A Relationship Older Than History

The story of dogs often begins in the nineteenth century, when kennel clubs codified what counted as a proper pug or a respectable retriever. By that point, the animals had already been sculpted into a sprawling spectrum of forms, from squat companions to lanky hunters. It is tempting to imagine that this creative burst of selective breeding is what gave us the dizzying array of shapes that crowd dog parks today.

But the archaeological record now tells a very different story.

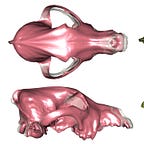

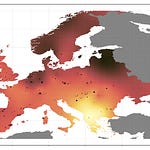

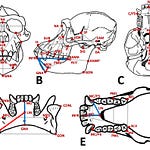

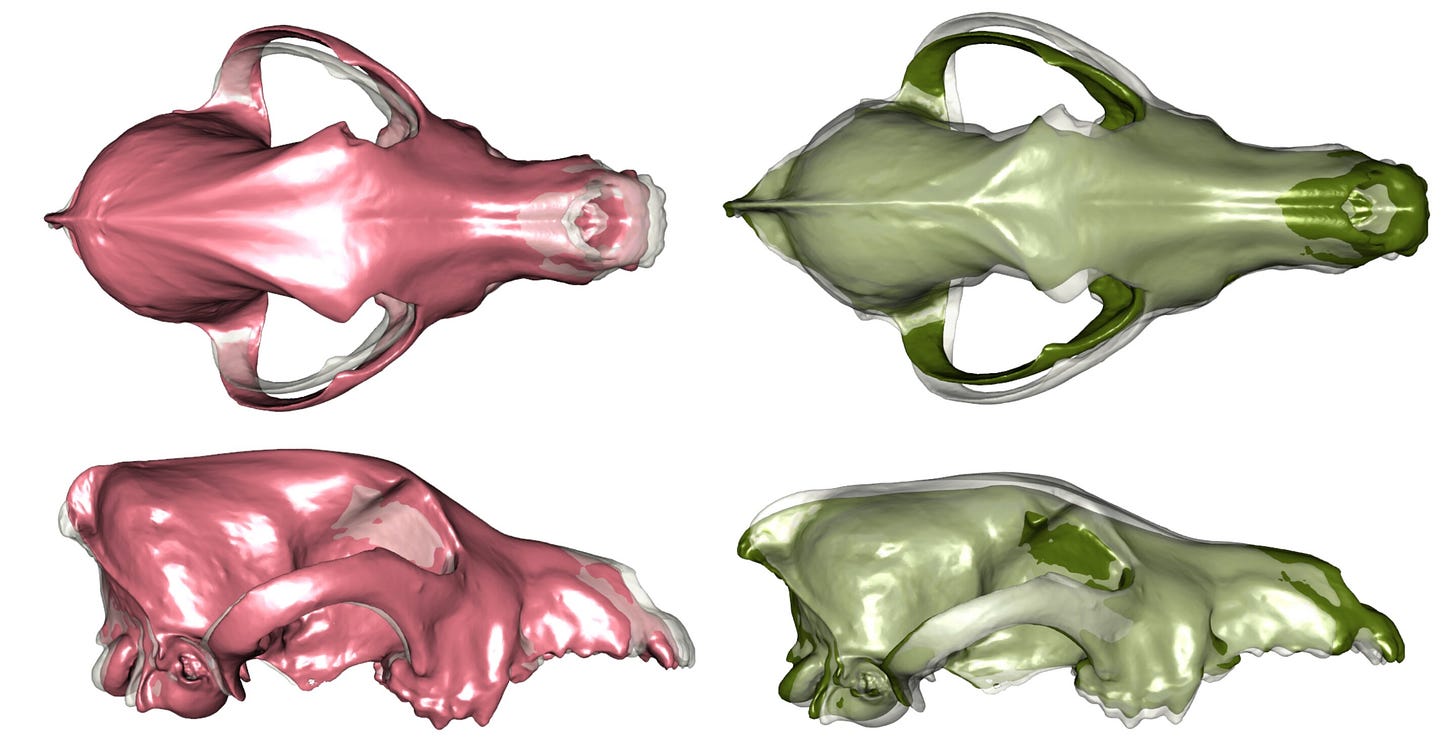

A new international study, drawing on more than half a thousand canid skulls spanning fifty millennia, suggests that much of the diversity we associate with modern dogs had already taken root by the time the earliest farmers were clearing fields and raising sheep. Long before kennel clubs, long before even settled villages, dogs were already experimenting with a startling variety of shapes and sizes.

“The early Holocene was a period of extraordinary morphological freedom for dogs,” says Dr. Elena Rossi, a zooarchaeologist at Cambridge University. “The partnership with humans created ecological niches that wolves could not occupy, and canid forms proliferated as a result.”

The new study, published in Science,1 is the most expansive attempt yet to trace how dogs began diverging from wolves in their bone structure. Its findings suggest that by at least 11,000 years ago, dogs already exhibited roughly half the physical diversity seen today.

The Victorian era, it turns out, added finesse and extremes. But the foundations of dog variety were laid thousands of years earlier.