For centuries, the prehistory of West Africa has lingered in the shadows of better-studied regions. Europe’s caves brim with art and stratigraphy; East Africa’s rift valleys yield hominin fossils and ancient tools. By contrast, West Africa has offered far fewer windows into its past. The climate and geology have conspired to erase many traces of human life, leaving archaeologists with a patchwork record.

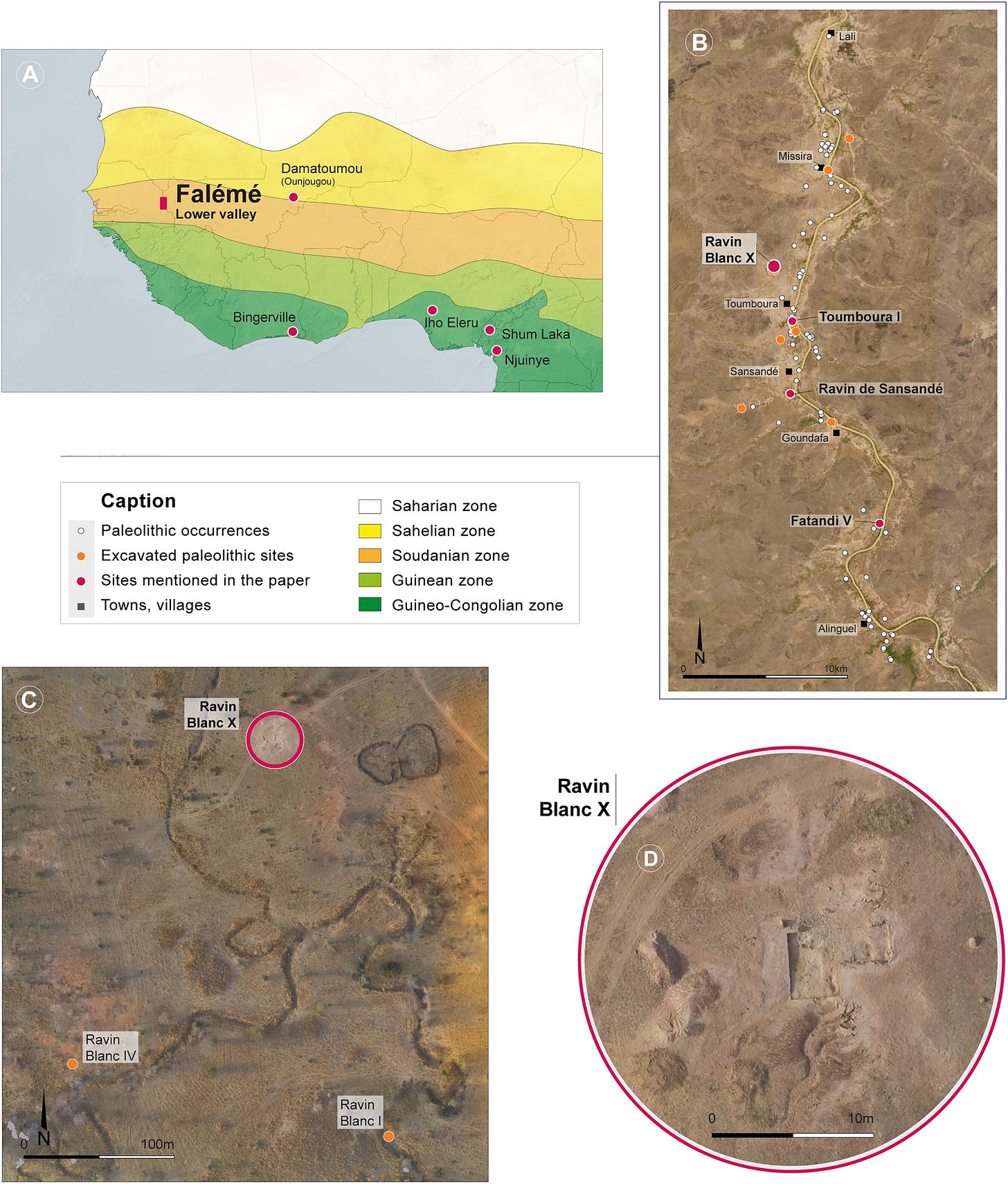

Now, a site1 tucked into Senegal’s Falémé Valley is helping to fill that gap. Excavations at Ravin Blanc X (RBX) have revealed an Early Holocene workshop where hunter-gatherers knapped quartz into tools beside a small fireplace. Radiocarbon dates place this activity around 9,100 years ago. It is one of the rare Later Stone Age (LSA) sites in West Africa preserved with enough clarity to show how stone, fire, and environment intersected in daily life.

