In the loamy floodplains of eastern Hungary, archaeologists have been peeling back layers of history at the site of Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom. There, a Bronze Age cemetery reveals not just how people died but how they lived, moved, and fed themselves over generations. A new study published in Scientific Reports1 leverages isotopic, botanical, and osteological data to reconstruct daily life in the region during a period of seismic cultural change.

Spanning the transition between the Middle and Late Bronze Age—roughly 2000 to 1300 BCE—the research team analyzed human remains from five burial sites in the Tisza River basin, focusing on carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and strontium (Sr) isotopes, along with botanical micro-remains trapped in ancient dental calculus. The result is a textured narrative of how subsistence, mobility, and social structure were transformed around 1500 BCE with the emergence of the so-called Tumulus Culture.

"The change of material culture, settlement patterns, and burial customs coincided with a substantial modification of other fundamental aspects of culture, namely subsistence practices, primary economy, dietary habits, and presumably, cuisine."

From Tells to Tumuli: Abandoning the Fortified Settlements

Bronze Age life in the Carpathian Basin was once organized around tell settlements—fortified, long-term habitation sites perched atop mounds of accumulated occupation debris. These centers reflected not just architectural investment but social hierarchy. Around 1500 BCE, however, these tells were abandoned. In their place emerged more horizontally organized settlements associated with the Tumulus Culture, named for its distinctive burial mounds.

This architectural shift mirrored a broader social reorganization. Evidence suggests that rigid hierarchies and unequal food distribution in Middle Bronze Age communities gave way to a more level playing field during the Late Bronze Age. Protein-rich diets that once signaled elite status became less differentiated across gender and age. Instead, cereal-based diets dominated.

What People Ate, and What That Says About Power

Stable isotope analysis of human bone collagen revealed a significant reduction in nitrogen isotope values (δ15N) in the Late Bronze Age compared to the preceding Middle Bronze Age. This shift implies a decline in animal protein consumption, challenging long-held assumptions about the pastoralist orientation of the Tumulus Culture.

"The wider variability of nitrogen isotope values during the Middle Bronze Age suggests greater food variety and more differentiated access to protein. Middle Bronze Age society was probably more stratified."

Carbon isotope values (δ13C), meanwhile, show a rise consistent with the introduction of C4 plants—specifically, broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum). Radiocarbon dating places this dietary pivot between 1540 and 1480 BCE, making it one of the earliest instances of millet agriculture in Europe.

The Millet Revolution

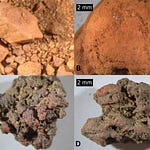

Dental calculus samples from Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom captured this transition at a microscopic level. Starch granules and phytoliths indicated the presence of wheat, barley, and crucially, broomcorn millet. While only two Middle Bronze Age individuals showed signs of millet consumption, nearly all Late Bronze Age individuals who consumed cereals showed evidence of millet.

"The strong investment in broomcorn millet as a key cereal began between 1540 and 1480 BCE, a strategy likely adopted for its high yield, short growing season, and drought resistance."

Mobility Without Mass Migration

Strontium isotope ratios from tooth enamel painted a picture of mostly local origins. The vast majority of individuals were born and raised within 20 kilometers of their burial site. However, a handful of outliers appeared—some from the Upper Tisza basin, others from as far as the Middle Danube or Southern Carpathians. Migration patterns shifted subtly between the two periods: Middle Bronze Age migrants tended to come from the north, while Late Bronze Age newcomers traced westward paths, aligning with the broader expansion of the Tumulus Culture.

"The Tisza basin, despite its geolithological uniformity, exhibits slight but significant isotopic discrepancies that enable the detection of sub-regional mobility."

Reconsidering Social Complexity in Prehistoric Europe

The evidence challenges conventional models that equate social complexity with inequality and mobility with conquest. Rather than abrupt population replacement, the shift toward the Tumulus Culture appears to have involved limited migration, accompanied by internal reorganization of diet, settlement, and status markers.

It is a reminder that cultural change in prehistory was not always dictated by elites, nor necessarily by outsiders. Instead, communities adjusted to environmental and demographic pressures in their own ways—sometimes by adopting new crops, redistributing protein, or even walking away from centuries-old settlements.

As stable isotope science continues to refine its temporal and geographic resolution, the bones of Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom are yielding something rare: a view of transformation that is quiet, granular, and local.

Related Research

Filipović, D., et al. (2020). "New AMS 14C dates track the arrival and spread of broomcorn millet cultivation and agricultural change in prehistoric Europe." Scientific Reports, 10, 13698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70495-z

Cavazzuti, C., et al. (2021). "Human mobility in a Bronze Age Vatya ‘urnfield’ and the life history of a high-status woman." PLOS ONE, 16(7), e0254360. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254360

Gamarra, B., et al. (2018). "5000 Years of dietary variations of prehistoric farmers in the Great Hungarian Plain." PLOS ONE, 13(6), e0197214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197214

Mārcis A. et al. (2022). "Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes identify nuanced dietary changes from the Bronze and Iron Ages on the Great Hungarian Plain." Scientific Reports, 12, 21138. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21138-y

Cavazzuti, C., Horváth, A., Gémes, A., Fülöp, K., Szeniczey, T., Tarbay, J. G., McCall, A., Rubio, B. G., Vicze, M., Bárány, A., Pető, Á., Magyari, E. K., Darabos, G., Futó, I., Lisztes-Szabó, Z., Molnár, E., Novak, M., Gál, E., Fischl, K. P., … Hajdu, T. (2025). Isotope and archaeobotanical analysis reveal radical changes in mobility, diet and inequalities around 1500 BCE at the core of Europe. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 17494. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01113-z