Carving a Passage Through Time

Some 30,000 years ago, a band of early modern humans stood on the rocky coast of what is now northern Taiwan and stared into a horizon without maps. What lay ahead was no calm lagoon but the Kuroshio Current, one of the strongest ocean flows on Earth. On the far side, hidden beyond 225 kilometers of open sea, were the Ryukyu Islands—including Yonaguni and Okinawa. And somehow, those Paleolithic pioneers made it across.

How?

That question has challenged archaeologists and oceanographers alike. Fossils and stone tools place humans on those islands during the Upper Paleolithic, but little was known about how they arrived. Two recent1 studies2 led by Professor Yousuke Kaifu of the University of Tokyo have changed that, combining simulation and experimental archaeology to explore the plausibility of a long-distance sea crossing in a dugout canoe.

A Canoe Called Sugime

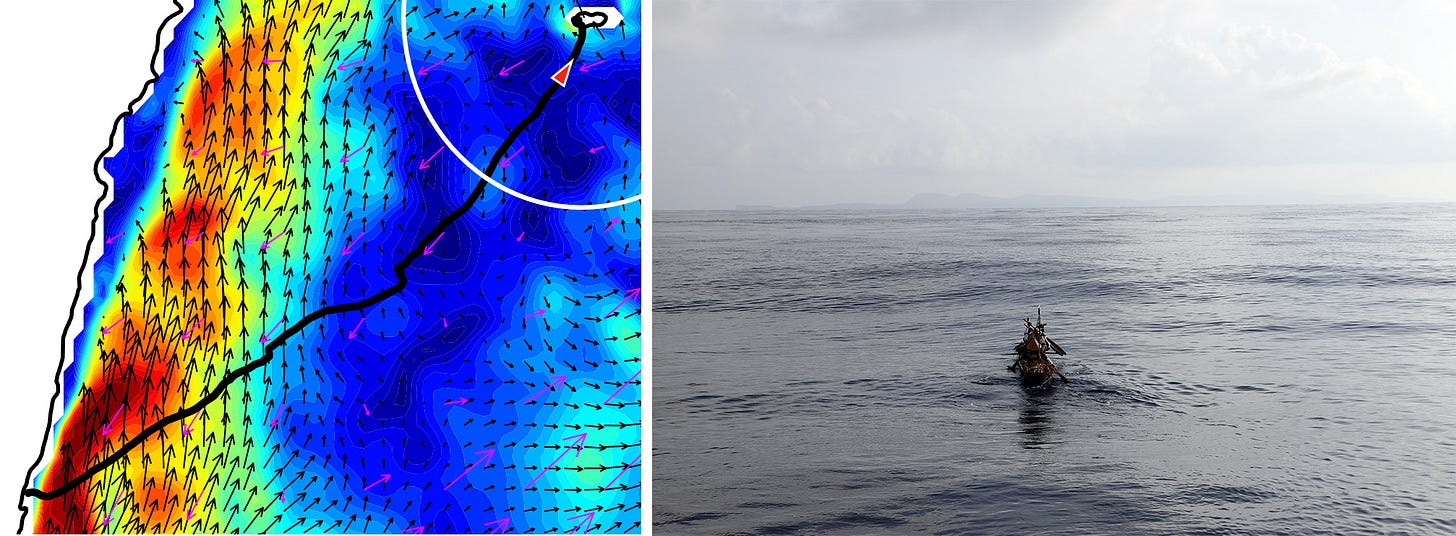

In 2019, Kaifu's team constructed a 7.5-meter dugout canoe using replicas of Paleolithic stone tools and a single Japanese cedar. The result, named Sugime, wasn’t a modern watercraft. It was slow, heavy, and rudimentary by today's standards—yet it proved to be seaworthy enough to attempt the crossing.

Navigating by sun, stars, swells, and instinct alone, the crew paddled Sugime 225 kilometers from Taiwan to Yonaguni in 45 hours. For most of that journey, they had no visual contact with land.

