In a Sacred Cave, Traces of a Distant Homeland

On the northern shore of Guam, inside a beachside cave shaped by salt and wind, researchers have found evidence of one of the oldest rice traditions in the Pacific. But this was no granary. The charred husks of domesticated rice, lodged into pottery shards and buried in sediment, suggest something more symbolic. They tell a story not just of cultivation, but of memory, meaning, and the ritual heartbeat of an ancient voyage.

According to a new study published in Science Advances1, this discovery at Ritidian Beach Cave marks the earliest known presence of rice in Remote Oceania. The findings push back the timeline of rice in the region by millennia and settle long-standing questions about the cultural baggage brought by the first people to settle the Mariana Islands over 3,000 years ago.

"This study provides strong evidence that the first long-distance ocean crossings into the Pacific were not accidental," said archaeologist Mike Carson. "These early seafarers brought rice with them deliberately—as a vital part of their cultural identity."

Across the Ocean with Rice

The story begins more than 3,500 years ago, when the ancestors of today’s Chamorro people set sail from the northern Philippines. They crossed at least 2,300 kilometers of open Pacific Ocean—an extraordinary act of navigation and planning, without maps or compasses.

Archaeological, genetic, and linguistic evidence already confirmed these early islanders had roots in Southeast Asia, and ultimately Taiwan. But how they fed themselves during the journey, and what foods they intended to grow or carry for ritual use, remained unclear.

Rice, domesticated in China around 9,000 years ago, had long been part of Austronesian foodways. Its spread into Taiwan and Island Southeast Asia was well documented. Yet until now, direct evidence of its arrival in the Marianas had eluded archaeologists.

