The Bones of a Landscape

From above, the western Andean highlands of northern Chile appear skeletal—long, sun-bleached ridges etched by gullies and dry riverbeds, leading to windswept plateaus where the air thins and the color drains from the land. Yet under this austere surface, archaeologist Adrián Oyaneder has identified traces of human presence that are anything but skeletal. Using high-resolution satellite imagery, he mapped an entire system of ancient hunting structures and small seasonal camps, revealing a landscape that once pulsed with movement, strategy, and life.

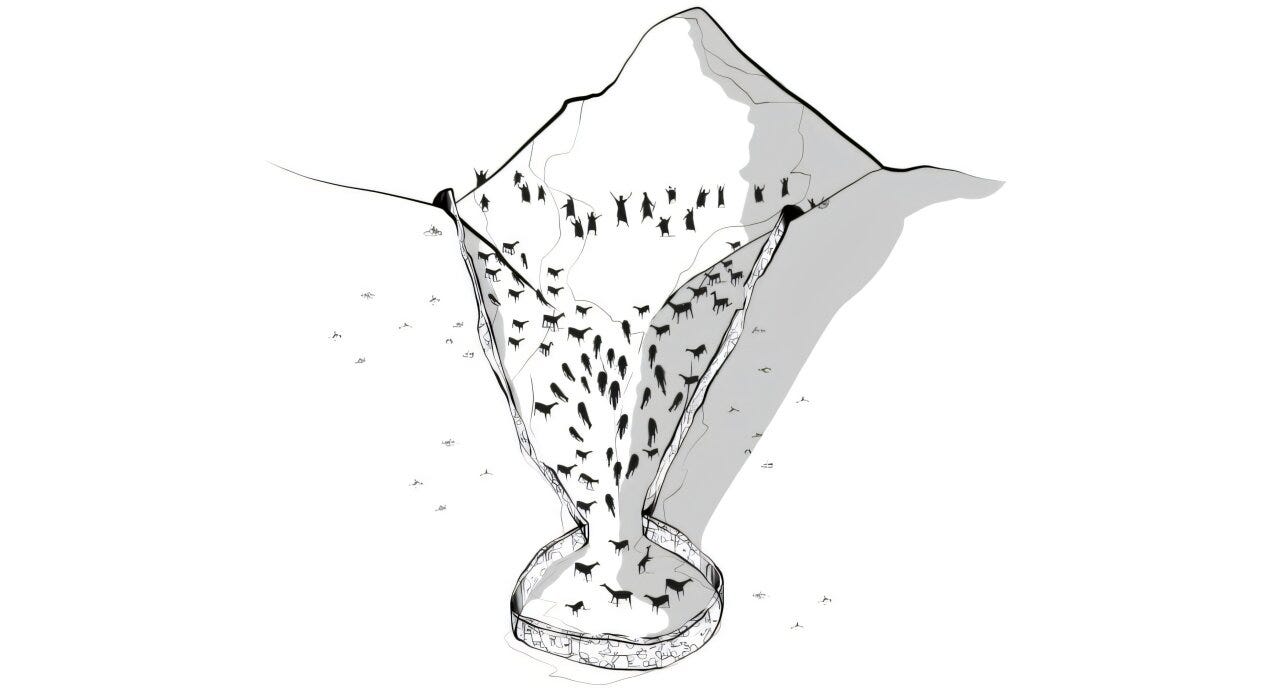

The study, published in Antiquity1 documents 76 large stone hunting traps known as chacus scattered across a 4,600-square-kilometer stretch of the Camarones River Basin in Chile’s Western Valleys. Built from dry-stone walls that stretch for hundreds of meters, these structures once guided herds of wild vicuña—graceful relatives of the alpaca—into enclosures where they could be captured by groups of hunters. Around them, Oyaneder identified nearly 800 small dwellings and outposts that speak to a remarkably durable way of life: one tethered to the rhythms of animal movement and high-altitude ecology rather than to settled fields or permanent villages.

“The spatial regularity of these traps and associated camps suggests not a single episode of use, but a long-term pattern of engagement with the land,” says Dr. Mariana Álvarez, a landscape archaeologist at the University of Buenos Aires. “These were structured environments—maps in stone that organized both animals and people.”