The Hidden Politics of a Spearpoint

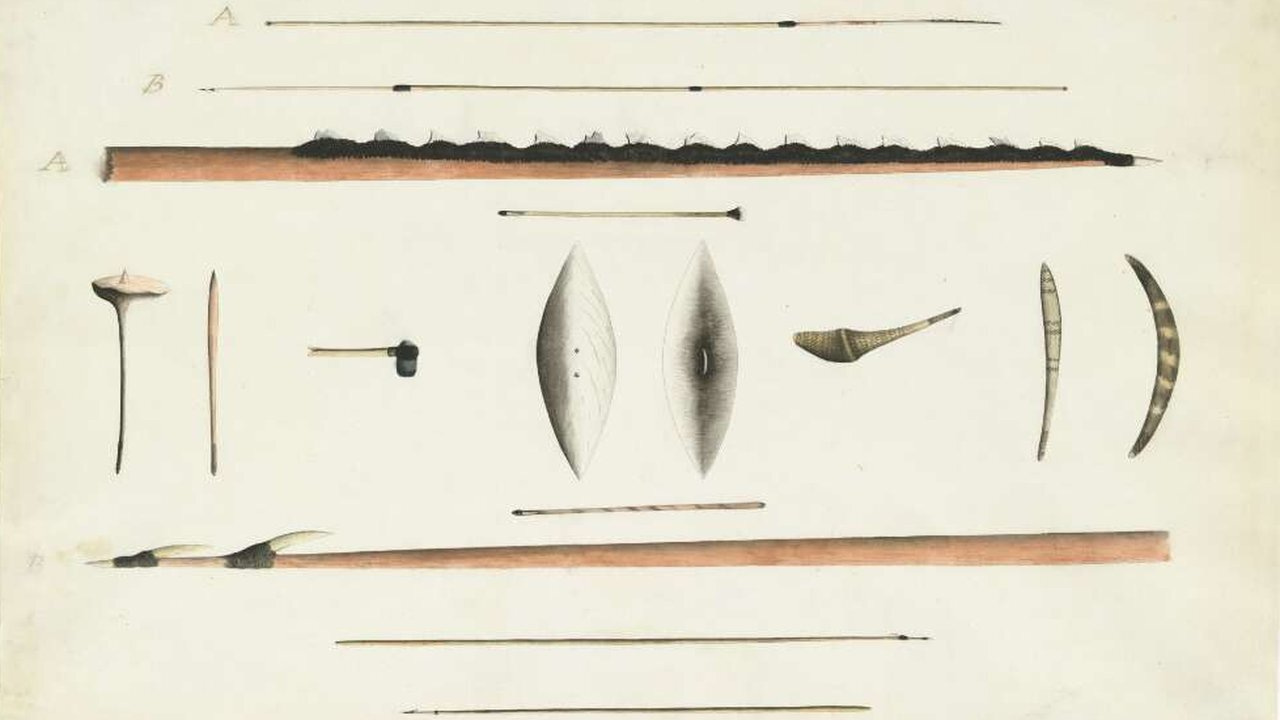

At first glance, a bow or harpoon seems purely practical—a way to get food, fend off predators, or carve a hide. But for anthropologist Marcus Hamilton and his colleagues, these artifacts are something else entirely: political instruments disguised as tools.

Each carries the memory of how a society organized itself to solve problems. A harpoon, with its bone socket, sinew line, and detachable tip, embodies more than mechanical ingenuity. It reflects decisions about labor, knowledge, and risk—about who gets to make, own, and teach technology.

Hamilton’s new study, published in Science Advances1, examines 127 small-scale societies from around the world—hunter-gatherers, horticulturalists, and subsistence farmers—to uncover a universal rule governing how humans build and maintain technological diversity. Whether among Inuit seal hunters, Seri fishers, or Menominee trappers, the same mathematical pattern appears: as societies add new tool parts, their toolkits become richer, but at a slower, sublinear rate. In plain terms, each new part yields diminishing returns.

“Technological systems grow like coral reefs,” says Dr. Rafael Morales, an anthropological theorist at the University of Arizona. “Each new layer adds complexity, but the structure must still support itself. Too much growth without coherence, and it collapses.”