Rice in the Shards

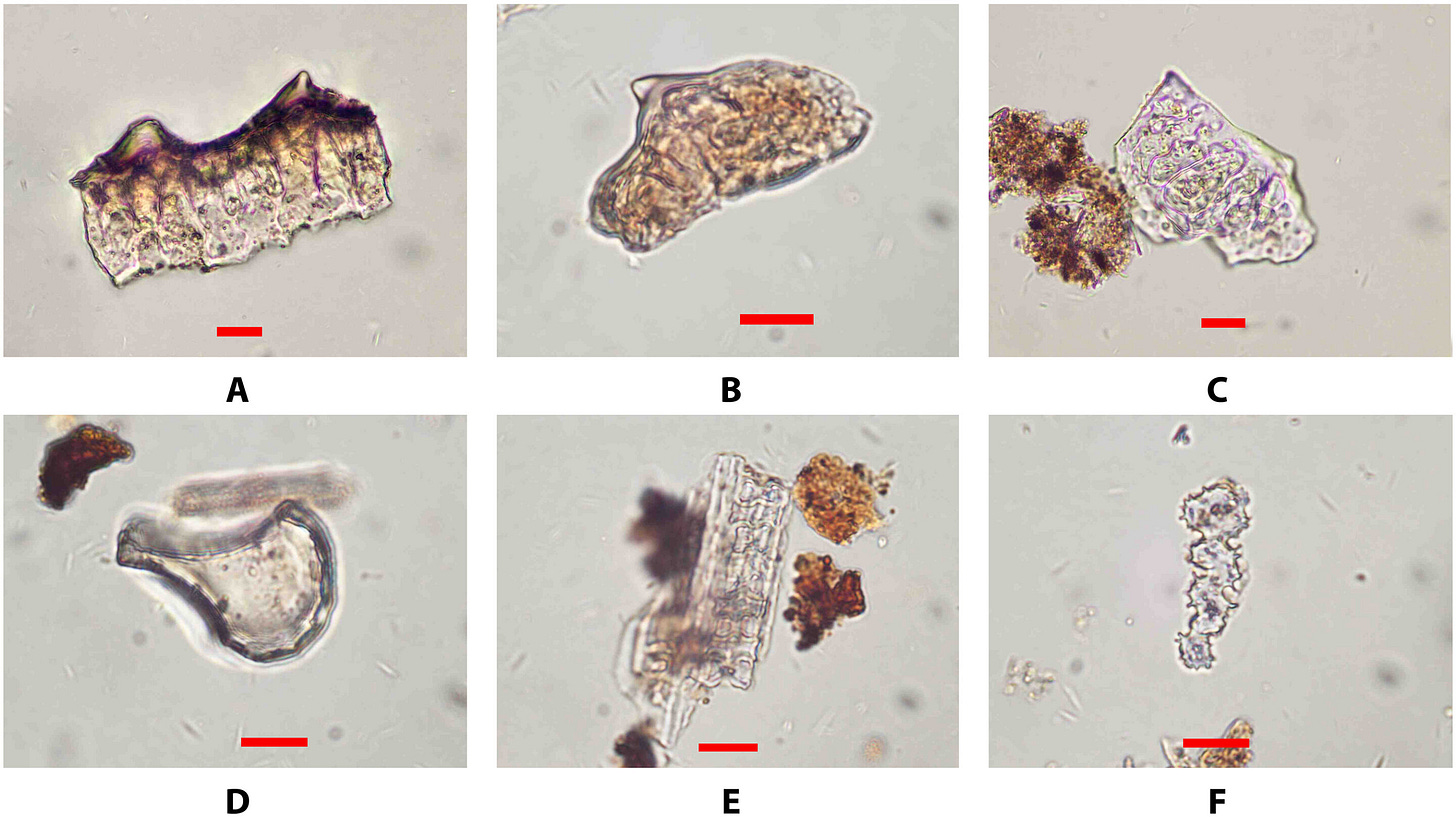

The breakthrough came not from a field or midden, but from a cave. In a small number of pottery fragments from Ritidian Beach Cave, researchers found silica structures known as phytoliths—microscopic plant residues that can survive long after a plant decays. Among them were clear indicators of domesticated Oryza sativa.

But phytoliths alone aren’t always definitive. To confirm the identification, the team used high-powered microscopy to analyze the morphology of husk impressions preserved in the clay surface of the pots. Crucially, the rice husks were not used to temper the pottery—a technique that can complicate interpretation. Instead, the husks were residues from a separate activity, likely involving cooked or processed rice inside the vessel.

The context of the cave—recognized in Chamorro oral tradition as a sacred place—suggests the bowls and the rice were not used for everyday meals. They may have played a role in ceremonial or ritual activities.

"Rice consumption in early Guam seems to have been restricted, symbolic, and tied to life-cycle events or spiritual practice," Carson noted.

More Than a Staple

Rice today is often seen as a food of abundance. But in early Guam, it was likely precious. Spanish records from the 16th century describe rice as rare, cultivated only in small quantities and reserved for death rites or exceptional moments.

That tradition may stretch back to the island’s founding settlers. The rice fragments from Ritidian suggest that even if rice wasn’t grown at scale, it was present—and valued.

Whether rice farming took hold in the islands immediately or centuries later remains uncertain. The cave evidence shows presence, not production. But its early appearance in such a symbolic context points to rice not as a crop of necessity, but as a vessel of identity.

"They didn’t just bring food—they brought meaning," said co-author Hung Hsiao-chun. "Rice may have been more about connection to homeland than nutrition."

Navigators, Not Castaways

The larger implication of the study lies in its affirmation of intentionality. For decades, scholars debated whether early Pacific islanders drifted into Remote Oceania by accident. The presence of domesticated rice—difficult to grow, not native to the region, and reserved for ritual—strongly suggests otherwise.

These voyagers didn’t just survive a journey across vast seas. They prepared for it. They curated their tools, seeds, and stories. They carried not only what they needed to eat, but what they needed to remember.

"One of the most extraordinary human voyages began with both survival gear and spiritual cargo," Carson reflected. "Rice was part of both."

Additional Related Research

Carson, M. T., et al. (2020). First settlement of Remote Oceania: Archaeological evidence and recent perspectives. Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, 15(2), 232–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2020.1741739

Bellwood, P. (2017). First Islanders: Prehistory and Human Migration in Island Southeast Asia. Wiley Blackwell.

Hung, H.-C., et al. (2011). The first settlers of Remote Oceania: Evidence from archaeological and linguistic sources. Science, 333(6047), 1624–1627. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1208135

Denham, T. (2011). Early agriculture and plant domestication in New Guinea and Island Southeast Asia. Current Anthropology, 52(S4), S379–S395. https://doi.org/10.1086/659998

Carson, M. T., et al. (2025). Earliest evidence of rice cultivation in Remote Oceania: Ritual use by the first islanders in the Marianas 3500 years ago. Science Advances, 11(26), eadw3591. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adw3591

Carson, M. T., Wang, W., Huan, X., Dong, S., Hung, H.-C., & Deng, Z. (2025). Earliest evidence of rice cultivation in Remote Oceania: Ritual use by the first islanders in the Marianas 3500 years ago. Science Advances, 11(26), eadw3591. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adw3591