A New Way to Read the Ashes of an Ancient Industry

Archaeology often depends on what survives. For early metallurgy, that usually means the tools and ornaments that escaped decay, the occasional workshop floor, or the slag left behind by ancient fires. Yet these remnants are stubborn storytellers. They record chemical chaos, warped by heat and time, leaving researchers to infer entire technological systems from scraps that rarely speak with clarity.

At Tepe Hissar in northern Iran, a place associated with some of the earliest copper production in Southwest Asia, archaeologists have long puzzled over slag that seems both promising and frustratingly opaque. Some pieces contain clear traces of copper, others none at all. Some preserve minerals tied to arsenic, while others seem strangely drained of them.

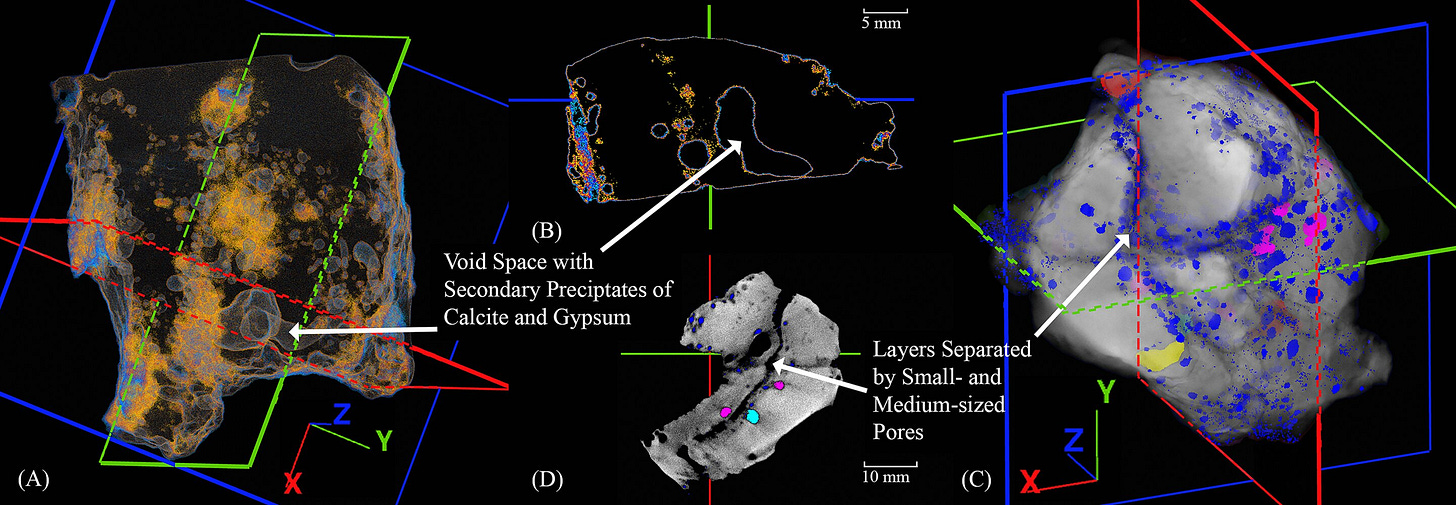

A new study1 led by Benjamin Sabatini and Antoine Allanore introduces an unexpected tool to the challenge. Using high-resolution industrial CT scanners, the team examined 5,000-year-old slag with the same technology that modern medicine uses to peer inside the human body. Rather than bones and organs, they sought droplets of copper, mineral inclusions, tunnels carved by escaping gas, and the quiet internal geometry of the waste left behind by some of the world’s earliest metalworkers.

The result is less a technological breakthrough than a conceptual shift. CT scanning allows ancient slag to be treated not as debris but as a three-dimensional archive.

“The slag is not simply residue. It is the diary of a technological process, written in minerals instead of ink,” says Dr. Elena Rossi, a materials archaeologist at Cambridge University.

The diary, as it turns out, is surprisingly rich.