“Stratification is crucial: it captures successive phases of occupation and provides key information on chronology, lifestyle changes, and climatic and environmental evolution,” notes Anne Mayor of the University of Geneva, who co-directed the project.

A rare archaeological pocket

The RBX site lies within a ravine whose sediments shielded the remains of an aceramic Later Stone Age occupation. In 2017, surface finds led researchers to test the site. Beneath later Neolithic deposits, they uncovered a layer dense with lithics and charcoal. The heart of this layer contained a fireplace and a knapping floor, intact after nearly 9,000 years.

What the team found was not finished tools but debris. Flakes, cores, and fragments of quartz told the story of toolmaking in action. By refitting broken pieces, archaeologists could reconstruct the reduction sequences. Two main types of blanks were produced: broad, rectilinear flakes and narrower, elongated ones with oblique points. Retouching was rare; precision at the knapping stage meant the tools were already close to final form.

The quartz itself was carefully chosen. Of the valley’s many sources, people selected microcrystalline blocks with predictable fracture patterns, demonstrating a practiced eye for stone quality.

Stones in the savanna

The RBX fireplace offered another glimpse of daily life. Charcoal analysis showed that the wood came from Detarium species, small trees common in dry savannas whose dense wood burns hot. Phytoliths—silica bodies from ancient plants—revealed a landscape of open grasslands dotted with palms and scattered trees. This was the onset of the African Humid Period, when rainfall transformed parts of the Sahel into more fertile terrain.

Together, the evidence situates RBX’s occupants within a dynamic ecological transition. Their tools and fire hint at groups adapted to a savanna that was greener than today, yet still demanding in its seasonal rhythms.

Shared traditions, distinct choices

Comparisons with other sites show that the RBX toolkit was not unique. Technological parallels exist with Fatandi V in Senegal and Damatoumou 1 in Mali, pointing to a Sahelo-Sudanian LSA tradition. Yet contrasts emerge when comparing savanna groups with those in West Africa’s tropical forests. The latter show less standardization and more opportunistic toolmaking.

“The microliths found at these savannah sites reveal sophisticated craftsmanship aimed at producing highly standardized, identical tools,” says Mayor. “Conversely, sites further south, in tropical forest settings, show different, more opportunistic technical choices.”

Such differences suggest that by 9,000 years ago, cultural distinctions were already emerging between communities in contrasting environments.

Why it matters

The Ravin Blanc X site offers more than a single episode of tool production. It demonstrates that well-preserved LSA contexts in West Africa can exist and can illuminate cultural diversity at a critical juncture: the transition from foraging lifeways to the first ceramics, domestication, and Neolithic societies.

By anchoring chronology with radiocarbon dates, RBX bridges the gap between the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene in a region where timelines have remained hazy. It underscores that the history of human ingenuity is not confined to Europe’s caves or Africa’s rift valleys. The people of the Falémé Valley were equally skilled at shaping stone and navigating changing landscapes.

Related Research

Sorbini, G., et al. (2023). “Technological diversity in the Later Stone Age of West Africa.” African Archaeological Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-023-09568-0

Huysecom, E., et al. (2012). “The emergence of pottery in Africa during the tenth millennium cal BP.” Journal of African Archaeology, 10(1): 43–65. https://doi.org/10.3213/2191-5784-10210

Scerri, E. M. L., et al. (2016). “The West African Stone Age in the context of African prehistory.” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 51(4): 507–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2016.1261741

Lespez, L., et al. (2020). “Palaeoenvironments of the Falémé Valley (Senegal) and their impact on human settlement.” Quaternary International, 554: 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.06.017

Pruvost, C., Huysecom, E., Garnier, A., Hajdas, I., Höhn, A., Lespez, L., Rasse, M., Douze, K., Soriano, S., Fichet, V., Saulnier-Copard, S., Ndiaye, M., & Mayor, A. (2025). A Later Stone Age quartz knapping workshop and fireplace dated to the Early Holocene in Senegal: The Ravin Blanc X site (RBX). PloS One, 20(9), e0329824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0329824