Long before maize fields quilted the Southwest, people were already shaping plant futures in quieter ways. Not by plows or canals, but by pockets, baskets, and grinding stones. One of the most revealing witnesses to this early experiment in cultivation is a small, stubborn tuber with a deep memory: Solanum jamesii, the Four Corners potato.

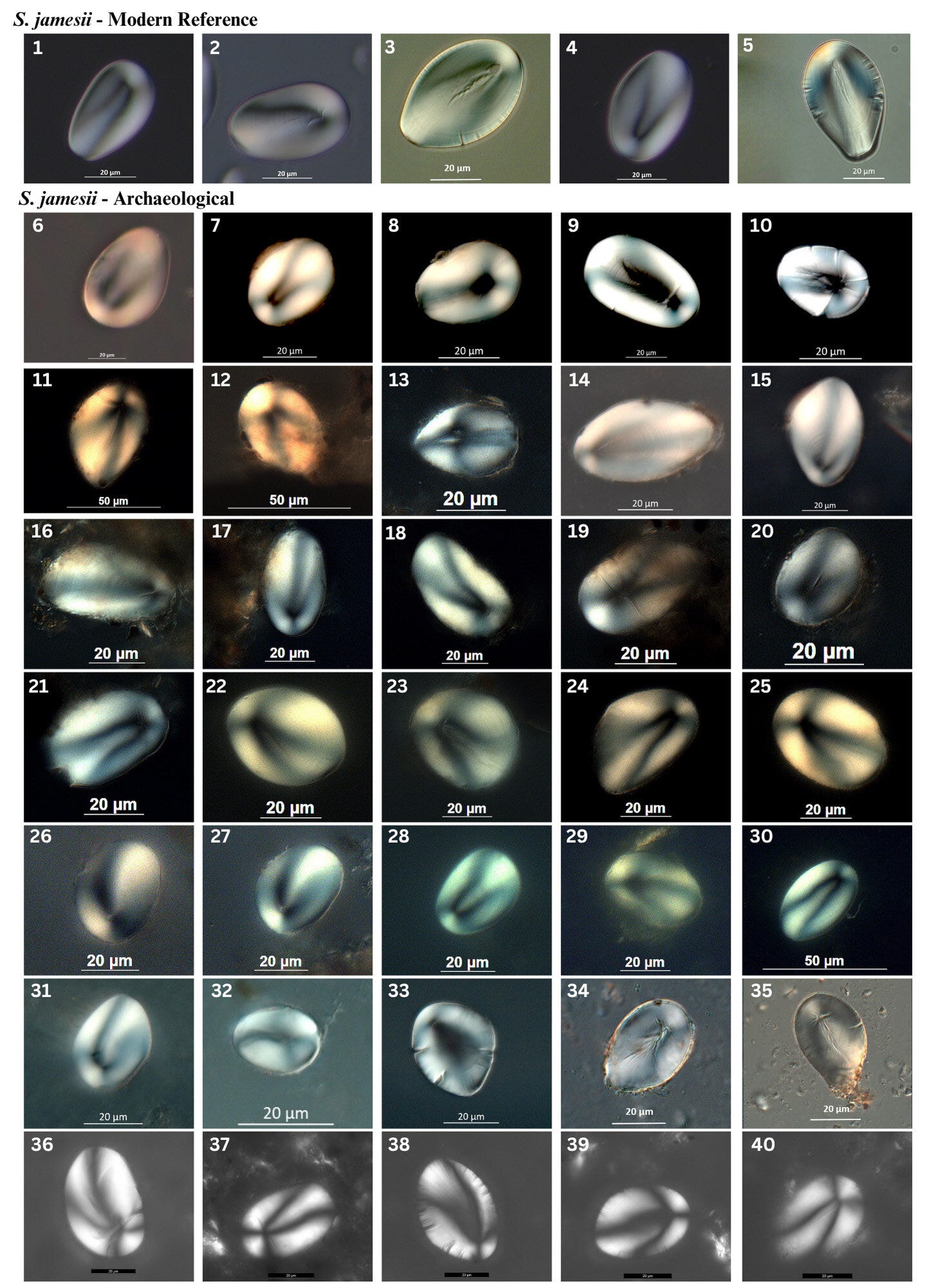

A new study1 led by Lisbeth Louderback and colleagues argues that this wild potato was not just gathered, but deliberately moved, tended, and used for thousands of years. The evidence does not come from fields or seeds, but from starch grains wedged deep inside stone tools. Together, they tell a story of mobility, care, and an Indigenous pathway toward domestication that has long been underestimated.