For decades, archaeologists parsing skeletal remains across the Maya lowlands have often reached for the language of sacrifice. Skulls and isolated bones found in graves were interpreted as evidence of ritual violence or divine offerings. But what if that narrative is incomplete?

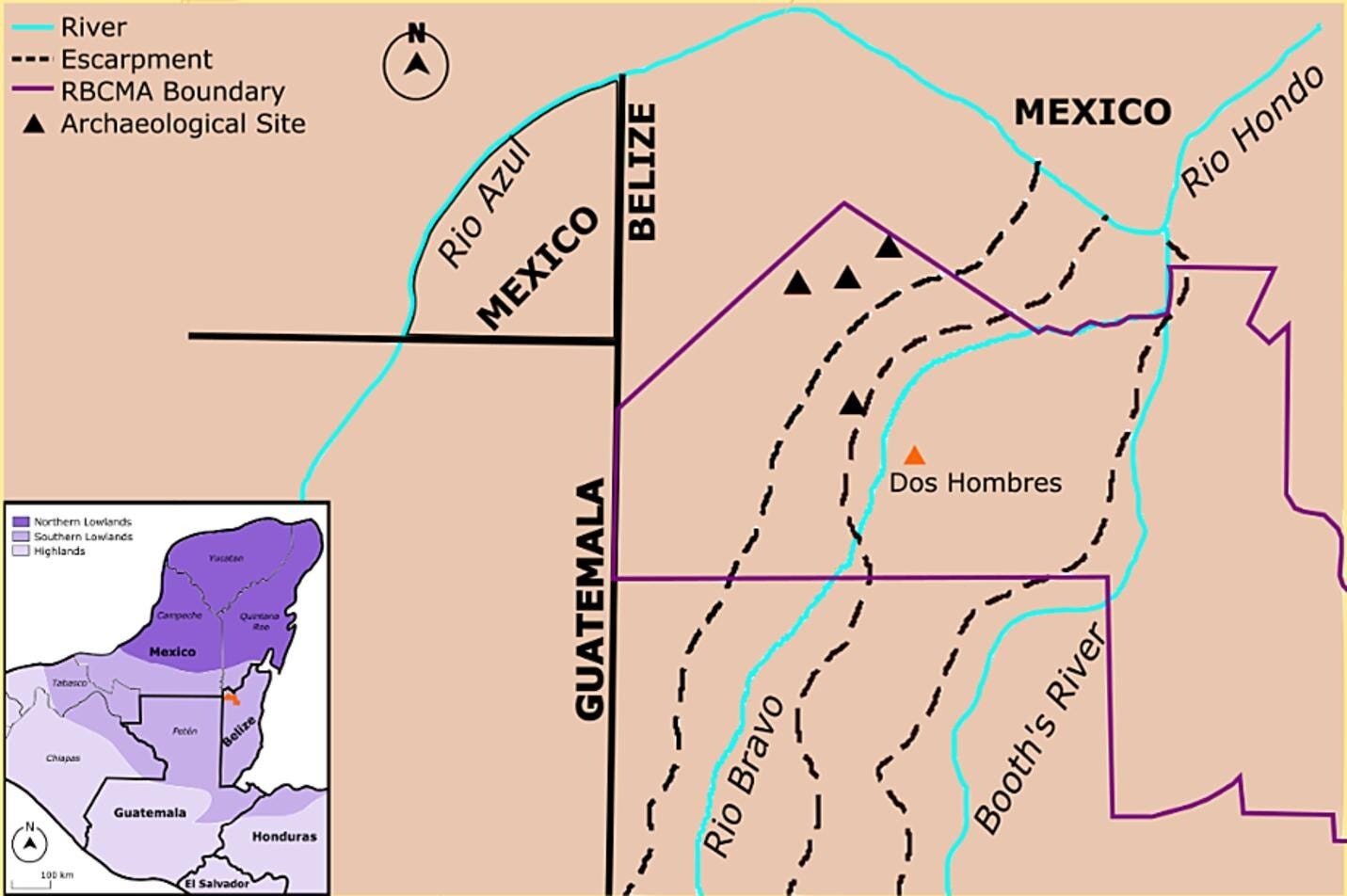

A study1 led by anthropologist Angelina J. Locker reexamines a modest burial outside the ancient Maya city of Dos Hombres, Belize. Her analysis brings a different lens: one rooted in memory, identity, and placemaking. Through isotopic analysis and a deep dive into Maya cosmology, Locker argues that disarticulated teeth and mandibles buried alongside a young woman were not sacrificial remnants, but ancestral fragments brought from afar to seed a sense of belonging.

