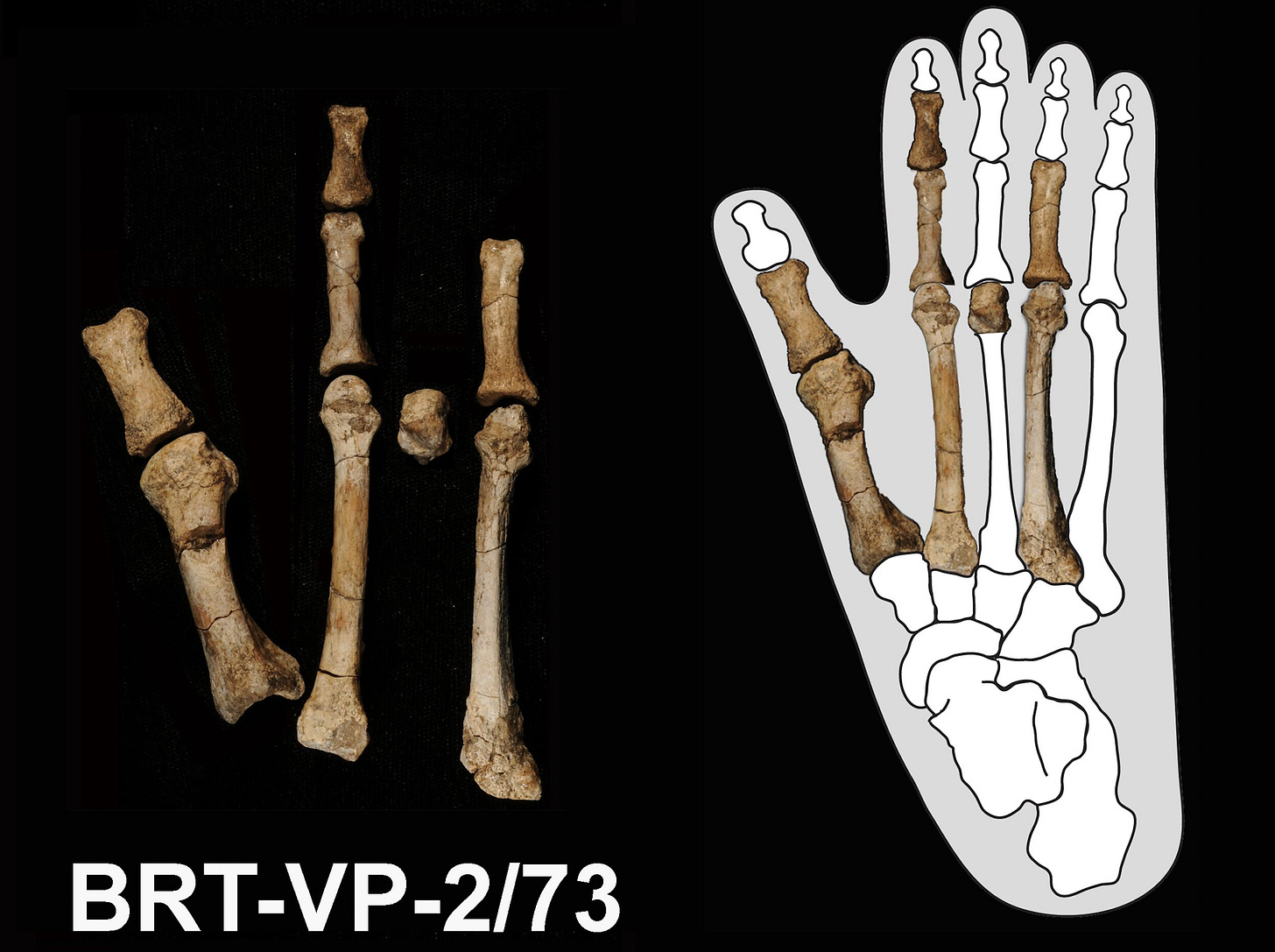

The foot, known as the Burtele specimen, was clearly hominin, clearly ancient, and clearly out of place.

Scientists hesitated to give it a name. Foot bones alone, without jaws or teeth, can mislead even seasoned paleoanthropologists. But after more than a decade of careful fieldwork, new fossils finally provide1 the anatomical connections required to place the foot where it belongs: in the species Australopithecus deyiremeda.

“The coexistence of two closely related hominins in the same landscape speaks to ecological partitioning on a scale rarely documented in early human evolution,” says Dr. Elena Rossi, a paleoanthropologist at Cambridge University.

The updated picture is not a minor correction. It changes the way researchers understand locomotion, diets, and childhood development among ancient hominins, and it shows that multiple evolutionary experiments were unfolding in parallel rather than in a single linear march toward Homo sapiens.