The Soil Remembers

On the floodplains east of Basra, thousands of low, linear ridges—barely visible unless viewed from the sky—stretch for kilometers in eerie geometric repetition. These ridges, nestled within the silty soil of the Shaṭṭ al-ʿArab, have long been believed to be the remnants of a medieval agricultural system powered by enslaved labor. Now, for the first time, archaeologists have pulled direct dates from this forgotten infrastructure. And those dates are changing the story.

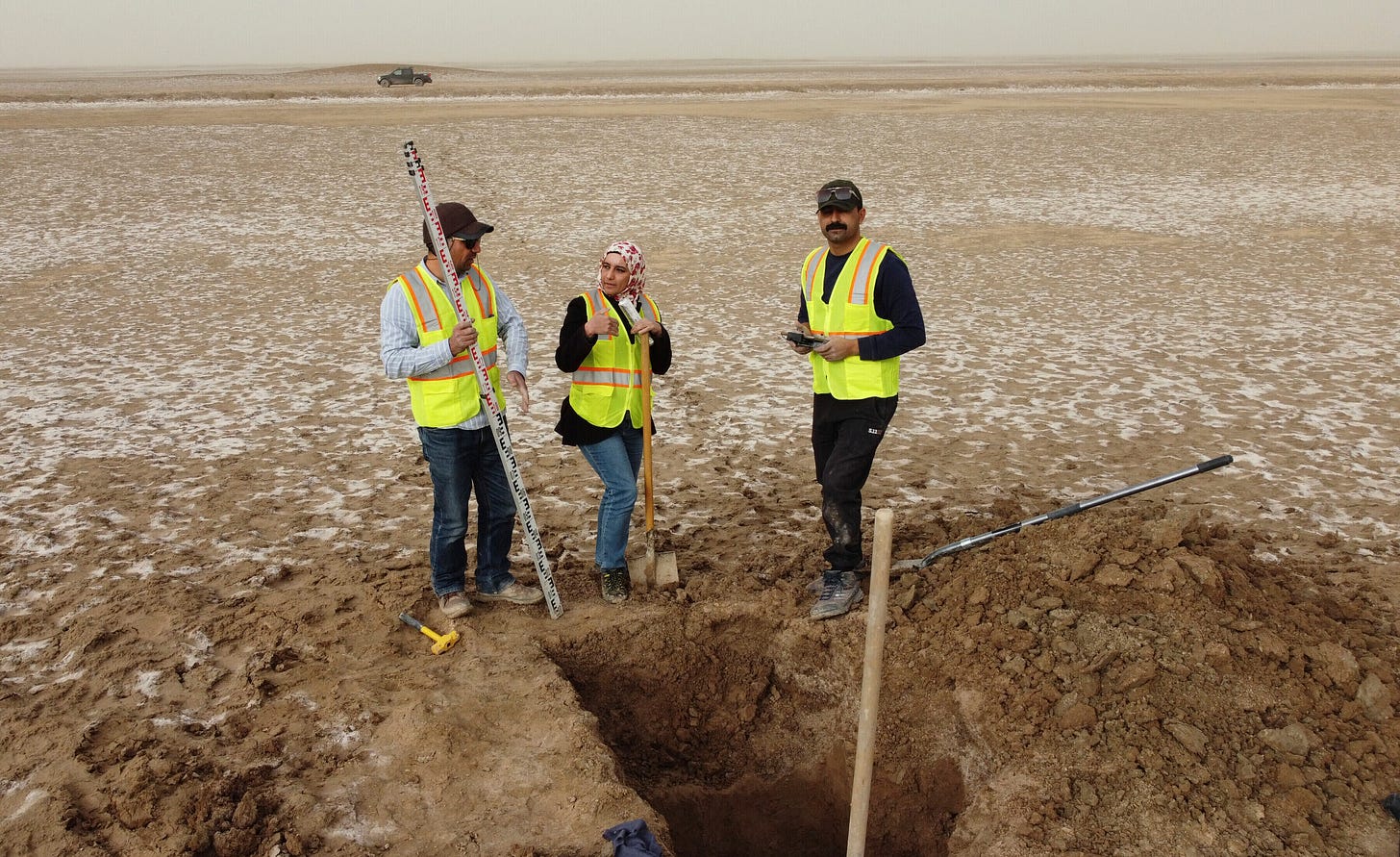

Published in Antiquity1, the study led by Peter J. Brown, Jaafar Jotheri, and an international team offers a new chronology of these massive ridge-and-canal features. The researchers used optically stimulated luminescence (OSL)—a technique that measures the last time minerals in the soil were exposed to sunlight—to directly date the sediments in these structures. Their findings show that the earthworks were built and used over a much longer period than previously thought—extending well into the 13th century CE, long after the famed Zanj Rebellion had been crushed by Abbasid forces.