Rethinking the Narrative of Sacrifice

The burial in question lies 1.5 kilometers outside the city center, in a commoner household known as the Dancer Group. Dated to the Late Preclassic (300 BCE – 250 CE), it contains the partial remains of a young woman (Individual 14), and two sets of disarticulated teeth from adults who were buried alongside her (Individuals 15 and 16).

Previously, these secondary remains had been cast as sacrificial victims. The prevailing wisdom: their bones, scattered and incomplete, suggested they were killed and interred to honor the primary burial. But no signs of violence were found on the bones. There were no cut marks, no indicators of flaying, no iconography of gods demanding blood.

"The use of sacrifice or interring one's enemies within the household of the everyday citizen seems unlikely," Locker writes.

Instead, she turns to Maya beliefs about the soul.

Teeth and Breath: Maya Ideas of the Self

Among the ancient Maya, identity was divisible. The body was more than bones and flesh—it was an assemblage of vital forces. The baah represented the self and resided in the head. Ik' was the breath-soul, linked to wind and embedded in the mouth and teeth. Ch'ulel dwelled in the blood and heart, while wahy were companion spirits who died when the individual did.

Because ik' was believed to reside in the teeth, the disarticulated remains may have been more than relics. They were portable repositories of ancestral breath.

"Disarticulated remains were used to strengthen the essence of ancestors to help create and legitimize place."

Isotopes and Identity: Tracing the Origins of the Dead

Locker analyzed oxygen and strontium isotope ratios from the teeth of the three individuals. These isotopes, locked in during childhood through water and food intake, reveal geographic origins.

Individual 14, the primary burial, was local. But Individuals 15 and 16 had isotope signatures that placed them outside the Dos Hombres region. They were migrants—or rather, their remains were.

"They most likely represent emergent ancestors of a dividual person from an external place."

These emergent ancestors may have been kin, real or fictive, whose remains were brought to the burial site to legitimize a new settlement, forge ancestral claims, and create continuity.

Memory in the Margins

The burial was marked by jade beads, a step carved in bedrock, and a U-shaped stone alignment—all elements often associated with grave markers or ancestor shrines. A deposit of freshwater mussel shells suggests a feasting event, reinforcing that this was a moment of community ritual.

This was not a grave of the forgotten. It was a grave meant to be remembered.

Later, during the Late Classic period, the area appears to have been reoccupied. Another burial, Episode 1, was inserted near the original one. One of the vessels from Episode 2 had been removed and reused. This act, Locker suggests, was more than reuse. It was a reengagement with memory. A reclaiming of lineage through material and spatial continuity.

Bones as Heirlooms

For the Maya, heirlooms were not just jade beads or ceramic vessels. Human remains could serve the same purpose.

Locker argues that the remains of Individuals 15 and 16 were not simply deposited. They were curated, brought from afar, and interred with intention.

"Bones of the dead can function as seeds for making place."

These dividual bodies carried memory, lineage, and power. Through them, the living constructed a genealogy of place.

This burial challenges assumptions baked into Mesoamerican archaeology. Not all partial burials speak to violence. Some speak to belonging.

Locker’s work encourages anthropologists and archaeologists to read bones not as evidence of what was done to people, but what was done with them.

When teeth are treated as sacred, when grave goods are sparse but symbolically dense, and when isotopes speak of distance, the story changes. A young woman buried at the edge of an ancient Maya city may have become the anchor of a new lineage—surrounded by ancestral breath, resting on bedrock, her grave remembered in stone.

Related Research

Geller, P. L. (2012). The bioarchaeology of socio-political change: A view from the ancient Maya. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2072-2

McAnany, P. A. (2013). Living with the Ancestors: Kinship and Kingship in Ancient Maya Society. Cambridge University Press.

Duncan, W. N., & Schwarz, K. A. (2014). Bodies and sacred matter: A bioarchaeological approach to religion in the past. University Press of Florida. https://doi.org/10.5744/florida/9780813049568.001.0001

Goudiaby, A., & Nondédéo, P. (2020). Death and identity: Reassessing the role of funerary practices in the construction of Classic Maya social organization. Ancient Mesoamerica, 31(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536119000321

Tiesler, V., & Cucina, A. (2007). Procedures in Human Heart Extraction and Ritual Meaning: A Taphonomic Assessment of Anthropogenic Marks in Classic Maya Skeletons. Latin American Antiquity, 18(4), 476–492. https://doi.org/10.2307/25478109

Locker, A. J. (2025). Dearly De-Parted: Ancestors, body partibility, and making place at Dos Hombres, Belize. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 78(101681), 101681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2025.101681