For decades, the story of Neanderthal migration into Asia has remained patchy—more shadow than shape. Fossil finds in Siberia and genomic data hinted at a major dispersal from Western to Eastern Eurasia sometime between 120,000 and 60,000 years ago. But how Neanderthals got there, what routes they took, and whether their migration was slow or swift have remained open questions.

Now, a study in PLOS One1 offers a striking hypothesis: Neanderthals may have crossed the 2,000-mile span between the Caucasus Mountains and the Altai region of Siberia in less than two millennia, not through an organized trek, but as an emergent outcome of everyday mobility.

“Neanderthal dispersal into the Altai wasn't the result of deliberate navigation toward a destination,” explained Emily Coco, the study’s lead author. “It was a product of locally informed movements shaped by landscape and climate.”

A Northern Passage through a Patchy Record

The archaeological sites between the western Caucasus and the Altai Mountains are few. Genetic links between Neanderthals in Europe and those excavated in Chagyrskaya Cave suggest at least one major eastward movement. Yet, the archaeological breadcrumbs are too sparse to map out a firm path.

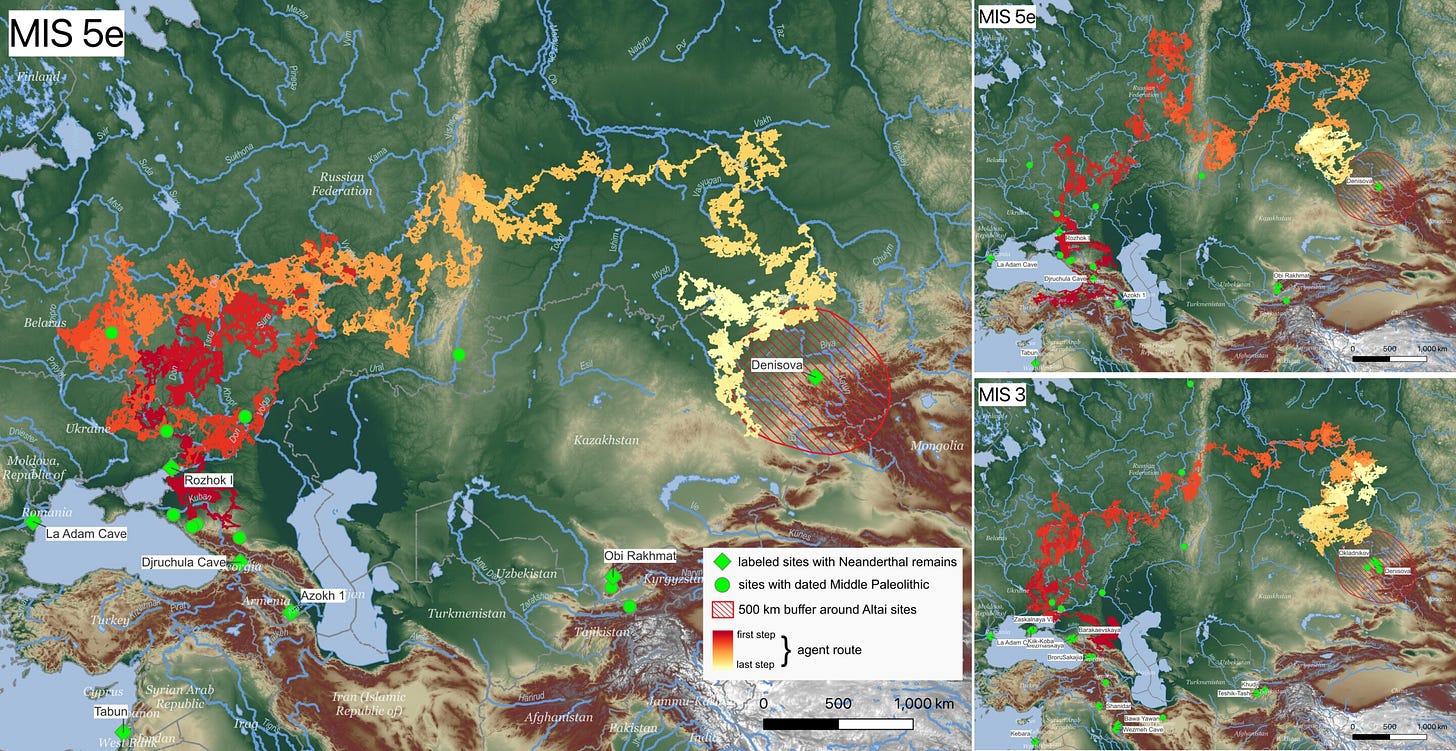

To explore how such a migration might have occurred, Coco and her colleague Radu Iovita turned to agent-based modeling. Instead of assuming that Neanderthals charted optimal or known paths—an unlikely behavior for foragers in unknown terrain—they built a simulation where agents moved across a cost-weighted landscape. This method allowed for random movement choices within the constraints of rivers, mountains, and ice, mirroring how foragers likely navigated in the Pleistocene.

The simulated “agents” were dropped into either the northern or southern Caucasus and allowed to move using what's known as a Lévy walk—favoring short distances with occasional long steps—reflecting the stochastic nature of foraging behavior. If they entered “new territory,” their range expanded, modeling the behavior of early colonizers.

“We wanted to test if a long-distance migration could simply emerge from the ordinary decisions Neanderthals would make based on their local environment,” the authors noted.

River Valleys as Ancient Highways

Out of 110 simulation runs, only three agents reached the Altai Mountains within a range of 500 kilometers. But all three successful migrations took less than 2,000 years—a blink in archaeological time—and followed similar routes.

The common path: a broad northern arc through the Volga and Kama river valleys, across the Urals, and along the Irtysh River into southern Siberia. Rivers—especially those running roughly east-west—functioned as conduits rather than barriers.

“These corridors would have provided reliable water, game, and directionality,” said Iovita. “What we’re seeing is the skeleton of a migration shaped more by rivers than by intentions.”

Interestingly, the agents avoided the southern Caspian corridor, a path previously proposed in earlier models. Transgressions of the Caspian Sea likely rendered that route impassable during glacial periods.

