In the foothills of the Caucasus, archaeologists have recovered something unusual1 from Dzudzuana Cave: tiny traces of indigotin, the molecule that produces indigo blue. The residues clung to pebbles used as grinding tools 34,000 years ago. They came not from food, but from the leaves of Isatis tinctoria L.—a plant better known as woad.

This is the first evidence that Upper Paleolithic groups intentionally processed a non-nutritional plant to extract compounds for purposes beyond survival. For archaeologists, it is a rare window into how Homo sapiens looked to plants not just for calories, but for color, healing, and meaning.

“Rather than viewing plants solely as food resources, this study highlights their role in complex operations, likely involving the transformation of perishable materials for use in different phases of daily life,” noted archaeologist Laura Longo of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, who led the research.

A cave, some pebbles, and unexpected color

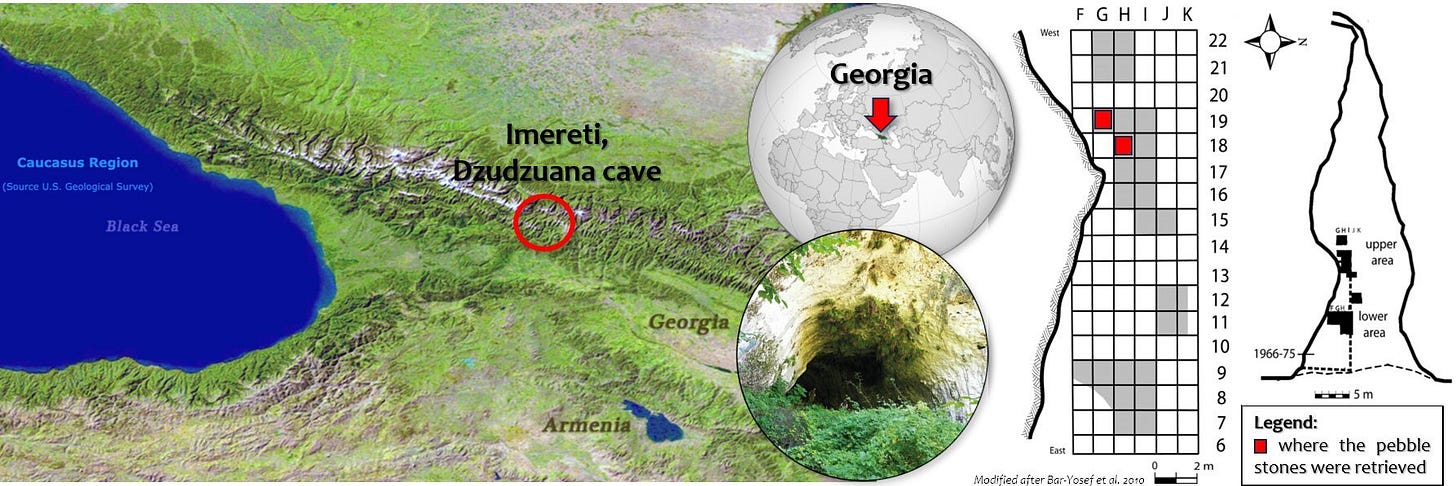

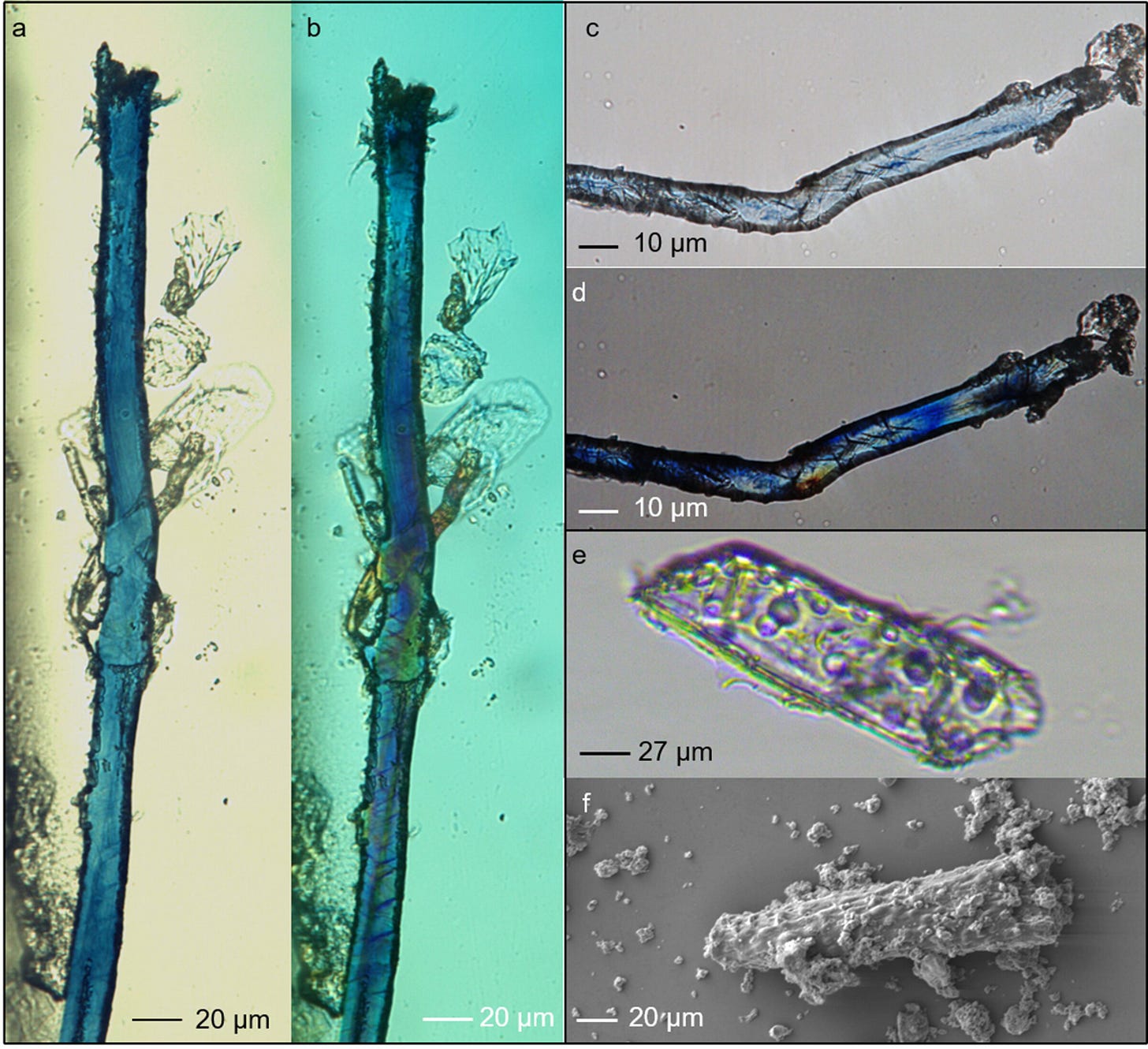

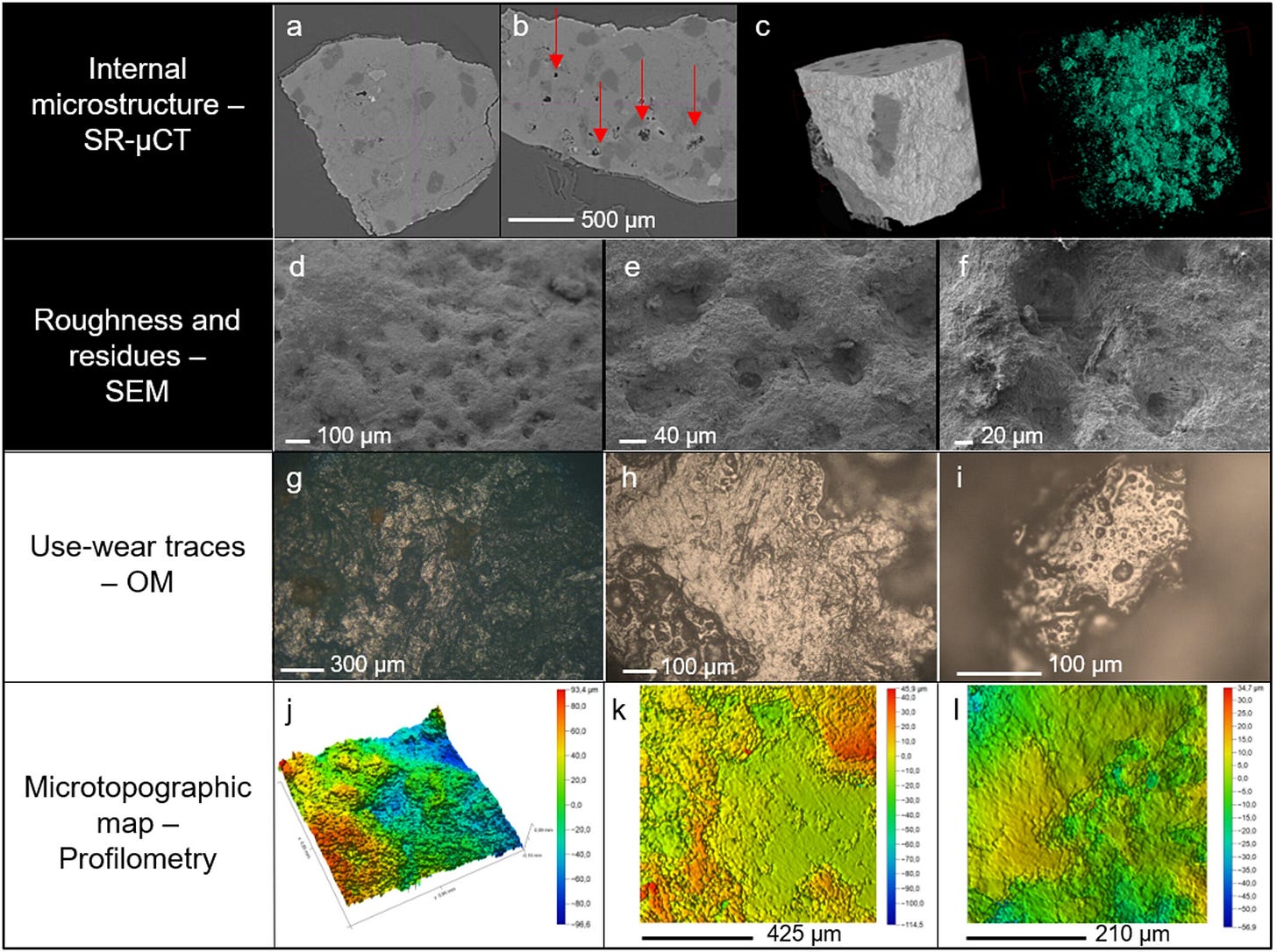

Dzudzuana Cave, tucked into the Georgian Caucasus, has long yielded evidence of early modern human life. Excavations in the early 2000s recovered unknapped stone pebbles that had been used for grinding. Initially, the goal was to identify what these tools processed. Microscopic and chemical analysis revealed starch grains and wear consistent with soft plant material. Then came a surprise: blue residues concentrated in the worn zones.

Advanced spectroscopy confirmed that the pigment was indigotin. The chemical forms when oxygen reacts with glycoside precursors in woad leaves during crushing. This means Paleolithic groups intentionally processed the plant, though its leaves have no nutritional value.

