Two Rivers, One Story

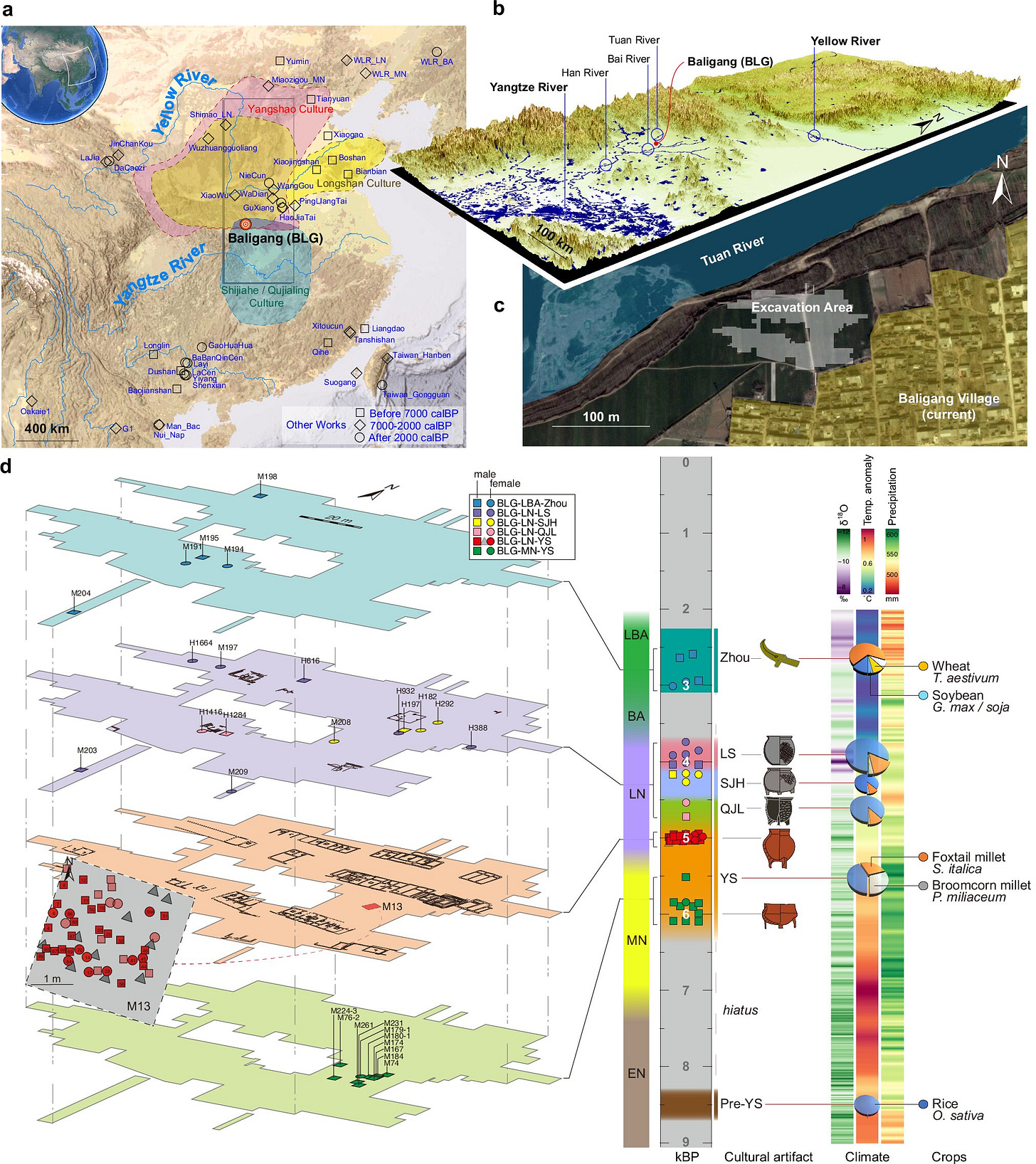

At the dawn of the Neolithic age, the heart of what would become China was divided not by war or politics, but by rivers. To the north flowed the Yellow River, where millet thrived on loess plains. To the south, the Yangtze carved a humid, fertile corridor that gave rise to rice. For decades, archaeologists have known that these two river civilizations didn’t evolve in isolation—they intertwined, traded, and learned from one another. What remained unclear was how deeply their people themselves mingled.

A team of geneticists and archaeologists from Peking University has now filled that gap with evidence written in DNA, extracted from 58 ancient individuals buried at Baligang, a long-inhabited site at the threshold of these two worlds. Their results, published in Nature Communications1 paint a vivid picture of ancient China not as a patchwork of static cultures but as a landscape of movement, mixing, and kinship—culminating in the earliest known example of a patrilineal community in East Asia.

“The Baligang site captures a human experiment in coexistence,” says Dr. Liang Zhu, an archaeogeneticist at Fudan University not involved in the study. “It shows how climate, crops, and kinship braided together to form the social fabric that would eventually shape early Chinese civilization.”