A New Lens on an Old Question

For more than a century, linguists have puzzled over the same riddle: if human languages vary so widely, why do certain grammatical structures keep resurfacing in communities separated by oceans, continents, and millennia?

From the ordering of verbs and objects to how languages mark their subjects, researchers have long pointed to recurring patterns as evidence that human cognition nudges languages toward familiar shapes. Yet these so-called universal tendencies have always lived in a statistical fog. Languages are not independent datapoints. They share ancestry, geography, and long histories of borrowing.

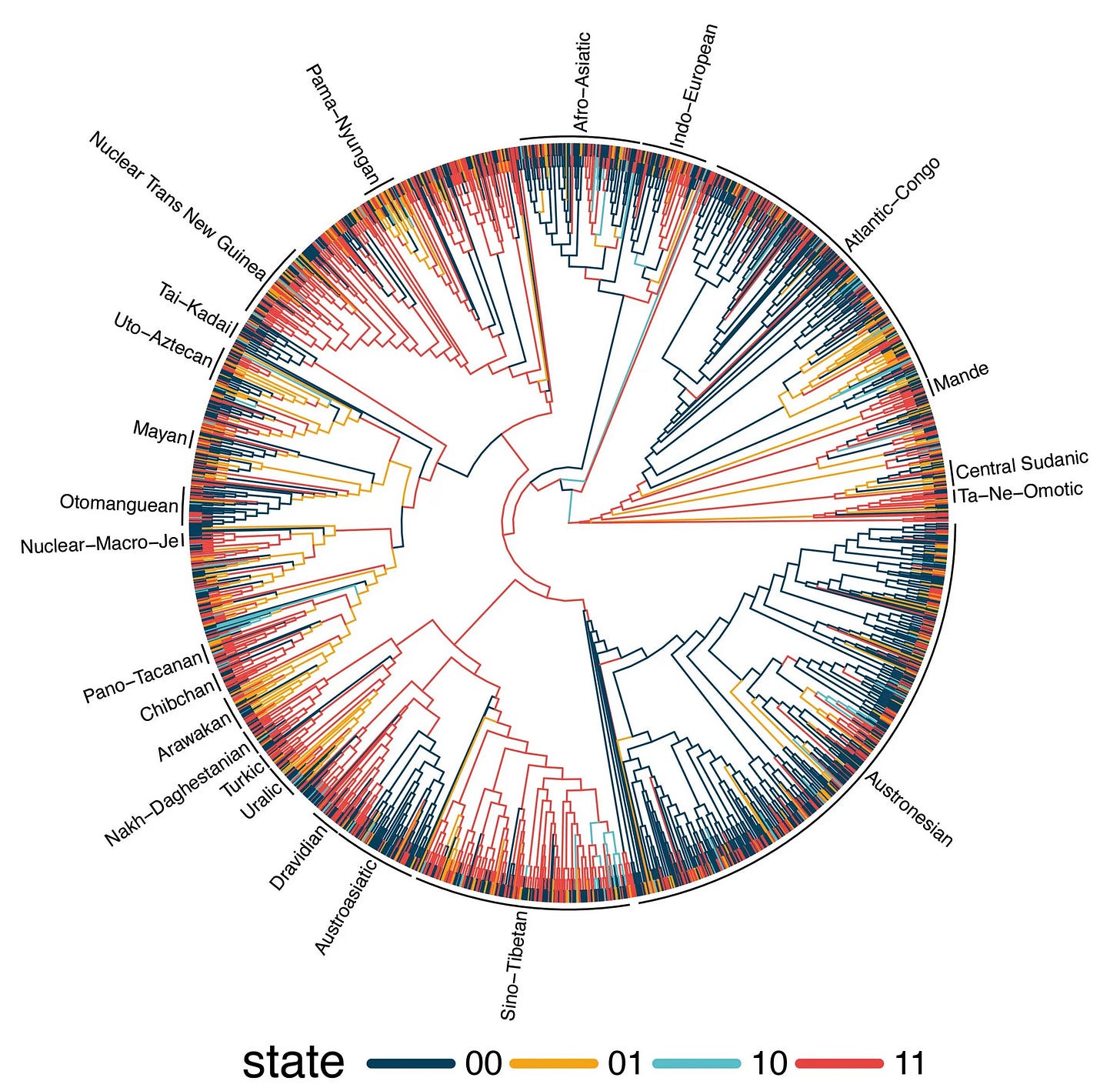

A new study in Nature Human Behaviour1 pushes further into this problem than any previous attempt. Led by Annemarie Verkerk and Russell Gray, the research team used an unusually powerful computational approach to wade through 191 proposed grammatical universals across more than 1,700 languages, drawing on the expansive Grambank database.

The findings add clarity without pretending to offer a final answer. Roughly one-third of the proposed universals show strong statistical support. Another third remain ambiguous. The rest crumble under scrutiny.

As one linguist not involved in the study put it:

“Patterns in language often hide in plain sight, and the real challenge lies in distinguishing what is truly recurrent from what simply survives by chance,”

said Dr. Elena Rossi, a historical linguist at Cambridge University.

The result is a portrait of global linguistic diversity that is neither chaos nor clockwork, but something more nuanced.