Woad in the Paleolithic imagination

The question is why. Isatis tinctoria has a deep history as both a dye and a medicinal plant. Medieval Europeans used it to produce blue textiles, while traditional remedies valued it for anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties.

At Dzudzuana, the blue residues hint at similar possibilities. The pigments may have been used to color fibers, skins, or bodies. They may also have been part of medicinal or ritual practices, with color serving as a marker of power or protection.

What matters most is the evidence of choice. These humans invested time and effort into transforming plants for purposes that reached beyond nutrition.

Experiments in replication

To test the idea, Longo’s team ran replicative experiments. They gathered river pebbles near the cave, cultivated woad, and crushed the leaves. The resulting residues matched the archaeological samples: faint blue fibers clinging to pores in the stone. The work showed that the Paleolithic pebbles could have trapped and preserved pigment for tens of thousands of years.

“Our multi-analytical approach opens new perspectives on the technological and cultural sophistication of Upper Paleolithic populations, who skillfully exploited the inexhaustible resource of plants,” Longo explained.

A glimpse of complex behavior

These findings broaden the picture of Paleolithic ingenuity. Humans at Dzudzuana were not just hunters or gatherers of staples. They were chemists of the forest, experimenting with plants whose properties spoke to senses, bodies, and perhaps spirits.