“These features were not the ephemeral scars of a single insurrection,” the authors write, “but the enduring imprint of centuries of cultivation and control.”

The Ghosts of Labor

The Zanj Rebellion is one of the most dramatic episodes in the early Islamic world. In 869 CE, tens of thousands of enslaved people—many from East Africa, others possibly of local descent—rose up in southern Iraq. For nearly 15 years, they seized towns, built their own administrative center (al-Mukhtārah), and challenged the might of the Abbasid Caliphate.

The rebellion has often been linked to these earthworks. Medieval Arabic sources such as al-Ṭabarī describe the rebels as laborers consigned to agricultural zones where they were forced to dig canals and raise embankments in the salty, flood-prone terrain. The assumption—long repeated in historical literature—was that the ridges visible today were a product of this coerced labor, created in the decades leading up to the revolt.

But archaeology had never caught up to the story.

OSL dating now paints a more nuanced picture. The majority of the ridges tested post-date the Zanj Rebellion, with most being constructed between the late 9th and mid-13th centuries CE. In other words, these features were not just relics of rebellion, but evidence of long-term investment in tidal irrigation—an engineering tradition that persisted well after the revolt had been suppressed.

A Landscape of Empire

The agricultural system itself was enormous. Covering over 800 square kilometers, it featured more than 7,000 ridges—long, narrow embankments 20 to 50 meters wide, often spaced a few hundred meters apart. These were paired with a sophisticated network of canals that captured tidal flows from the Gulf to irrigate inland fields.

“If laid end to end,” the authors estimate, “these ridges would stretch for 3,000 kilometers—nearly the width of the continental United States.”

This massive labor investment suggests a highly organized workforce. Whether that workforce was composed of enslaved Zanj or recruited locals remains a matter of debate. But what is clear is that the system required continual maintenance. Silt carried by irrigation water had to be cleared, canals dredged, and soil salinity managed—all tasks likely assigned to agricultural laborers whose daily lives are absent from written records.

One explanation for the longevity of the system lies in tidal irrigation itself. Medieval geographers such as al-Muqaddasī and al-Idrīsī described the unique dynamics of the Shaṭṭ al-ʿArab, where freshwater tides surged upriver twice daily, allowing for the efficient watering of date palms and barley fields. Even today, traces of this hydraulic system are visible from satellite imagery and drone photography, winding like veins through the desert crust.

History Below the Horizon

Previous scholars treated the Zanj Rebellion as a rupture—a moment when an oppressive regime built its own downfall through the exploitation of slave labor. But the new data suggest a different story: continuity, resilience, and perhaps adaptation. Some ridges may have had pre-rebellion origins, while others were added centuries later. The system did not collapse in the wake of revolt but instead evolved.

“There was no sharp break,” says the research team, “but rather a slow fading of infrastructure, likely shaped by multiple forces: plague, climate change, shifting markets, and war.”

Indeed, the 14th-century spread of the Black Death, combined with increasing aridity and the decline of Baghdad’s central role in Gulf trade, likely accelerated the eventual abandonment of this once-thriving landscape. The date palm groves faded, and the canals silted in. By the time Portuguese traveler Pedro Teixeira passed through in the 1600s, he described only saline flats and ruined dikes.

Whose Heritage?

Perhaps most compelling is the call for recognition.

“This is minority heritage,” notes Jaafar Jotheri, co-author and professor at the University of Al-Qadisiyah. “It deserves not just excavation, but protection.”

The descendants of the Zanj still live in southern Iraq. Their stories remain marginalized, their contributions overlooked. The ridges—silent and windblown—are among the few physical traces of that history. As archaeology reclaims their timeline, perhaps it can also help reclaim their voice.

Related Research

Egberts, E., Jotheri, J., Di Michele, A., Baxter, A., & Rey, S. (2023). Dating ancient canal systems using radiocarbon dating and archaeological evidence at Tello/Girsu, southern Mesopotamia, Iraq. Radiocarbon, 65, 979–1002. https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2023.40

Abu-Lughod, J. (1987). The shape of the world system in the thirteenth century. Studies in Comparative International Development, 22(4), 3–25.

Campbell, G. (2016). East Africa in the early Indian Ocean world slave trade: The Zanj revolt reconsidered. In Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World (pp. 275–303). Palgrave Macmillan.

Borsch, S., & Sabraa, T. (2017). Refugees of the Black Death: quantifying rural migration for plague and other environmental disasters. Annales de Démographie Historique, 134(2), 63–93. https://doi.org/10.3917/adh.134.0063

Fields-Black, E. L. (2008). Deep Roots: Rice Farmers in West Africa and the African Diaspora. Indiana University Press.

Brown, P. J., Jotheri, J., Rayne, L., Abdalwahab, N. S., & Andrieux, E. (2025). The landscape of the Zanj Rebellion? Dating the remains of a large-scale agricultural system in southern Iraq. Antiquity, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.72