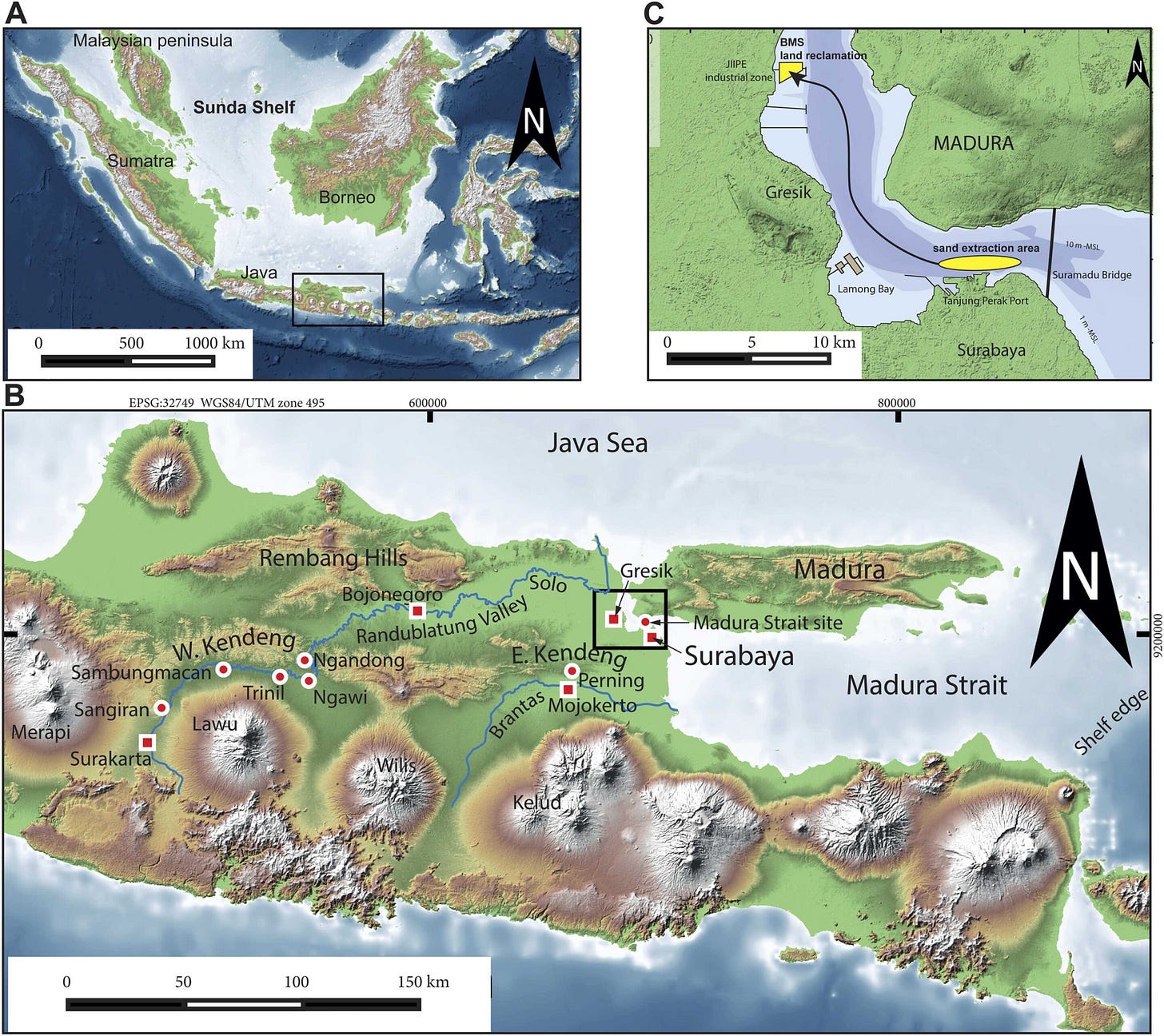

n the Java Sea, beneath the sediment-rich waters of the Madura Strait, archaeologists have found something that rewrites part of the story of human evolution in Southeast Asia. Two fragments of hominin skull—unearthed not by excavation but by industrial dredging for port construction—have offered the first direct fossil evidence of Homo erectus from a region long assumed lost to the sea. The find, announced in Quaternary Environments and Humans1 by Harold Berghuis and colleagues, pushes forward our understanding of hominin range and behavior during the late Middle Pleistocene.