For anthropologists, the residues suggest a cultural world in which plants shaped identities, rituals, and aesthetics. The traces of blue are fragile, but they point to a capacity for abstract thinking, planning, and symbolic action long before agriculture or writing.

Related Research

Hardy, K., Buckley, S., Collins, M. J., Estalrrich, A., Brothwell, D., Copeland, L., García-Tabernero, A., et al. (2012). Neanderthal medics? Evidence for plant-based dietary and medicinal practices. Naturwissenschaften, 99(8), 617–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-012-0942-0

Power, R. C., Salazar-García, D. C., Rubini, M., Darlas, A., Havarti, K., Walker, M., & Henry, A. G. (2018). Dental calculus indicates widespread plant use within the stable isotope ecology of Upper Paleolithic humans. Nature Communications, 9, 5127. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07282-0

Cagnato, C. (2019). Plant dyes in the archaeological record: Their emergence, identification, and implications. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 26(1), 219–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-018-9361-0

Radini, A., Cummings, L. S., Buckley, S., Macchiarola, M., & Hardy, K. (2019). Human use of plants for non-nutritional purposes: Dental calculus evidence from prehistoric Europe. Antiquity, 93(367), 405–420. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.31

Longo, L., Veronese, M., Cagnato, C., Sorrentino, G., Tetruashvili, A., Belfer-Cohen, A., Jakeli, N., Meshveliani, T., Meneghetti, M., Zoleo, A., Marcomini, A., Artioli, G., Badetti, E., & Hardy, K. (2025). Direct evidence for processing Isatis tinctoria L., a non-nutritional plant, 32-34,000 years ago. PloS One, 20(5), e0321262. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0321262