"Those male and female pioneers must have all been experienced paddlers with effective strategies and a strong will to explore the unknown," Kaifu said.

Testing the Current

A one-off voyage can offer clues, but it cannot answer all the questions. So the team also turned to ocean modeling. Led by Yu-Lin Chang, an oceanographer with the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, the team ran hundreds of simulations under varying ancient and modern sea conditions.

"The Kuroshio is usually considered a death sentence to early boats," Chang noted. "But with the right strategy, the results were far more promising than expected."

The key was launching from northern Taiwan and paddling southeast—not straight toward the destination. This trajectory allowed early navigators to counter the current's flow and use its energy rather than be swept away by it.

No Return Ticket

The simulations and voyage both suggest that this was not a casual fishing trip. Those who made the crossing likely had no expectation of returning. There were no maps, no recorded charts, and no back-up plan.

"If you have a map and understand the Kuroshio, maybe you can go back. But Paleolithic people likely couldn’t," said Kaifu. "This was a one-way leap into the unknown."

That leap, however, was calculated. Early seafarers seem to have understood wave patterns, wind, stellar navigation, and how to read the ocean's subtle signs. The skills bear a resemblance to what is seen in later Pacific voyaging cultures like the Polynesians, though separated by tens of thousands of years.

Experimental Archaeology with a Pulse

The Sugime expedition is more than a reenactment; it's a methodological bridge between the abstract past and material possibility. The canoe’s construction process was just as important as the journey itself. It required over 50 days of labor using stone adzes and chisels, revealing the tremendous investment such a voyage demanded.

The project adds momentum to a growing body of research challenging long-held views of early humans as primarily terrestrial. Increasingly, evidence supports the idea that coastal and marine pathways were as vital as land corridors during human dispersals.

From Taiwan to the World

This research doesn’t just illuminate migration into the Ryukyus. It reshapes broader theories of early migration into the Japanese archipelago and island Southeast Asia. Previous assumptions held that open-ocean crossings were unlikely without advanced boats. But the Sugime test suggests otherwise: with stone tools, cedar trees, and a deep understanding of sea behavior, humans could cross even the most forbidding waters.

"Our Paleolithic ancestors were not simply drifting on currents," Kaifu emphasized. "They were taking strategic risks to advance their reach."

Related Research and Comparative Studies

Chang, Y.-L. K., et al. (2025). Traversing the Kuroshio: Paleolithic migration across one of the world’s strongest ocean currents. Science Advances, 11(26). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adv5508

Kaifu, Y., et al. (2025). Paleolithic seafaring in East Asia: An experimental test of the dugout canoe hypothesis. Science Advances, 11(26). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adv5507

Anderson, A. (2010). The First Migration: Oceanic Settlement and Polynesian Voyaging. University of Hawai‘i Press.

Erlandson, J. M. (2007). Seafaring before the Neolithic: Testing the coastal migration hypothesis. In Human Migration: A Genetic, Archaeological and Anthropological Perspective (pp. 59-75).

Fujita, M., et al. (2016). Paleolithic to Neolithic transition in the Japanese Archipelago: New insights from shell midden and submerged site research. Quaternary International, 416, 157-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.059

Chang, Y.-L. K., Miyazawa, Y., Guo, X., Varlamov, S., Yang, H., & Kaifu, Y. (2025). Traversing the Kuroshio: Paleolithic migration across one of the world’s strongest ocean currents. Science Advances, 11(26). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adv5508

Kaifu, Y., Lin, C.-H., Ikeya, N., Yamada, M., Iwase, A., Chang, Y.-L. K., Uchida, M., Hara, K., Amemiya, K., Sung, Y., Suzuki, K., Muramatsu, M., Tanaka, M., Hanai, S., Hawira, T., Uchida, S., Fujita, M., Miyazawa, Y., Nakamura, K., … Goto, A. (2025). Paleolithic seafaring in East Asia: An experimental test of the dugout canoe hypothesis. Science Advances, 11(26). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adv5507