When Climate Opens a Door

The timing of these simulated journeys coincides with two warm periods in the Late Pleistocene: Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5e and MIS 3. Both are marked by interglacial climates, retreating ice, and more hospitable steppe landscapes.

The warm stages offered not just habitable conditions, but geographic connectivity. For instance, during MIS 5e, river valleys were likely more stable, glaciers less extensive, and the terrain easier to traverse.

“Dispersal during warm phases aligns with the environmental tolerances of Neanderthals,” the authors explained. “These weren’t polar pioneers—they followed the seasons.”

Echoes of Interbreeding

The implications go beyond movement. The agents' simulated paths intersected with regions inhabited by Denisovans, another archaic human lineage. Genetic data already suggest Neanderthals and Denisovans interbred multiple times, including in the Altai.

The model lends spatial context to that genomic record: these riverine corridors weren’t just routes of travel—they were zones of contact.

Simulations and the Archaeological Horizon

While the model aligns well with the genetic record and a few archaeological finds, its value lies in hypothesis generation, not confirmation. Many of the modeled migration steps occurred in regions still archaeologically invisible—places where perishable campsites would leave scant trace.

But the simulation does more than suggest a route. It reorients how researchers think about mobility in prehistory. Instead of imagining migrations as linear pilgrimages, the model supports a more diffused process—where large movements are the cumulative product of thousands of local decisions.

“It wasn’t a march,” Coco emphasized. “It was a drift—shaped by rivers, slopes, climate, and chance.”

Related Research and Citations

Skov, L., Peyrégne, S., et al. (2022). Genetic insights into the social organization of Neanderthals. Nature, 610(7932), 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05283-y

Kolobova, K. A., et al. (2020). Archaeological evidence for two separate dispersals of Neanderthals into southern Siberia. PNAS, 117(6), 2879–2885. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1918047117

Ghasidian, E., et al. (2023). Modelling Neanderthals’ dispersal routes from Caucasus towards east. PLOS One, 18(2), e0281978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281978

Slon, V., et al. (2018). The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Nature, 561(7721), 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0455-x

Ruan, J., et al. (2023). Climate shifts orchestrated hominin interbreeding events across Eurasia. Science, 381(6658), 699–704. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.add4459

Coco, E., & Iovita, R. (2025). Agent-based simulations reveal the possibility of multiple rapid northern routes for the second Neanderthal dispersal from Western to Eastern Eurasia. PloS One, 20(6), e0325693. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0325693