The Madura Strait site lies on the submerged Sunda Shelf, a now-drowned landmass that once connected modern-day Indonesia to mainland Southeast Asia. During glacial periods, sea levels dropped dramatically, exposing vast plains. These corridors, scientists believe, played a critical role in the dispersal of ancient human relatives. But until now, the shelf's fossil record remained inaccessible—lost beneath tens of meters of seawater.

In 2015, a port development company dredged millions of cubic meters of sand from the seafloor to build an artificial island off the coast of Java. Later surveys of the fill material uncovered a trove of vertebrate fossils—over 6,000 specimens, including Stegodon, Duboisia, and water buffalo ancestors. But the most unexpected discoveries were two cranial fragments, designated Madura Strait 1 (MS1) and Madura Strait 2 (MS2), recognized as hominin.

A Window into MIS6

Geological studies and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating placed the fossil-bearing sediments within the Marine Isotope Stage 6 (MIS6), a cold and dry glacial period dating between 191,000 and 130,000 years ago. The preserved river valley, a paleo-channel of the Solo River system, had filled with fluvial sand and gravels before being submerged during the subsequent interglacial.

MS1, a fragment of frontal bone, carries features consistent with late Homo erectus from Java: a prominent supraorbital torus, weak postorbital constriction, and a flattened brow. Metric comparisons with fossils from Ngandong and Sambungmacan—sites along the Solo River known for producing late-surviving Homo erectus—suggest that MS1 fits within this lineage. MS2, a parietal fragment, is less diagnostic but appears morphologically archaic.

"MS1 exhibits characteristic features of the late Javanese Homo erectus, including a flat supratoral plane and a weak postorbital constriction," the authors write. "It is most similar to the Sambungmacan crania, though slightly thinner in torus thickness."

This identification extends the known geographic range of Homo erectus eastward onto what would have been dry lowland plains during the Pleistocene—a reminder that our maps of early human habitats remain partial reconstructions.

Submerged Histories

These fossils challenge long-standing assumptions that Java's Homo erectus populations were geographically isolated. While debates have swirled over the reasons for their prolonged survival—some suggesting ecological refugia or limited competition—the Madura Strait remains point to a broader distribution and a more dynamic picture of hominin movement across Sundaland.

"The Madura Strait skull fragments show that the MIS6 Homo erectus we know from Java also dispersed over the surrounding lowland plains, possibly following the course of the Solo," Berghuis and colleagues argue.

The implications extend beyond just one species. Genetic evidence suggests that Denisovans—a sister lineage to Neanderthals—once lived in parts of Southeast Asia. Yet fossils remain elusive. Submerged valleys like the one in the Madura Strait may hold those answers, though accessing them requires extraordinary circumstances.

"Extracting seabed sand is very expensive. You will only get this done for construction work. So, the only thing we can do is keep in good contact with the local port authorities and developers," the authors note.

Seafloor Archives

As climate change reshapes coastlines and development expands into new marine zones, paleontologists face both opportunities and ethical challenges. The Sundaland seabed—once a Pleistocene landscape teeming with megafauna and archaic humans—now lies beneath shipping lanes and dredgers.

But every fossil hauled from the deep is a fragment of a deeper past: a child’s brow ridge, a deer’s molar, a bone flake bearing cut marks. Together, they tell a story not of isolated survival but of resilience across a vanished continent.

"The answers may very well be at the bottom of the sea."

Related Research

Kaifu, Y., Aziz, F., Indriati, E., et al. (2008). Cranial morphology of Homo erectus from Sangiran. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 135(4), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20763

Rizal, Y., Westaway, K. E., Zaim, Y., et al. (2020). Last appearance of Homo erectus at Ngandong, Java, 117,000–108,000 years ago. Nature, 577(7792), 381–385. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1863-2

Teixeira, J. C., et al. (2021). Widespread Denisovan ancestry in Island Southeast Asia. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5(5), 612–619. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01475-8

Louys, J., & Turner, A. (2012). Environment, sea level, and hominin dispersal across Sunda and Sahul. Current Anthropology, 53(5), 677–691. https://doi.org/10.1086/667321

Berghuis, H. W. K., Kaifu, Y., Wibowo, U. P., van Kolfschoten, T., Sutisna, I., Noerwidi, S., Adhityatama, S., van den Bergh, G., Pop, E., Suriyanto, R. A., Veldkamp, A., Joordens, J. C. A., & Kurniawan, I. (2025). The late Middle Pleistocene Homo erectus of the Madura Strait, first hominin fossils from submerged Sundaland. Quaternary Environments and Humans, 3(2), 100068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qeh.2025.100068