A Tooth with a Story

In 1924, archaeologists working near the southern entrance of Stonehenge uncovered a fragment of a cow’s jaw. For nearly a century, it sat quietly among thousands of other finds, its significance hidden in plain sight. Now, with the aid of high-resolution isotope analysis1, that jaw has given up a remarkable story about life and movement 5,000 years ago.

The cow, or Bos taurus, lived during the earliest phases of Stonehenge’s construction, around 2995 to 2900 BCE. A single molar from that jaw recorded the chemical traces of its diet, movements, and even its physiological state. Researchers have now decoded that record, and in doing so, they have illuminated the human drama behind the construction of Britain’s most famous monument.

“This study has revealed unprecedented details of six months in a cow’s life, providing the first evidence of cattle movement from Wales as well as documenting dietary changes and life events that happened around 5,000 years ago,” said Jane Evans, a geochemist with the British Geological Survey.

The Science Inside a Tooth

Teeth are time capsules. As they grow, their enamel and dentine trap tiny amounts of the elements circulating in an animal’s body. These isotopes—variations of common elements like carbon, oxygen, strontium, and lead—carry the signature of the landscapes and diets the animal experienced.

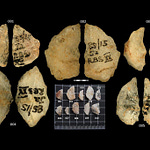

The research team sliced the cow’s third molar into nine layers, each corresponding to a different phase of growth during the animal’s second year of life. By analyzing these layers, they could reconstruct about six months of its existence, spanning a winter-to-summer cycle.

Oxygen isotopes reflected seasonal temperature shifts, confirming that the tooth grew from winter into summer.

Carbon isotopes tracked dietary changes, showing that the cow fed on woodland fodder during the colder months and moved to open pastures in summer.

Strontium isotopes revealed something extraordinary: the geological fingerprint of its diet didn’t match the chalky soils of Salisbury Plain. Instead, it aligned with much older Paleozoic rocks found in southwest Wales—the same region where Stonehenge’s bluestones were quarried.

“It raises the tantalizing possibility that cattle helped to haul the stones,” said Michael Parker Pearson of UCL Archaeology, who has long studied the monument’s origins.

Pregnancy in the Isotope Record

One finding stood out: a spike in lead isotopes during late winter to spring. The signal could not be explained by local geology or fodder alone. Researchers propose that the lead came from the cow’s own bones, released into her bloodstream during a period of stress—possibly pregnancy or nursing.

To test that theory, the team turned to a peptide-based sexing method. The result: a high probability that this animal was female. If the interpretation holds, the isotopic record captures not only her journey but also the physiological demands of reproduction during that trek.

“So often grand narratives dominate research on major archaeological sites,” said Richard Madgwick of Cardiff University. “But this detailed biographical approach on a single animal provides a brand-new facet to the story of Stonehenge.”

From Preseli to Salisbury

The implications go beyond one cow. The discovery confirms what many archaeologists have suspected: that people were moving animals over vast distances in the Neolithic. These were not mere subsistence herds. They were likely part of ceremonial feasts and rituals that bound communities together.

Transporting cattle—and possibly the stones themselves—from the Preseli Hills to Salisbury Plain would have been a monumental undertaking. This cow was probably more than a beast of burden. She was part of the social and symbolic economy of a society constructing its most ambitious monument.

A Single Tooth, a Broader Landscape

What can a tooth tell us? Quite a lot, it turns out. It can trace seasonal migrations, reveal the contours of prehistoric trade, and even hint at the intimate life history of an animal that lived five millennia ago.

As new technologies refine the isotopic lens, more stories like this will emerge. Each one will add texture to the story of Stonehenge—not as an isolated feat of engineering, but as a node in a network of people, animals, and landscapes stitched together across deep time.

Related Research

Madgwick, R., et al. (2019). Feasting and mobility in the British Neolithic: Isotopic evidence from Durrington Walls. Science Advances, 5(3), eaau6079. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau6079

Parker Pearson, M., et al. (2019). Megalith quarries for Stonehenge's bluestones. Antiquity, 93(367), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.111

Viner, S., Evans, J., Albarella, U., & Parker Pearson, M. (2010). Cattle mobility in prehistoric Britain: Strontium isotope analysis of cattle teeth from Durrington Walls. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(11), 2812–2820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2010.06.016

Evans, J. A., & Tatham, S. (2004). Defining Britain’s Neolithic strontium isotope baseline: New data from the chalk regions of southern England. Journal of Archaeological Science, 31(4), 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2003.10.014

Evans, J., Madgwick, R., Pashley, V., Wagner, D., Savickaite, K., Buckley, M., & Pearson, M. P. (2025). Sequential multi-isotope sampling through a Bos taurus tooth from Stonehenge, to assess comparative sources and incorporation times of strontium and lead. Journal of Archaeological Science, 180(106269), 106269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2025.106269